Poverty of Morals

We are moral animals.

But, so far as I can judge, in politics today our moral instincts are operating in a way that generates the worst moral outcomes.

Metiria Turei’s recent confession (a moral notion) at the launch of the Green Party’s welfare policy – and the reactions to it, culminating in her excluding herself from a Ministerial position in any Labour-Green post-election cabinet – provides a revealing example of the operation of our ‘moral sense’ in politics and in society.

Putting aside the political fate of Metiria Turei, what it shows is that there is a moral poverty in New Zealand – especially when it comes to poverty.

And that particular type of moral poverty has leached into the heart of political calculations – even, it seems, on the left of New Zealand politics.

Before I start I want to make something clear.

How we judge Metiria Turei’s actions at the centre of this confession is a microcosm of how we judge our current welfare system – the one we’ve had ever since the 1990s.

It’s a judgment, in fact, that goes far beyond the area of welfare. It is about the entire trajectory (economic, social, cultural) those decades-old reforms have propelled us along.

It’s about the whole package because the structure of our welfare system and all its rules and compliance requirements are utterly central, inherent features of the 1980s—1990s reforms and the rhetoric and ideology upon which they rest. They go together with the financial deregulation, the ‘labour market reforms’, ‘fiscal responsibility’ and privatisation like a horse goes with a carriage or a bat goes with a ball — or a ball goes with a chain.

So, this matters – far more than many realise.

And, finally, it matters just because we’re moral animals.

Like almost every aspect of us as a species, our ‘moral instincts’ evolved within a very different set of social arrangements than the ones we find ourselves in today. (Here, I’m accepting the argument of New Zealand’s own Richard Joyce in his book ‘Evolution of Morality‘ that morality has evolved, but will be drawing my own conclusions from that.)

Just as our predilection for sugar and fat in an ancient environment rare in those food elements has been exploited by the modern food industry to the point of creating disease epidemics so, too, our particular set of moral biases and ‘intuitions’ has been exploited by political and economic systems to our collective detriment.

The most important difference between the environment within which our moral tendencies evolved and the world we now live in is in the scale of the social world. In comparison with the modern world, work on extant hunter-gatherers suggests that hunter-gatherer groups are, and were, extremely small, nomadic, low-density, non-hierarchical and wealth-egalitarian with minimal division of labour.

Not quite like society today, then.

Direct interpersonal interactions (‘social exchange’) comprised most of the social world. Vast bureaucratic institutions and governmental mechanisms were unknown and unnecessary. Social harmony and functioning were a product of interactions that, as a by-product, led to humans’ highly characteristic emotional lives – involving experiences of pride, shame, guilt, gratitude, envy and the like.

Our moral ‘senses’ were adaptations to that world – but not to this one.

For example, take our emotionally deep and visceral focus on cheating and lying.

As a study by Cosmides, Barrett and Tooby in 2010 confirmed, given the prevailing social and material conditions for our evolution one highly attuned moral sense was detection of those who ‘cheat’ on social exchanges based on reciprocity or some other obligation.

In an environment in which the future reciprocity of other, particular individuals underpinned social solidarity the identification of those individuals who cheated was paramount (as was feeling disgusted at, and affronted by, their behaviour).

Along with a need to detect cheating came the moral sanction against lying.

Lying is tactical deception to avoid being detected as a cheater. It’s the next step in the human-level (or primate) escalation of the arms race between cheating and cheater detection. (The irony is that, according to this paper, in evolutionary terms and as a species, we may well lie just because we are cooperators — the two are linked.)

Put bluntly, in evolutionary terms we kept each other in check and so generated social stability, cooperation, and success by constant interpersonal moral policing. In fact, in such a flat, egalitarian society it was about the only tool available for that job.

That’s why, still today, it can feel just so ‘natural’ and righteous to despise and shame the suspected liar and the cheat.

But that moral armoury no longer works. It now has what economists might call ‘unintended consequences’. Just as a preference for sugar and fat worked well in our evolutionary environment but causes problems today, so too our moral senses that were designed for a very different social world no longer work to good effect today.

Channelled by prevailing rhetoric and narratives our moral impulses generate immoral outcomes. With our rapid swing towards individualised competitiveness over the past few decades that old morality — designed to ensure cooperation — increasingly creates division, instability and yet more competitiveness. It has also locked in a high degree of suffering for a remarkably large proportion of the population.

We may never come across the people we come to viscerally despise for what we perceive as their lying and cheating ways – yet we still despise them. We may never have better than third, fourth or fifth hand knowledge about them; knowledge which is itself selective and, via media, often attributed generically to entire groups of people.(In-group — out-group biases then follow as a matter of course, which is often not a pretty sight.)

And most importantly, we may never truly understand the lives and conditions that gave rise to the actions we so easily condemn.

When all humans lived much the same lives, encountered much the same challenges and had intimate knowledge of the personal history of those they would hold to account, moral judgments at least stood on some clear and relevant foundation.

The same process of judgment is today delivered via impersonal regulations, laws and institutions (often themselves staffed by people under huge structural stress) with overweening power over the lives of individuals and families. And those individuals and families face radically different degrees and types of challenges and experience vastly different lives from those who judge them.

In that world — the one we live in today — there is only a faint possibility that, in any particular case, the judgment will be morally appropriate.

