Often the best way to learn something is the hard way. You tend not to forget when you get bruised in the process.

If that’s the case, then many Cantabrians are gaining memorable lessons about what it is like to live at the sharp end of today’s New Zealand.

I said in my last post that a political tipping point had arrived here in Canterbury with the cancellation of the 2013 Regional Council elections.

If any drop of residual uncertainty remained over that conclusion, the Government – this time in the guise of Education Minister Hekia Parata – evaporated that drop with a high-octane blow-torch that was ‘fit for purpose’.

Announced that day in Lincoln (well away from areas most adversely affected) were proposals that have been described as “sweeping education reforms” that amount to “[t]he dismantling of public education” or, in relation to Intermediate schools, evidence of a “hidden agenda“.

In contrast, Hekia Parata, the Education Minister, described the announcements as “restoring the education sector in greater Christchurch, Selwyn and Waimakariri.”

The Information Sheet detailing the school proposals can be found here.

As ever, there’s a bit of a story behind all of this – and some questions hanging like chads on a Florida ballot paper.

Foremost amongst those hanging questions is that of a certain dog:

Colonel Ross still wore an expression which showed the poor opinion which he had formed of my companion’s ability, but I saw by the Inspector’s face that his attention had been keenly aroused.

“You consider that to be important?” he asked.

“Exceedingly so.”

“Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

“To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

“The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

“That was the curious incident,” remarked Sherlock Holmes.

This is a two part post. The first part deals with the background to the announcements, the reaction to the announcements and the reaction to the reaction. In the second part – following shortly – I’ll focus on the details of the announcements, what I think they mean and ‘the curious incident of the dog that didn’t bark …’.

First, what was the background to these announcements?

Behind the announcements

In September, 2011, then education minister Anne Tolley announced that funding for 167 teacher positions would discontinue at the end of that year:

“Staffing levels directly correlate to student numbers, and the 2012 teacher entitlements will reflect the change in enrolment patterns in the wake of the earthquake.”

She said schools with falling rolls would see a reduction in staffing levels, while schools whose rolls had increased would have extra teachers.

That is, some reductions in resourcing had been signalled to address the so-called ‘over-capacity’ in relation to student rolls. The Government had maintained funding for Christchurch schools whose rolls had reduced after the February, 2011 earthquake but this was to end that same year.

Then, back in May this year, the Government released the document “Directions for Education Renewal in Greater Christchurch”:

The document, which covers the future of education in Christchurch and the Selwyn and Waimakariri districts, proposes investigating the development of education campuses that could include early-childhood education, primary and secondary schools, and tertiary institutions on one site, along with social services.

It “advocates schools sharing facilities such as workshops, gyms, swimming pools, auditoriums, and libraries“, and

Those ideas have been welcomed by principals, but they fear a lack of money could constrain innovation.

There were a few other interesting points made at that time. First, on the money involved:

The document put the cost of repairing 207 earthquake-damaged state schools at $500 million to $750m, and Christchurch’s major public tertiary institutions faced a combined repair cost of about $300m.

The Government would allocate some money to pay for the work, but most of it would be funded through insurance, rationalisation of facilities, using existing reserves, and reprioritising existing budgets.

Over the past ten days, the Government has made much of the $1bn package over the next decade for Christchurch schools but has been coy about just where it would come from, and how much would be new money. There was clearly no such coyness back in May – “most of it would be funded through insurance, rationalisation of facilities, using existing reserves, and reprioritising existing budgets“.

Second, the document “did not provide detail about the future of individual schools“, but,

Those decisions would be made once all the relevant land and population-change information was gathered, Parata said.

Given that some school announcements are only ‘options’ pending geotechnical data (Shirley Boys’, Avonside Girls’) and others have not been announced for the same reason (Redcliffs School and Kaiapoi Borough School), it seems not quite all the “relevant land and population-change information was gathered” prior to the most recent announcements.

Still, best not to quibble – I’m sure a Redcliffs-Sumner Cluster with a single year 1-13 super-site will soon be announced once the goetech data are in for Redcliffs.

Third, the claim was that this was to be driven by Christchurch schools:

Secretary of Education Lesley Longstone said the proposals in the document needed to be led by Christchurch’s education sector and not the ministry.