That we still operate on those species-old moral intuitions when it comes to policy is, at best, unwise. At worst, it’s immoral.

It also ignores the thousands of years since our hunter-gatherer past when culture after culture, civilisation after civilisation has grappled with new ways, new moral bases that are more appropriate for large-scale complex societies.

Today, perhaps, we need a moral sense that is less focused on judging others (about whom we increasingly understand so little) and, instead, is more aware of the pitfalls of judgment. A ‘moral intuition’ that goes beyond legalistic measures of ‘moral behaviour’ and has a bit more faith in the long-term benefit of showing generosity of spirit to others.

Bleeding-heart ‘idealism’? Well, actually quite ‘pragmatic’. You might even call it ‘pragmatic idealism’, to borrow a phrase.

So pragmatic that some countries have implemented it. Here’s the opening sentences from an official Finnish website as it introduces that country’s social security system:

Finland enjoys one of the world’s most advanced and comprehensive welfare systems in the world, designed to guarantee dignity and decent living conditions for all Finns. The Finnish social security system reflects the traditional Nordic belief that the state can intervene benevolently on the citizens’ behalf.

Now, let’s return to Metiria Turei’s confession and the events that have followed from it.

Turei’s confession was that, in the early to mid 1990s when she was in her early 20s, she misrepresented her living circumstances – that is, lied – in order not to lose the accommodation allowance. It’s worth extensively quoting the relevant part of her speech:

Today, I want to talk about an issue that I believe is the true test of us as a Party, and of who we are as a country.

Our response to this challenge will define us in government.

It is also an issue that is very personal to me, it is why I have persisted, to be in a position to fix it – so that we, as a Party, can fix it.

I have talked to you before about my time on the DPB. I was a single mum, raising my beautiful girl Piupiu while doing my law degree, and I was on the benefit.

I had a great case worker at what we now call WINZ, who treated me with respect.

I had the training incentive allowance as a grant to help me pay my fees and childcare. I had great support from my family and my baby’s dad, and his family too.

Like most people who receive a benefit, I was so careful about managing my money.

I’d go to the bank every fortnight on dole day. I’d withdraw all my money, in cash, then split it up into small amounts, wrapped up in rubber bands with little notes about what it was for.

I knew exactly how much I had for our bills, our rent, our food. But whatever way I split it, I still didn’t have enough to get by at the end of the week.

What I have never told you before is the lie I had to tell to keep my financial life under control.

I was one of those women, who you hear people complain about on talkback radio.

Because despite all the help I was getting, I could not afford to live, study and keep my baby well without keeping a secret from WINZ.

Like many families who rely on a benefit, Piu and I moved around a lot when she was little.

We lived in five different flats with various people.

In three of those flats, I had extra flatmates, who paid rent, but I didn’t tell WINZ. I didn’t dare.

I knew that if I told the truth about how many people were living in the house my benefit would be cut.

And I knew that my baby and I could not get by on what was left.

This is what being on the benefit did to me – it made me poor and it made me lie.

It was a stressful, terrifying experience.

At any moment, WINZ could have caught me and cut off my benefit.

They could have charged me with fraud and made me a criminal as well.

I got through it, of course, as you can see.

Not everyone does.

We know at least one woman committed suicide after being accused of fraud and chased by WINZ for a debt.

That fraud never happened, the debt was not owed. But by then it was far too late.

In another public case, a woman known only as Kathryn, was trying to recover from the death of a child at the hands of her violent partner, and was hounded, persecuted and eventually jailed by WINZ.

She did everything she could to improve her life and yet at every turn she was punished by the welfare system set up to help her get by.

There is something deeply, deeply wrong with our welfare system and how we treat the families who depend on it.

It drives people to violence against others and themselves. It keeps children in filthy campground cabins until they sicken, it tortures and harasses women grieving for their lost babies.

It makes ordinary, good people, like myself, like Kathryn, suffer because they do their best to survive.

I know that by sharing my own story here today, I am opening myself up to criticism. It may hurt me personally and may hurt us as a party.

But I also know that if I don’t talk about what life is really like for beneficiaries, if the Green Party doesn’t, then who will?

I think the answer to her final question is pretty clear, at least going by the media commentary: Currently, hardly anyone. Certainly very few in the present New Zealand Parliament.

In essence, Turei was making the argument that the conditions surrounding welfare in this country, at least since the 1990s, are so punitive that many people genuinely find it necessary to choose between lying and seriously harming their own wellbeing or that of their children (or both).

You either believe that or you don’t. The bulk of evidence suggests that it’s true. So, if you don’t believe it you’re either unfamiliar with the evidence or no amount of evidence could convince you. If the latter is the case then there’s a moral problem alright, but it’s not a problem with the fraudulent ways of beneficiaries.

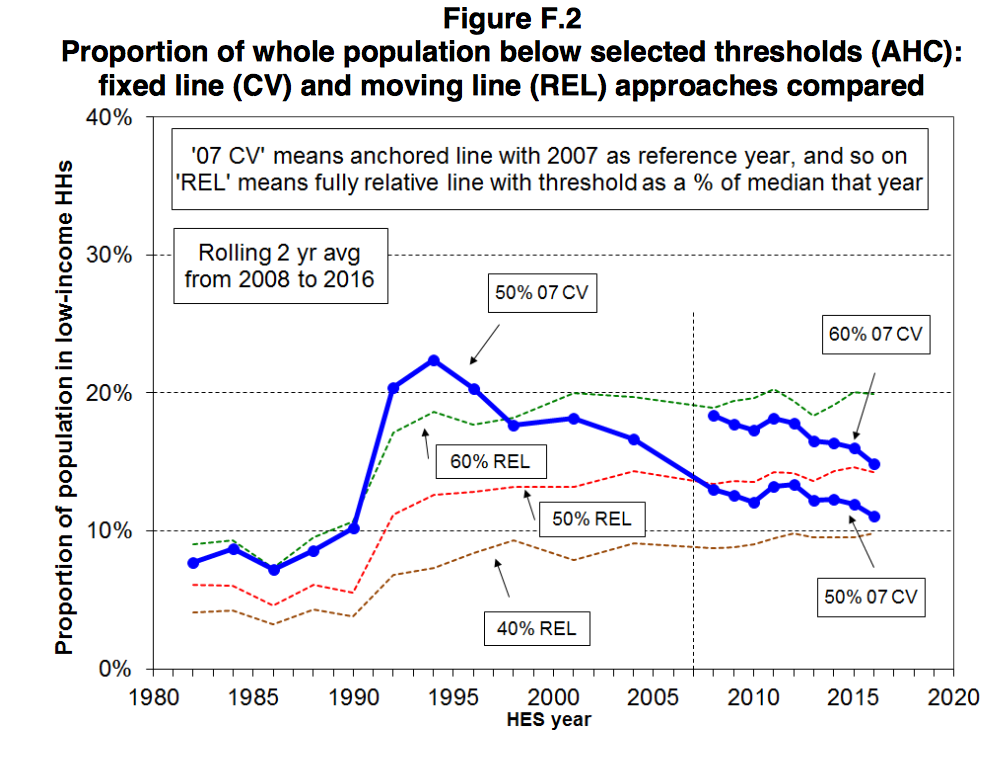

First, by any measure, in the first few years of the 1990s economic hardship in New Zealand more than doubled. Here’s Figure F.2 from the Ministry of Social Development’s July 2017 report ‘Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2016‘:

MSD July, 2017: ‘Household incomes in New Zealand: Trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2016’

From: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/monitoring/household-income-report/2017/2017-incomes-report-wed-19-july-2017.pdf

All measures relative to contemporary incomes (40% REL, 50% REL and 60% REL) show the same trend of steady but small increases in the proportion of low income households in New Zealand, After Housing Costs (AHC), since the mid-1990s.

So, there was, and is, hardship. (Incidentally, when Turei was on the domestic purposes benefit that was shortly after what, by any measure, was more than a doubling in rates of economic hardship. Quite a context within which to be fearful of your economic prospects while on a benefit.)

Second, there have been sharp increases in the number of complaints received about Work and Income New Zealand (WINZ). By 2015, for example,

A staggering increase in complaints by Work and Income clients has been written off by a Government ministry who blames the increase on more Kiwis using its services.

Since National took office in 2008 the number of complaints about incorrect information being provided by Work and Income has increased by 122 per cent from 537 complaints in 2008 to 1197 this year.

But the Ministry of Social Development has defended its record saying, while the rate of complaints have increased since 2008 – “so too have the number of people seeking assistance from the ministry“.

“In 2008 there were 850,532 people receiving a benefit from the ministry. This number grew in 2009 to 923,105 with the increase in part attributed to the impact of the Global Financial Crisis and the growth in our ageing population,” a ministry spokeswoman said.

To date there are 1,045,837 clients on Work and Income’s books and “overall the number of complaints we receive are small in comparison to the large number of transactions completed by our staff on a daily basis”.

As well as complaints about ‘incorrect information’, however, there were also substantial rises in complaints about ‘staff attitudes’, ‘procedures’, ‘action taken’ and ‘timelines’:

On top of the increase in incorrect information complaints, there has also been a 62 per cent increase in complaints about Work and Income staff attitudes, and a 66 per cent increase in procedural complaints.

In total, complaints at the Government department have risen by almost 30 per cent from 5695 in 2008 to 7228 this year.

For the record, the increase in number of ‘clients’ – from 850,532 people to 1,045,837 – represents a 23% increase.