“We’ve got to do things together.

Encouraging words but, in retrospect, they might be called something else.

Fourth, the costs were clearly going to be crucial:

Canterbury Primary Principals’ Association president John Bangma said the document was exciting, but he was worried the Government would not provide enough money to enable the sector to be as innovative as it could be.

Similarly,

Canterbury-Westland Secondary Principals’ Association chairman Neil Wilkinson said it was an opportunity for education in wider Christchurch, but he was concerned about the fiscal constraints.

Finally, way back in May Bangma had raised concerns over this process being a means of establishing charter schools in Christchurch:

The document did not include any mention of charter schools.

Bangma said he was concerned it was a way of bringing in charter schools by another name, but said he had been assured by Longstone that was not the case.

Now there’s a “curious incident” if ever there was one – but, once again, more on this later.

In August a further version of ‘Directions for Education Renewal‘ was released. In the Introduction (p. 4) it states:

we need to ensure the approach to renewal looks to address inequities and improve outcomes, while prioritising actions that will have a positive impact on learners in greatest need of assistance.

With the costs of renewal considerable, the ideal will be tempered by a sense of what is pragmatic and realistic. Key considerations are the practicalities of existing sites and buildings; the shifts in population distribution and concentration; the development of new communities and a changing urban infrastructure.

Innovative, cost-effective, and sustainable options for organising and funding educational opportunities must be explored to provide for diversity and choice in an economically viable way. There is also a need to align these changes with broader Government policies and commitments for educational achievement.

So, on the one hand, the renewal will “[A]ddress inequities and improve outcomes” and involve “actions that will have a positive impact on learners in greatest need of assistance“. But, on the other, this “ideal” will be “tempered” by the “considerable costs” of renewal. Alignment with “broader Government policies and commitments” is also a must.

As mere words on paper it’s hard definitively to criticise such minimally meaningful phrases. Nevertheless, they do suggest a tension between what the writers believe to be palatable to their audience and what they, in fact, want to implement. To be blunt, there’s enough wiggle room here for a hippopotamus to perform a 180 degree turn.

The document does, however, repeat a significant and now familiar notion (on p. 6) that,

“Recovery” [under the Recovery Strategy produced by CERA] is defined as including both restoration and enhancement within the strategy, which also sees recovery as future focused and taking opportunities for enhancements. Recovery does not mean returning to the state that existed on 3 September 2010.

As with the CCDU’s Central Christchurch Recovery Plan, it’s about ‘enhancement’ as much as – or perhaps more than – it’s about restoration.

But, who gets to say what is ‘enhancing’?

Well, how about ‘the community’? After all, Lesley Longstone has told Christchurch schools (and, presumably, communities) that it’s down to them, not the Ministry.

In fact, the same document summarises the 554 submissions received from the ‘community’ – so what did the summary say?

Apparently,

You want to see diversity in educational options and are open to embracing new and bolder initiatives that will mean greater co-operation and sharing of human and physical resources.

This would mean closer relationships with business and other organisations such as health service providers.

…

You signalled support for ‘shared campuses’ that could provide education from the early years through schooling and into tertiary

…

You emphasised that the learner is the priority and highlighted the importance of listening to what they have to say.

…

You want to continue to have a voice and agree that an education advisory body could provide an opportunity to engage visionary local leaders who can inspire and contribute to the renewal.

…

You also want to continue to be involved and engaged throughout the journey to renewal.

That’s what ‘You’ think, according to the summary. But there were other submitters. Strangely, they were not ‘You’ – only ‘some’.

Some submitters expressed concerns that the vision could be restricted by costs.

Sounds like (almost) everyone was ‘on-board’ with this process – great to see.

The Ministry of Education, then, has simply been ‘channelling’ community desires – a process of consultation and policy implementation you only hear about in utopian novels (or, of course, in many documents from Government departments and ministries).

So, in detail, what was the reaction to this faultless policy process?

Well, considering the above, it was all a bit odd, really.

But, then, here was the process through which principals and teachers were informed. Read it and weep (especially if you were part of the ‘design team’ for the communication process).