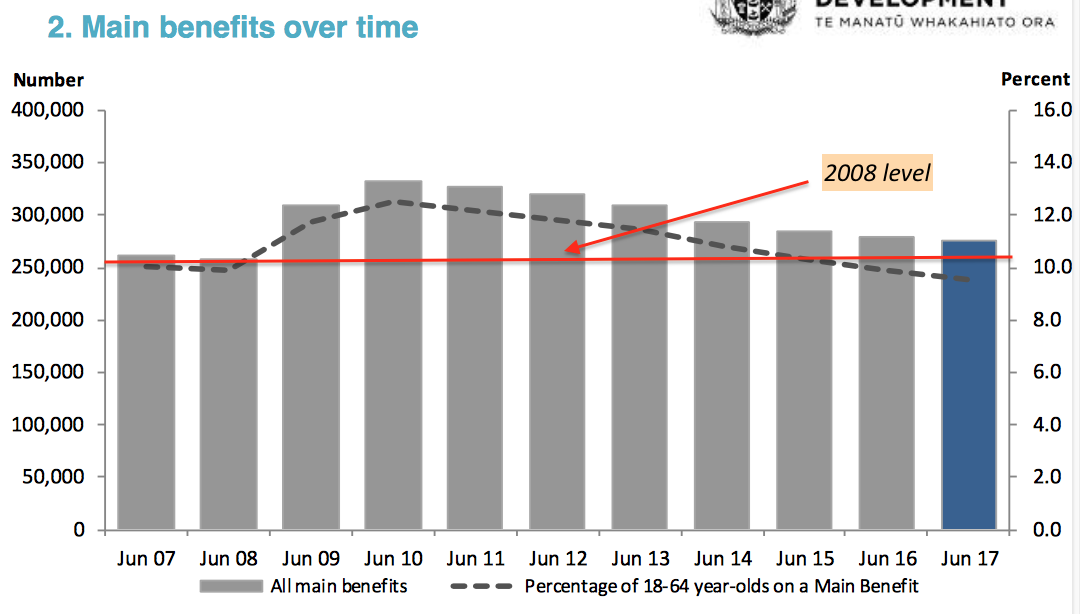

However, during that time the number of ‘Main Benefit’ (i.e., non-superannuitant) claimants had increased only marginally, as this figure from the ‘Quarterly Working-Age Benefit Numbers – June 2017‘ Fact Sheet shows:

MSD – ‘Quarterly Working-Age Benefit Numbers – June 2017’

From: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/benefit/2017/quarterly-working-age-benefits-june-2017.pdf

It may, of course, be that the new superannuitants over that period – who must have represented the bulk of that 23% increase in numbers – were a particularly obstreperous cohort. But, given that superannuitants are not subject to the same compliance requirements and restrictions as other beneficiaries (because superannuation is a universal benefit), it is more likely that those on ‘Main Benefits’ were complaining in far greater numbers and percentages.

Third, there have been increases in individual reports of stress and even death as a result of punitive encounters with WINZ. Most famously, Wendy Shoebridge’s suicide in 2011 was claimed to be partly caused by fraud accusations – later admitted to be false – made against her by the Ministry of Social Development.

Most worryingly, evidence was given to the inquest that ‘performance targets’ for prosecutions of fraud were set by for MSD staff – though Minister Anne Tolley said “I am advised that there is not a quota for prosecutions the investigators must reach“:

She died without knowing who made the allegation against her, or that MSD later downgraded the amount it alleged she stole, from about $22,000 to $5500.

It eventually found she had not committed any offence at all.

More than five years on, coroner Anna Tutton and the lawyers and witnesses at a Wellington inquest heard of Shoebridge’s turmoil, and of a chaotic MSD office, in which staff were alleged to have performance targets based on prosecuting beneficiaries.

The manager and investigator on her case barely spoke to each other, and the manager allegedly swore across the room at staff she disliked, the inquest heard.

The investigator said he never wanted to prosecute Shoebridge. The manager said she was never told of the real risks to Shoebridge.

Fourth, along with greatly increased efforts to prosecute for benefit fraud, the increased reporting requirements, compliance measures, oversight and general administrative surveillance that has characterised the past decade or more of welfare regulatory reform – e.g., as detailed in the recommendations of the Welfare Working Group Report of 2011 (p. 55):

Reciprocal obligations

The notion of reciprocal obligations is at the centre of our proposed model. The welfare system provides support for individuals in need. In return, it is important that individuals take personal responsibility for getting on with their lives. Where it is reasonable, individuals should be expected to actively look for work, and take steps to address their personal barriers to employment. There should also be clear and well managed consequences for those who do not meet these expectations.

And (p. 56):

Clear targets

The number of people on welfare needs to be significantly reduced over the next decade. Absolute targets are important to direct attention to the scale of the problem and to ensure a greater focus across Government and the community on outcomes. Absolute targets also provide a yardstick to transparently measure progress.

This general trend in government social policy, ever since the 1990s, has been towards greater surveillance and reporting at the level of the individual beneficiary and is entirely consistent with the individualistic ideology underpinning the entire history of economic, social policy and public sector reforms since the Douglas-era ‘revolution’ in the 1980s.

It is one of the ironies that a set of reforms trumpeted as ‘freeing the individual’ and which aimed at ‘unleashing New Zealand’s potential’ (or words to that general effect) required as a necessary component of its fulfilment the imposition of greater and greater – and more individually-targeted – coercive measures on particular individuals (and not just beneficiaries).

It goes back to Richard Prebble’s rhetoric when he was ACT Party leader in the 1990s that the most deep-seated poverty in New Zealand is ‘behavioural poverty’.

And that rhetoric, in turn, goes back to U.S. policy debates in the 1960s over the so-called breakdown of the ‘African-American family’. This report from the MSD entitled ‘Ethnicity-based research and politics: snapshots from the United States and New Zealand‘ tells an eerily familiar rhetorical story (the story is too detailed to follow in full here but is definitely worth the read):

As is well known, leaders of the ACT party used the Chapple paper to fuel a backlash against the Government’s “closing the gaps” policy in late 1999 and early 2000. The attacks by MPs Muriel Newman and Richard Prebble were reinforced by favourable commentary on Chapple’s analysis from less extreme quarters, such as Simon Upton’s web-based opinion column (Newman 2000, Prebble 2000, Upton 2000)

….

This article draws on a somewhat similar episode in the history of American policy analysis.

…

As the within-group class differences for blacks began to overshadow between-group racial differences [with the formation of a black middle class], sociologist William Julius Wilson (1978) reported “the declining significance of race” as an explanation of American social outcomes. His pronouncement was promptly taken out of context and used to support the false assertion that blacks as a group had reached parity with whites and that full equality of opportunity had been realised at last (Wilson 1987). For those who held this view, a natural corollary followed: that inner-city blacks who did not take advantage of equal opportunity and did not make the step up to the middle class suffered from strictly personal and behavioural failings rather than systemic or structural obstacles (Gilder 1981, Murray 1984, Sowell 1984).

The virtual moratorium on serious study of black social structure that followed the Moynihan controversy left a void into which conservative scholars poured their theories of behavioural poverty (Wilson 1987).

The concept of ‘behavioural poverty’ is nothing other than a repackaged version of the notion of ‘moral poverty’ that crept into the U.S. political vocabulary in the 1990s, along with the idea of the coming of the ‘super-predator’ juvenile (usually black) with no moral compass because of a lack of guidance from parents and community.

This overblown Chicago Tribune account from the time – with the title ‘Moral Poverty: The coming age of the Super-Predators should scare us into wanting to get to the root causes of crime a lot faster‘ –indicates the degree of moral panic and hyperbolic use of notions of ‘super predators’ and ‘demographic crime bomb’ linked to this ‘theory’ of moral poverty.

Variations on the word ‘scared’ and ‘fear’ dominate its pages. Yet here we are in New Zealand in 2017 basing our entire welfare assumptions on similarly ludicrous ideas about individual failings as the ‘root cause’ of people receiving benefits.

When individual behaviour is seen to be the salient cause of a social issue then the next step is to see the causes of individual behaviour within the individuals themselves. Once these cognitively easy but morally and intellectually lazy steps are taken we’re only a hop, skip and a jump from self-righteous anger at the lying and cheating these ‘flawed’ characters indulge in.

And so here we are.

A society that has allowed these ‘moral instincts’ to run pretty much amok. A society where hundreds of thousands of people are treated, at best, with sideways suspicion. A society where the institutions of state are set off the leash to hound and corral these same people, like out of control huntaway dogs rounding up sheep into a pen with liberal and persistent use of nips and bites.

As James Shaw, co-leader of the Green Party, said on TVOne’s ‘Q and A’ programme: “We have in New Zealand an undercurrent of vitriol towards beneficiaries and towards poor people.”

Perhaps the only inaccuracy in that statement is the word ‘undercurrent’.

Frankly, there’s nothing remotely hidden about these harsh sentiments, both in the public realm and in innumerable interpersonal conversations and exchanges around the country. It is out in the wide and wild open savannahs of moral righteousness. And that ‘born free’ element to the vitriol is largely because those who express it have this strong inner sense and feeling — backed by hundreds of millennia of evolution and recently allowed to run rogue by septic political and economic ideologies — that they are doing what is morally best.

But it isn’t for the best.

Leaders with true moral depth see this truth instantly. So, rather than pander to such a feral moral sense they look to lead it back to its original function — to build a stable, cohesive society rather than an ugly, unstable and divided one.

Sadly, that project of a morally better society received a blow as the week drew to its, in retrospect, inevitable denouement.

The day Metiria Turei announced she would not seek a Ministerial seat in any Labour-Green government that might form, post-election, another political leader took it upon herself to signal, wittingly or not, that she accepted — or perhaps simply electorally wary of — that vitriol, that denigration of beneficiaries and the poor.

Jacinda Ardern achieved that through what others saw as her ‘tough’ or ‘strong’ leadership in making it clear that, if Turei had not made her decision, the Green Party co-leader would not have been welcome in any cabinet over which she reigned as Prime Minister.

It was revealing that Ardern would not say, under repeated questioning, just why she “came to the same conclusion” as Turei over her (Turei) not being available for a Ministerial post. Turei’s reasoning was that removing herself from contention would take away problems for her party and the MOU with the Labour Party. In fact, as Toby Manhire at The Spinoff put it:

It was almost immediately confirmed that Turei’s decision was ultimately determined by their senior Memorandum-of-Understanding sibling. Of Labour’s position, Turei acknowledged she needed to “respect their concerns”. And, poignantly: “I am offering this to them.”

So why did Ardern want the offering to be made? If it was that ‘electoral fraud’ — even of such a minor character — was a step too far then why not say it? At least then it would be clear that Labour were not backing off because of the actions of a 23 year old solo mother on a benefit under the grim regime of the early 1990s.

And if it was because of the electoral fraud why did Ardern not have the instincts to use it to make a point about how she would never exclude someone based solely on their genuine efforts to look after their child and the decisions they made to do that?