The Reaction

The reaction – in Canterbury at least – has been overwhelmingly negative and opposed to the announcements. The Weekend Press editorial (15 September) opened with what should have left every Government MP’s ears ringing painfully with the sound of giant political alarm bells:

The heavy hand of the Government is being felt in Christchurch and citizens are getting alarmed. Days after their voting rights in ECan elections were suspended for years, they were told their schools were to be decimated. The concern and anger are palpable.

The Press is being swamped with letters mostly of complaint, talkback radio is loud with dissent and the Woolston pub and the Fendalton dinner table are no doubt abuzz with the same topic.

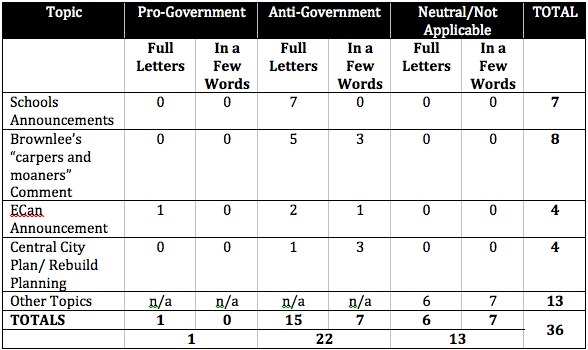

As if the Government’s reputation in Christchurch and Canterbury wasn’t already taking enough of a battering. In that same print edition of The Weekend Press, the following statistics on the full letters and ‘In a few words‘ comments in the same paper are revealing:

That’s not a good scorecard in anyone’s book. It got worse – so far as the schools announcement went – on the Monday: 10 out of 10 full letters were opposed to the announcement.

On Tuesday there were only three letters on the schools announcements but they led the page and all excoriated them. The other letters were on other, local, topics.

On Wednesday an entire page was devoted to letters about the proposals (A7). Of the 13, 11 were damning, 1 was indeterminate and 1 was in support, or at least suggested that any school that didn’t want to close could now be free to apply to become a charter school.

The supporting letter was written by someone from Stoke, in Nelson province. That’s how far the net has to be cast to find some support, it seems.

Then, in the following Weekend Press (22 September) the editorial had these words of warning for the Government:

The mail boxes and email inboxes at The Press have been unusually full in the last week and a half. The Ministry of Education’s and minister Hekia Parata’s proposed changes to the landscape of Canterbury schools has motivated people to write to us in numbers not seen on any issue since the earthquakes.

…

Two features stand out about this week’s mailbag. One is that the ratio of letters against and for the Government’s proposals for schools is running at about 50 to 1. The other is that the writers have written with unusual passion about what schools mean to them and their children, especially in the way that teachers and principals have helped children cope with the initial fear and continuing uncertainty of the earthquakes.

…

What is in question is the way that the Government is going about things. What’s needed now is hard information about how and why decisions are being made about our schools. Some of the figures which have come to light so far have not been encouraging. The ministry told The Press this week that Woolston School’s roll was 220; its principal said it was 265 and growing.

The above is just the quantitative analysis. The qualitative analysis (i.e., the ‘passion’ the editor refers to), if possible, is far worse:

“changes being thrust upon communities in Christchurch”

“I really am finding it hard to put into coherent words my contempt for the cruel announcement”

“shows a complete lack of respect”

“chaotic announcement … The minister is using chaos and confusion to get rid of hundreds of teachers and support staff … shock doctrine tactics used in New Orleans after Katrina”

“how does she [Hekia Parata] have such total power to destroy communities … a deliberate attempt to destroy what’s left of community so that people will be easier to manipulate”

“the National Government has donned its steelcaps and is putting the boot in”

“The announcement of [Greenpark School’s] closure will rip the heart out of a whole community … this is the final blow”

“the plan to close schools lacks any commitment to the recovery of the people of east Christchurch … families of the east are surely being unfairly sentenced to a future void of opportunity, development and success for their children”

“This is dictatorship … Democracy has been slain by a thousand cuts … This has the appearance of being carefully contrived to kick Cantabrians when they are already down. How many times must we let ourselves be kicked in the guts before we stand up and fight for what is right?”

“Does the Government honestly believe that the earthquakes have also shaken Cantabrians out of their senses? … It [the Government] takes away our future and the heart of our communities … This will destroy Christchurch more than the quakes ever did”

“You can’t go around ripping the heart out of a community, mashing it together with someone else’s heart and plonking it in a new super site and then pretend it’s going to be OK and everyone will be happy. … These are our children and our lives the Government is messing with.”

“the plans for reorganising the school system are a brutal drain … some of the changes seem to be experiments. It’s so much easier to try them on an already reeling community. … This is utterly unfair.”

“It is time for the citizens of Christchurch (and particularly those in the east) to finally say to this Government that enough is enough.”

The Weekend Press editorial (22 September) concluded with a prime example of the sentiment:

One of the affecting letters received this week was an open letter to Prime Minister John Key from Burnham School mother Adelle Scott, published opposite. She writes: “Have our children not been through enough without taking away the one consistent thing in their lives?” Scott reports she voted for Key’s Government twice before, because she believed he would do the right thing for the country, but the Government is now not doing the right thing in her view. Sooner or later the Government will need to consider how its actions will affect its support at the ballot box.

As Adelle Scott mentions, Burnham School, in part, services the families of the troops at Burnham. The school and community have just had to go through supporting each other following the deaths of five soldiers in Afghanistan.

Burnham School is now slated to close.

And on it goes.

In Tuesday’s The Press, Chris Trotter pointed out that it could have been so different:

It is possible to conceive of a world in which the first response of those in authority is not to shut things down and freeze people out.

Directly above his column was this powerful piece from Jane Dunbar – a Press journalist but writing in her personal capacity. In her view,

the announcements made about schools last week defy all logic and were, in their own way, like an earthquake – a sudden, severe, frightening, unexpected form of violence.

On Wednesday, the Reverend Mike Coleman commented on the school closures in a piece that was a stinging attack on the Government‘s lack of involvement of the people of Christchurch in its decisions:

Last week’s announcement of school closures, mergers and relocations is the icing on the cake of disconnect and lack of consultation. It defies belief these decisions for Canterbury schools came as the biggest shock to the ones running the schools.

Principals of the most- affected schools in these Government proposals had no idea of the decisions about to be announced. There was zero consultation with principals, teachers and parents and the impact on their communities. Bombs from Wellington were dropped last week and Cantabrians had no idea they were coming.

How can a principal of a school about to be closed not be part of decisions on its future? Communities like Philipstown are going to be decimated by this decision.

…

How can a school like Chisnallwood, where my own sons attended, considered a jewel in the crown of eastern schools, high functioning with superb teachers, facilities and an excellent principal be terminated?

…

Nothing about us without us! This recovery has been done to us.

Wednesday evening (19 September) somewhere between 500-1000 protestors attended a suffrage day rally. The day commemorates the passage of women’s suffrage in New Zealand in 1893, as a result of the efforts of a movement led by Kate Sheppard of Canterbury.

It was broadened to become the opportunity to launch a petition to ‘reclaim democracy’ in Canterbury. The reporting focused on schools but the intent of the rally was three pronged (taken from a circulated email – not online):

“Three big changes have removed meaningful local democracy:

1. A sweeping array of school closures and mergers threatens to take the heart of many communities away. These school communities have supported us and our children through disaster. Some ideas may be welcomed, others not. Many communities need much more time and support and information. School communities should debate and vote for their school futures via school board elections!

2. Real decision making power has been taken from the voters for Christchurch City Council and given to an unelected Government body CERA with no plan in sight for how this power will be returned. We may not have all agreed with the City Council, but it was ours! Local democracy and city votes must be at the heart of our rebuild!

3. We have lost our right to vote for our Regional Council ECan, which makes decisions about our children’s environment, water, air and public transport. If Government-appointed Commissioners are doing a good job, let them stand for election to win our support!

To recover from disaster we must take people with us. Our tamariki want to grow up with a clean environment, local schools and to be listened to with respect in rebuilding their city. It is undemocratic, unwise and unfair to force rushed change, and experiments while removing our voice. Change must be achieved with the people’s vote through our school boards, city council and regional council.

The school closures, that is, come on the back of all the other ways in which the control over Christchurch and Canterbury’s future has been yanked from the hands of Cantabrians.

For the first time the role of CERA is being explicitly challenged – which is very significant given that it is the central mechanism used by the Government to ‘manage’ what happens post-earthquake.