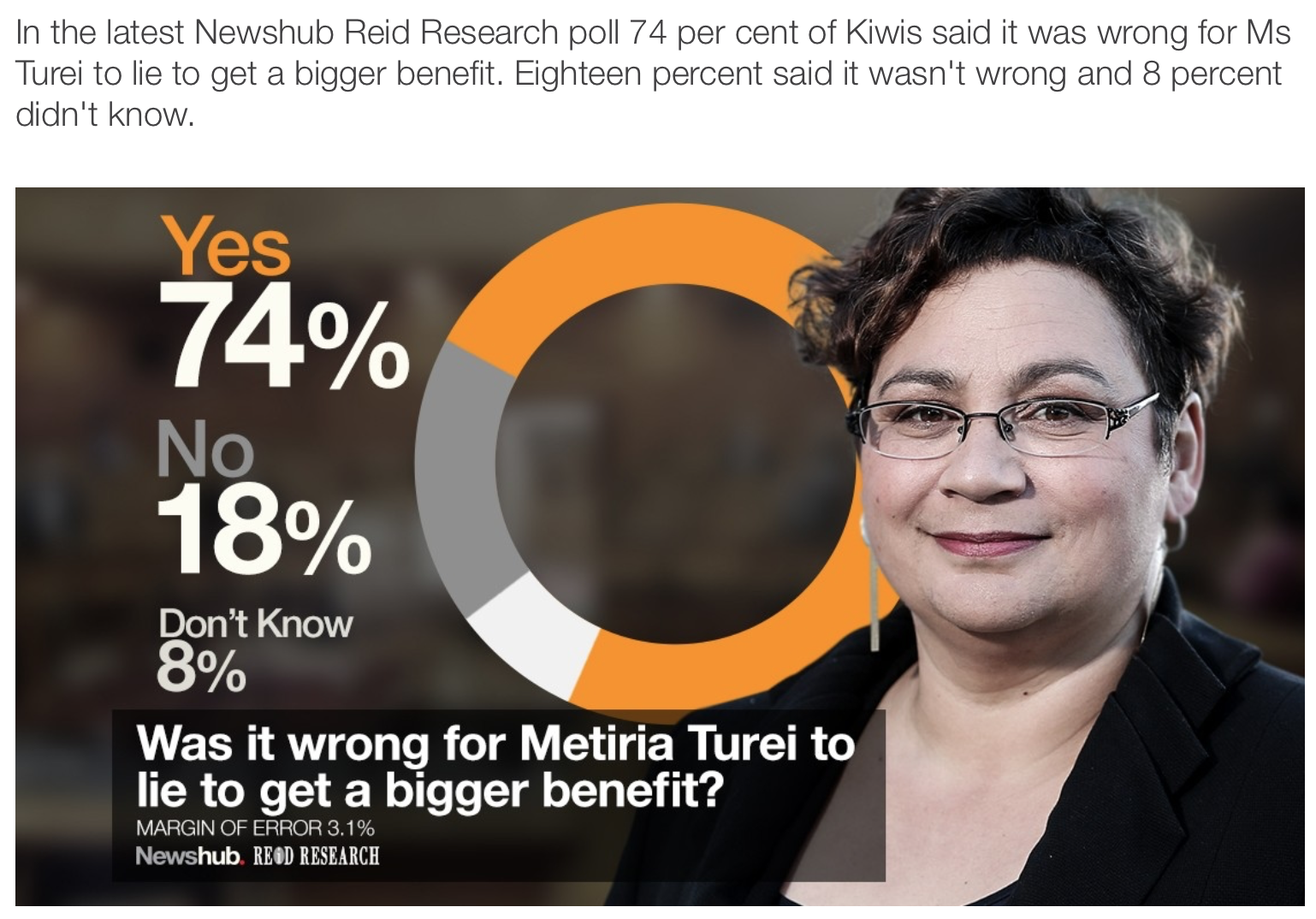

Clever electoral politics? Perhaps – after all, a poorly framed ‘poll’ by Newshub found that 74% of New Zealanders thought she was ‘wrong’ to have lied about her circumstances over 20 years ago:

From: http://www.newshub.co.nz/home/election/2017/08/newshub-poll-most-kiwis-say-metiria-turei-was-wrong-to-lie-to-winz.html