Garry Moore, a previous mayor of Christchurch, has gone so far as calling for Gerry Brownlee to resign and for the establishment of a ‘Board of Christchurch‘ in order to take control away from those in Wellington and encourage a ‘ground-up’ rebuild.

In the same interview – though slightly confused about the interdependent relationship between structures and processes (as if some processes could operate without structures, or irrespective of structures) – Sacha McMeeking, from strategy firm Catalytic, advocated citizen-wide participation in decision making.

And, finally, a second rally occurred in Hagley Park. At least a thousand children, parents, principals, teachers and other Christchurch citizens turned out (organisers estimated closer to 3,000-3,500 present) – and more is promised:

Rally host Reverend Mike Coleman said if the Government did not put aside the proposals and start listening to the community, they would hold a march.

That was the reaction.

Reacting to the reaction

Predictably, damage control and political management (visible and, no doubt, behind the scenes) has kicked in, promptly but not necessarily effectively.

The first strategy was to blame it on the media (for breaking an embargo) – here’s Ministry of Education CEO Lesley Longstone pointing the finger in that direction – and then imply that everyone has over-reacted because they are only ‘proposals’ and now comes the ‘consultation’.

To say there is scepticism over the consultation process would be an understatement – as we’ll see.

Second comes ‘divide and conquer’. One of the quickest principals to respond – and one of the most damningly articulate – was Shirley Boys’ High School Principal John Laurenson.

Last Tuesday, Laurenson and the Board Chair, Toney Deavoll, met Ministry officials and gained a four year guarantee that they would remain on the same site:

After today’s meeting, Deavoll said the ministry appeared to be ”strongly supportive” of retaining Shirley Boys’ High as a single-sex school in east Christchurch.

”We certainly got a very strong indication that this is the ministry’s intent.”

He said the merger proposal was not discussed at the meeting because the school and the ministry did not see it as an option worth pursuing.

Third, you thank your lucky stars that fronting the Secondary School Principals group is Trevor McIntyre, Principal of Christchurch Boys’ High School.

On the day of the announcements, McIntyre, who was extensively quoted in the New Zealand Herald, must have been one of the few principals – perhaps the only one – who gave the announcements an instant ‘thumbs-up‘:

While some parents and staff are still coming to grips with the shock announcements, others have taken a more pragmatic approach.

Christchurch Boys [sic] High School principal Trevor McIntyre said the earthquakes had given the Government an opportunity to upgrade a creaking schools system that was vastly undersubscribed even before the earthquakes.

Many of the schools earmarked for closure are in the eastern suburbs, and small Banks Peninsula settlements, which were hit hardest in the thousands of shakes since September 2010.

There were around 4000 empty desks before the quakes hit but with a further 4500 children leaving the area since the disaster, critical “education dollars” were being wasted on maintaining the empty spaces, he said.

“There wouldn’t have been a principal or a board member a month ago who wouldn’t have agreed there needed to be changes in Christchurch,” Mr McIntyre said.

“A vast amount of money was being wasted on maintaining empty classrooms and I think everybody agrees we were well over capacity anyway.”

While he accepted that the Government’s media management of the announcement “could’ve been better”, he said he was happy for bureaucrats to make the tough decisions on who should close.

If it was left up to the schools, they would also [sic] say, “Not us”, he said.

The ministry has made it clear that these were only proposals, he said, and there would be plenty of consultation to come, especially once final geotechnical reports were completed.

That is, immediately after the announcement he was singing from a Hymn Book whose cover was as blue as a CBHS blazer.

It is hard not to notice a one dimensional analysis of the issues – economic efficiency. Others’ repeated, impassioned comments about schools being the ‘heart of a community’ (present in so many letters to the editor, for example) find no echo in McIntyre’s reported comments in the immediate aftermath of the announcements.

The announcements, in McIntyre’s mind, appear to have been all about earthquakes, shifting demographics, over-capacity and, consequently, “wasted” education dollars.

Days later, secondary school principals, led by Trevor McIntyre, then emerged, apparently happy, from a “behind-closed-doors meeting with Ministry of Education officials“. Unspecified ‘information’ was presented which, according to McIntyre, was,

“just information that we needed and I understand that last Thursday it was difficult to give it to us all.”

What information was this, such that it was “difficult to give .. to us all” on Thursday, but relatively painlessly communicated “to us all” some few days later?

It must have been very comforting information. Shirley Boys’ High School Principal John Laurenson was left with “very few concerns” and thought that “[i]t’s kind of exciting“.

This was the sort of meeting that makes you wish you had ‘fly-on-the-wall’ abilities. Secondary schools, of course, are the ‘winners’ in the announcements.

Apart from the odd – and still unexplained – cases of Shirley Boys’ High School (potentially still dual-shifting with Christchurch Boys’ High School in the official documentation, or even closing) and Avonside Girls’ High School (ditto, but with Christchurch Girls’ High School), ‘affected’ high schools actually see their empires increase in size (super-sizing, we now know, is ’21st century’ education at its best).

Linwood College gets a full rebuild on its ‘lower fields’ (while Woolston and Philipstown Primary Schools move onto its existing site – presumably of no earthquake concern).

The principal of Aranui High School, John Ross, admitted on Morning Report that while his school was “looking at the positives” (about 3min40s into this audio) and could see opportunities, it was a different story for those facing closure.

Indeed, for intermediate and primary schools that are affected, ‘opportunities’ are not at the forefront of their thinking. Leaving their meeting with Ministry officials some principals described it as “clear as mud”:

Primary school principals ‘confused and angry’

In summary, from their perspective the proposals lacked detail, were ‘contradictory’ and often appeared to be based on incorrect data. Also, local Ministry of Education officials seemed out of the loop and needed to clarify their answers by telephone with the Ministry in Wellington before responding to questions, as Coral Ann Child, the Ministry’s earthquake recovery manager conceded in this audio (about 3min00s into it). She argued that it simply showed they were drawing on the “Ministry team” for “specific details” that presumably were not known by local staff.

Given this ‘team’ approach, I wonder how often members of the “Ministry team” up in Wellington, like Education Secretary Lesley Longstone, telephone local ministry officials in Christchurch before answering questions?

An unkind interpretation is that local officials knew little about the rationale or data behind the proposals so felt nervous answering questions about initiatives they had minimal involvement in generating.

Of course, the big problem with consultation ‘after the fact’ is that it raises suspicions that the consultation is largely window-dressing – with some token concessions here and there to provide an impression of ‘flexibility’.

As Will Harvie put it:

Cantabrians are unusually touchy about consultation these days, probably because so little dialogue is underway and the changes afoot so massive and permanent.

The Ministry of Education is in print again today stressing the announced plans are ”proposals” and consultation is underway.

The suspicion, however, is that the decisions have been made, the consultation too late.

Similarly, the Weekend Press editorial (22 September) reminded Hekia Parata that, while she,

rightly points out that dozens of community meetings will provide opportunity for communication and engagement.

That process, though, will be enhanced if the Government drops the patronising tone it has so far adopted towards our communities. We are not schoolchildren ourselves; we do not need lectures and we don’t need bureaucratic flim-flam. We don’t need a minister reminding Christchurch people that they have been under “intolerable stress”. We don’t need her to tell us about living with uncertainty when we are still suspicious of the very ground we walk upon.

More ‘consultation’, perhaps, but less democracy.

The view from afar

For those not living in ‘Greater Christchurch’, it’s important to realise the nature of the reaction.

Elsewhere in New Zealand, this seems to be a relatively minor political story competing with what must seem like more pressing, and perhaps more significant, issues (e.g., the conflict over water rights, the Banks-Dotcom saga, the bleeding sore that is child poverty, etc.).

By contrast, the story about the schools proposals has been framed, mainly, as a Government ‘political blunder’ arising from a communication botch-up.

Yet it is far more than that. Understood properly, it links inextricably to each of the stories just mentioned that are grabbing the national attention. As I said at the start, what is happening here in Christchurch is like a long lesson in the raw imperatives driving so many issues at present in New Zealand.

Comments in the few letters in The Press supportive of the Government’s announcements (about three to date) are almost uniformly from outside Christchurch and seem motivated by the ‘politics as usual’ mode of interpretation.