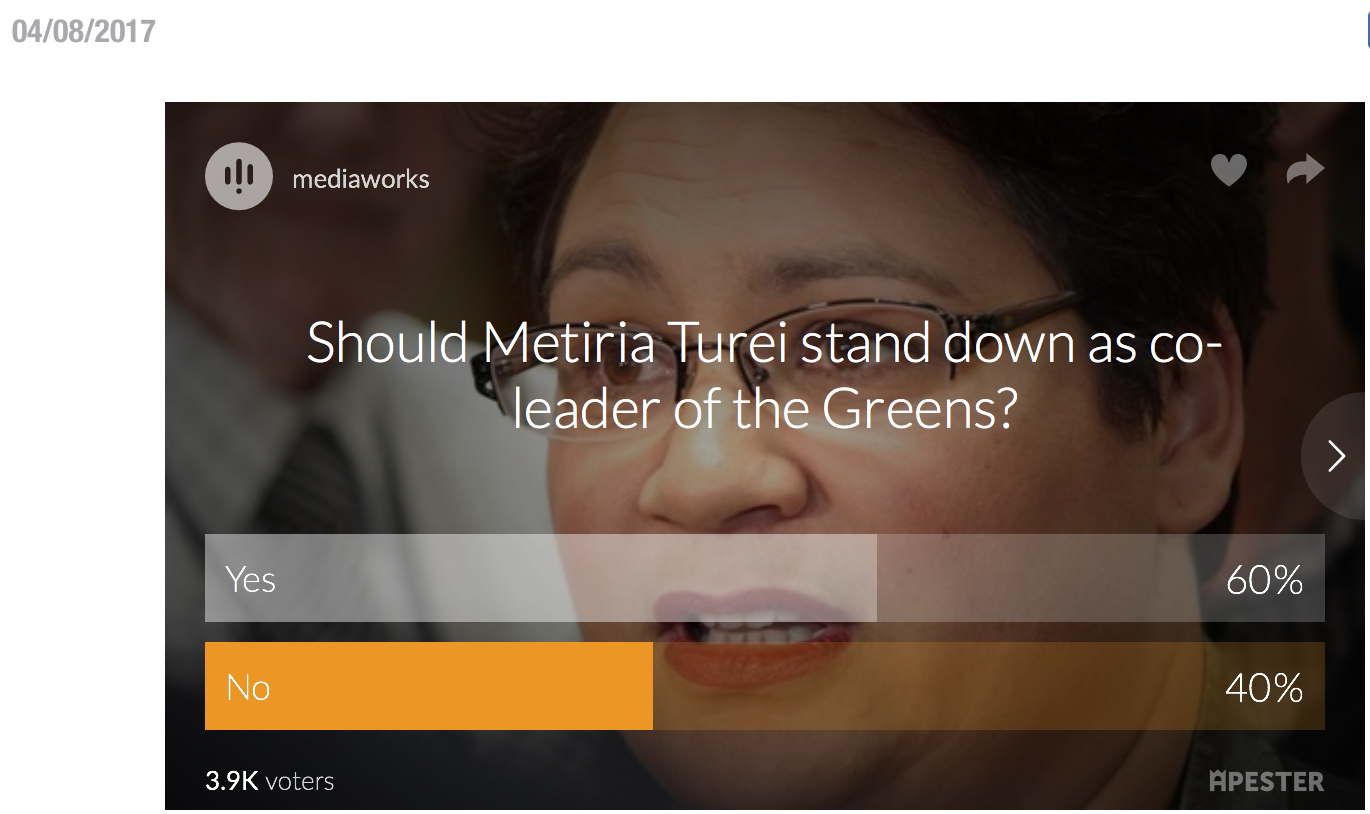

And, just to reinforce that there’s nothing like unscientific polling to make copy to fill news websites, Newshub followed immediately with a ‘poll’ asking if Turei should resign as co-leader after the discovery that she had provided a false address in 1993 in order to vote for a McGillicuddy Serious Party candidate — and friend:

Another Newshub ‘Poll’

From: http://www.newshub.co.nz/home/shows/2017/08/poll-should-metiria-turei-stand-down-as-co-leader-of-the-greens.html

Clever politics it may well be.

But, as it stands, Ardern’s silence on the reasons she believed this was the ‘right decision’combined with her firmly stating that she would have stopped Turei from being in Cabinet if she had not ruled herself out has led to one extraordinarily sad consequence — those who participate in the ‘vitriol’ against beneficiaries and poor people have just had that vitriol silently ascented to by the leader of the Parliamentary left.

So Ardern has firmly planted her ‘pragmatism’ foot on the ground but, on this issue of the punitive treatment of beneficiaries, will we see the ‘idealist’ foot fall? Ever?

Ardern had every opportunity to lead, not just politically but morally. For whatever reason, she missed that opportunity. And it was an unprecedented opportunity we may not see again for many years.

We missed the chance to confront, as a nation, what we have been doing to ‘our own people’ – to ourselves – for three decades.

But, more importantly, because of how central the treatment of beneficiaries and the poor is to the neoliberal structuring of the state and the economy, we have also missed the chance to confront and weigh in the balance — out loud and with clear and honest eyes — the state of not just New Zealand’s welfare regime but the morality of our direction as a country.

And we are all the poorer for that.

Thank you.

My pleasure Jenny. I always learn a lot when I write posts.

We often think issues like this are ‘complex’. That’s true in the details but the point is to get some clear line of sight that goes directly to what matters. I don’t always get things as clear as I’d like, or focus on the most important aspect of an issue, but it’s always worth the effort.

Regards,

Puddleglum

The poverty of morality? The poor, the middle class declare, will always be with us. In 1935 Labour won 48% of the vote on their way to victory, and in the decisive 1938 election they got 55% of the vote. But in 1938 – despite the obvious success of Labour’s program, despite the obvious failures of capitalism, despite the manifest lack of undeserving poor – 40% of New Zealanders still voted for National. Given the lack of a crisis approaching the Great Depression, is it hardly surprising so many of the middle class wish to blame the poor, given how many were still willing to do so in 1938 against all the evidence? Yes, the poor might always be with us. But so will the heartless pharisees of the middle class, self-appointed moral guardians of the nation.

Hi Sanctuary,

Thanks for the comment and the historical reminder. I agree. The rhetoric about how the poor need to be closely managed and punished when they show character defects goes back an awful long way. I read something recently on the debate over the Poor Laws in the UK at the start of the 19th century. It was the strangest feeling to read almost exactly the same phrases about how, without harsh consequences, the poor are unlikely to overcome their inbred indigence and work to pull themselves up. How, unbelievably, the provision of poor houses was opposed because it amounted to rewarding such indigence and moral laxity, etc., etc..

This battle is centuries old – which is why it is vital it keeps being fought.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Look you’re right – but the pernicious climate engendered after the Mother Of All Budgets must not be allowed to recur, and in an election where the left clearly needs all the help it can get to overcome some poor leadership calls and dire polling, it was a huge ask for Jacinda to jeopardise the momentum of a crucial week in support of a principle that while clearly valid, as this article maintains, is hard to argue, especially when you’re on the back foot. So sorry, the greater good held sway and Metiria’s self-evisceration was a cruel accident of timing.