A correspondent to The Press (22 September) from Mosgiel, under the apt title ‘Labour did it too‘, expressed amazement at opposition to the school closures and mergers. After detailing the closures of five Taieri schools by Trevor Mallard, the correspondent concluded by wondering whether,

the demonstrations [in Christchurch] would have been so intense if a Labour Government had made this decision.

At a personal level I can respond unhesitatingly with “Yes, they would”.

At a more general level, these sorts of comments show that many from outside Canterbury don’t understand what is happening here – and its relevance for all of New Zealand.

What is happening here is not “way bigger than politics” – as David Shearer claimed when he visited Christchurch earlier this year (see my post on that here) – instead it is ‘way big politics‘.

What has been stewing here in Christchurch for over a year and a half is something that is certainly ‘bigger than party politics’ but that doesn’t make it non-political, or transcendent of politics. It reveals the dynamic underpinning the present political scene throughout the country.

The battle – and that’s clearly now what it is – is one of the oldest political battles in human history.

It’s the battle of a people to have control of their destiny.

It’s the struggle of a people embedded – for better or worse – in their place, their lives and their broken world trying to get through the stress, the pain, the loss and the dissolution of their neighbourhoods against a backdrop of external power imposing itself upon them repeatedly.

It’s also a contest over the priorities of a society. Put starkly, it’s between organising primarily for ‘production’ or primarily for ‘reproduction’.

Production is all about ‘efficiency’ and prioritising outputs per unit input. Because of that, it inevitably frames education as the pursuit of work-readiness. It’s concern is maximising economic benefits while reducing education’s economic costs.

More generally, prioritising production means reshaping and rebuilding an entire city and province – if you get the chance – to make it a sleek generator of growth. Cities become entry points for capital and exit points for resources and profits. People become ‘human capital’. As much as possible (i.e., as much as you can get away with) is arranged to that end.

By contrast, reproduction is not, of course, just about having children. It’s about regeneration in general. It’s about regenerating individuals, families and communities (the “bleeding” communities of which John Laurenson spoke).

Prioritising reproduction, in this sense, means seeing education as a process of developing people in ways that allow them, first, to regenerate and sustain themselves throughout life and, by doing so, regenerating the communities and societies they belong to. It is less concerned with narrow, measurable ‘output’ (like this pointless exercise) and more concerned with the quality of the people, places and communities that get reproduced. It is the use of resources principally to that end.

The Government’s response in Christchurch has primarily been about the supposed urgency of creating a ‘business-led’ recovery (or is that simply business-friendly? – if you are one of the chosen businesses, of course). That brute urgency in the service of the supposed economic priorities has left people struggling in its wake, gulping down sickeningly salty water as they try to keep their heads above the surface.

It may be dressed up in words of caring for communities – in the vocabulary of ‘reproduction’ – but that carefully chosen partner-word, ‘enhancement’, has become the driver and determinant of this Government’s ‘recovery plan’. That word is now, plainly, just a euphemism for re-creating Christchurch from the bottom up to serve the demands of production.

It’s happened to our regional council, it’s happened to the central city. It’s why so many have been left in desparate living conditions and why so many more live in a stressful limbo-land caught in the sticky miasma of EQC, Insurance Companies, CERA and the neutered City Council.

And now it’s happening to our children.

Well, that’s how it feels. And feelings have a rationality that threads right back to our evolutionary struggle to sustain ourselves.

As some have put it, feelings arise when nature has already done the thinking, the calculations, for us. After all, nature has seen these battles countless times before.

Now, in Christchurch, it has quite rightly taken charge. And it has done so because this is not just messing with our city – it’s messing with our children mixed up as they are in such deep hopes and such powerful, aching meanings for what the future holds.

If ever there’s a living symbol of the imperatives of ‘reproduction’ over production – of deep recovery first and ‘enhancement’ second – it is our children.

That’s why feelings are ‘running high’ in this city.

We’re canaries at the coal-face in the coal mine that New Zealand is fast becoming.

[To be continued …]

Another great post. Thanks.

And yeah- like many, I’m increasingly angry.

Thanks Rob.

We feel what we feel. The important thing is how we respond to – and use – those feelings.

Harnessed properly, even anger can be a powerful laser-beam for the good.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Another great post – thank you for taking the time to read and analyze the horrible stuff being foisted on us by central government so that we don’t have to.