Clearly (thanks Geoff Simmons) we’re heading for a broad acknowledgement of the need for a UBI – at which point MSD box-tickers will hold a lot less sway. I can see that principle gaining ground under Labour, and it would be idiotic at this early stage of a campaign that depends on the return of the self-righteous from the fringes of National and NZ First to try to hang your hat on the justifications for what is still widely considered, however misguidedly, to be fraud. The process of public enlightenment won’t happen overnight, and won’t happen at all if National is returned to power.

So occasionally, for the greater good, you need to swallow a rat.

Hi Peter,

Thanks very much for the considered and nuanced comment.

I thought quite a lot about that argument – ‘purity’ vs. ‘realpolitik’. But I think that particular ‘binary’ overstates the starkness of the options here. I realise that Ardern had only been leader for a few days. I also realise the wariness over being on the wrong side of a backlash in terms of election campaign strategy. That’s partly why I asked whether or not the ‘idealist’ foot would ‘fall’ from Ardern on this issue at some point (something I still hope will happen, but rather forlornly).

Ardern could, for example, have excluded Turei but emphasised that she will make a priority of working to fix our welfare system so that it is not so punitive – that is, she could have stood alongside the stand Turei took while still looking like she did not condone law breaking. But she didn’t.

My concern is that an opportunity was lost at this moment. And that opportunity is not just about addressing the damage that has been done to so many people and continues to be done to this day (though obviously that is a major missed opportunity). It’s also about the lost opportunity to demonstrate distinctive leadership in support of what, I presume (hope), Ardern also believes.

And I don’t think that arguing for something you believe, and have thought carefully about, is ever as ‘hard’ as you suggest. It is hard, of course, if you don’t believe in it or haven’t thought carefully about it.

There’s debate over whether Labour should tack to the centre or tack left. But what probably matters more than where on the political spectrum Labour attempts to position itself is some sense that it does indeed stand (consistently) for something. That means being distinct (e.g., from National) but it also means having convictions that can be clearly articulated (because you believe in them and have thought about them a lot).

For me, the missed opportunity was partly about missing the opportunity to show conviction. That’s why I’m critical of the ‘silence’ of Ardern over just what she found so inappropriate about what Turei had done and said that meant she was disqualified from being a Minister in a Labour-led cabinet. This ‘silence’, so far as I can see, was at one level an attempt to have her cake and eat it too – distance herself from the criticisms of Turei in the media and, perhaps, the public’s mind while not explicitly saying that she finds it reprehensible and totally inexcusable that any beneficiary might lie about their circumstances (and so not offending leftists who are sympathetic to Turei’s stand).

At another level, though, it struck me as a signal of passive assent to the idea that beneficiaries must be harshly punished for any ‘stepping out of line’ behaviour. To the idea that they must remain the purest of the ‘deserving poor’ for the taxpayer to deign to offer any help. Passive assent does not demonstrate conviction, let alone leadership – but, because of its passivity, it allows others to take it as ‘conviction’ to whatever they wish. In the present context, far too many are going to fill that space with the notion that Ardern is comfortable with the current punitive ways in which we ‘manage’ beneficiaries and the poor.

And, if I’m right, then that means any Labour-led government would have in effect painted itself into a corner from which it will never have the electoral backing to address this gross injustice. By not putting a stake in the ground at this moment Labour has made it almost impossible for itself to put that stake in the ground in the foreseeable future. And that’s a tragedy. Some in the Labour Party may be ok with that – either because they agree with the punitive approach or they think it worth trading off against what they foresee as other potential ‘gains’. But, at the very least, Ardern needed to make that clear one way or the other.

In one sense, it is less the decision to exclude Turei from Cabinet that disappointed me but the fearful, ambivalent and unexplained way in which it was done. Ardern had to say why Turei was unfit to serve in her cabinet – not just leave it to others to divine her reasons.

Once again, thanks very much for taking the time to comment. These issues really matter and, above all, we need to talk about them until this boil is finally lanced.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Pingback: Political Roundup: In defence of Metiria Turei -

Pingback: Maori, woman, mother: #IamMetiria – Leonie Pihama

Thanks a lot for this, I really enjoyed reading i and learnt a lot. Enjoyed your perspective.

Hi E.Opla,

Thank you for taking the time to comment. I’m glad you found it worthwhile to spend time ploughing through it 🙂

Regards,

Puddleglum

Impressive. Thank you.

And thank you Kathryn for the kind comment. Always appreciate feedback – the good, the bad, but not so much the ugly 🙂

Regards,

Puddleglum

This has been parked in my inbox for a while and Ive just read it. Thanks for the outstanding exploration of the issue. It has clarified my concern about its significance but doesn’t ease my huge regret about her timing and the consequential runaway results.

Hi Dave,

Glad to hear you found the time to have a read (and to make a comment).

The consequences have been regrettable, at least in the short term. But I tend to the view that all societies are in a constant struggle with the truth about themselves. Many interests are at play and those interests best able to exert themselves at any moment (i.e., those interests that dominate the institutions that determine immediate outcomes) will typically win the day – though not necessarily the future.

Regards,

Puddleglum