The rest of New Zealand should sit up and take notice of what is going on here. Do they think this or any future government will operate two different forms of education structure? Of course not, if we get the amalgamation of schools trialed in Christchurch then the concept will be rolled out to the rest of the country – by force in most cases.

Whether the policy is any good or not I can’t say but it is very clear that there is a “teaching moment” here about what governments mean when they say they are “consulting the public” on a policy proposal. My heart sinks every time I hear of yet another group who are disappointed with the outcomes from being consulted by governments, central and local. There always seems to be a major mismatch between the general public’s expectations and what governments actually do by way of consultation and the results of consultation.

Before I launch into why I think that is so let’s be clear we are talking about representative democracy. The minimal version of this form of democracy is voting in your representatives to govern as they see fit and voting them out later if you don’t like what they do. In this context any form of consultation is a “luxury” not a right. Having said that the requirement to consult on significant proposals is built into the Local Government Act 2002 and there may be some aspect of Administrative Law that requires central government to act reasonably as well.

As I see it there are three flavours of policy consultation:

• Pro-active “blue skies”

• Passive “blue skies”

• “Just checking” on a specific proposal

In the first the public agency actively seeks out affected parties to engage with to develop a policy proposal from scratch. While expensive and time-consuming this approach will almost always generate a lasting solution that is relatively easy to implement. Politically it is very unattractive as it does not generate enough political payback and requires giving up power and control.

In the second the agency advertises the opportunity to submit on a proposal – the proposal is not detailed and may be as “blue skies” as “tell us how you want your town to be in the future”. The key here is that the submitters are self-selecting. How well do these work? Consider the 550-odd responses received to the first “Directions” document. 500 responses from a population of about 500,000 – that’s a 0.001% response rate. Play with those numbers and you could get it up to 0.002%. That’s one school class inside a packed AMI Stadium crowd. By itself that response rate is not necessarily bad – sometimes larger organizations submit on behalf of all their members. But it is criminal how those responses are sometimes analysed and used.

The third style is by far the most common – sometimes it is used with #2, but mostly it happens in isolation. Thanks to a wonkette who explained this all to me I now understand that when there is a firm and detailed proposal on the table the agency generally is not interested in what you think of the proposal. The point of going to public consultation is to find out if the proposal will have any impacts that have not already been taken into account (“Oh, didn’t know that, thank you.”). The agency has no obligation to take note of like/don’t like submissions especially the fill out a template and add your name type. Obviously there is a tipping point when politicians will take note of quantity not quality but who can predict where that is?

I reserve particular odium for the second type of consultation. To justify the firm proposals that turn up in final consultation politicians and policy analysts alike sometimes treat the information as though it were a randomly selected sample survey which it clearly is not. Look at the quotes above: “You said…” It wasn’t me it was one of the 0.001% but the wording implies a scientifically sound finding that at least 50.1% of the whole population agree with the statement. Unless there was a RSS survey to confirm the findings the policy analyst responsible for drafting those lines should resign immediately because of the unethical use they made of the data they gathered.

It is cynical to go through the motions of public consultation all the while knowing how easy it is to bend the process to justify a pre-determined position.

Sorry about the awful maths. 1 in 1000 is, of course, 0.1% (still not an inspiring percentage). Is there an edit capability in this blog?

Hi Kumbel,

That’s an interesting dissection of the consultation possibilities and realities in politics today.

Most ‘consultations’ that derive from policy preferences (or ideology) are obviously not exercises that the initiators are going to see as opportunities for throwing out their own policy preferences/ideologies.

I think a more honest form of consultation in those cases would be to say, ‘Look, you can suggest these sorts of things; A; B; C (e.g., timing, process, etc.) but the following are non-negotiable and not open for consultation: X; Y; Z’. That would at least show the true extent of consultation involved and envisaged.

On the ‘edit’ question, I’m not very technology savvy. From my end there’s an editing capability but maybe not from a commenter’s view. Sorry about that. I’m open to suggestions as to how to change that.

Thanks for your comment Kumbel. Well worth reading.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Pingback: The school of hard knocks and ‘the curious incident of the dog …’ – Part II | The Political Scientist

Pingback: From the ‘Gomer Pyle’ files – Boys’ High Head Trevor McIntyre Resigns | The Political Scientist