It is often said that those who “Live by the sword, die by the sword“.

It might also be said that those politicians who, less excitingly, live by portraying themselves as ‘pragmatic’ and ‘non-ideological’ will, in the fullness of time, die by the same means.

John Key has always known this:

So yes, he says, the day may eventually come when his proudly worn labels of pragmatist and non-ideological get reframed in the public eye as wishy-washy and doesn’t believe in anything.

“In the 24-7 blitzkrieg of the media, eventually they’ll tire of every politician, and I’m not unique in that regard. So the things they like about me, I think you have to accept, over time they won’t like so much about me.”

In what could turn out to be the truest words to escape John Key’s mouth, he may well have written his political epitaph – and it looks like “over time” is increasingly now.

Key’s exit, when it comes, will be just as he describes: His perceived strengths will become his perceived weaknesses.

That exit may be personally managed by him as he sees the omens gather; it may result from ‘stepping aside’ (or being ‘nudged’) when a leadership challenge emerges; it may result from electoral loss. Through whatever means, it will be because his ‘pragmatic’, ‘non-ideological’, ‘relaxed’, ‘joke-cracking’, ‘hokey-dokey’ persona will be reinterpreted negatively – “over time“.

Key’s decline, however, also acts as a morality tale about the changed New Zealand of the last 30 years. In the end, John Key is a product of his time. His flaws are flaws that are remarkably synchronous with those of New Zealand society. How could it be any other way?

Not only does Key’s strategy not ultimately work “over time“, but also the corresponding strategy at the national level does not work.

But, first, there’s the fascinating details of how Key’s recent troubles highlight these flaws at the personal level.

The current crop of seemingly endless incidents of forgetfulness and selective ignorance about his electoral business, voting record and portfolios (including the Prime Ministership) have accumulated so rapidly that they may well signal the coming of the end for Key.

It’s worth remembering, though, that political deaths can sometimes be as prolonged as those of opera heroines. There may yet be a period of increasingly embarrassing revitalisations of Key’s supposed fortunes before our collective patience wears to the point where almost all of us start tapping our fingers and begin glancing at our political wrist watches.

In fact, shirt cuffs are already being pulled elbow-wards and the glances at the watch are becoming less and less discreet:

Yet again, the Key-led Government finds itself in a rut. If it’s not one thing, it seems, it’s the other. The spying scandal; the Christchurch school closures; and a debate over water rights that has kicked the partial asset sales programme into next year.

A Roy Morgan poll out late this week was, according to National Party pollster David Farrar, “sober news” for the party.

Ditto, from Audrey Young:

Few people believe John Key is actually dishonest but more people now believe he is too casual, too trusting of departments, too sloppy in his oversight and too forgetful.

I’d challenge one part of that claim from Audrey Young – “Few people believe“??

There was that poll prior to the last election that found some 34.9% of New Zealanders believed that Key was “most likely to bend the truth” compared to Phil Goff (26%) and “[a] further 21.3 per cent said both would lie“.

So, according to the poll, over 56% of New Zealanders believed Key is potentially dishonest. Somehow, I don’t think those numbers have improved, for Key, this year.

And again, from Vernon Small:

John Key and his Government have endured a slew of such moments unscathed, but the latest alignment of the planets may be the worst so far, and the latest polls are already beginning to look soggy for National.

The killer mix for every government is a cocktail; unpopular decisions, an electorate tiring of the same old faces and a loss of perceived competence.

Even without the Dotcom cluster-bomb, there has been a catalogue of confidence-sapping events for National; among them the class sizes U-turn, the postponement of the asset sales programme and, most recently – and perhaps long-term the most damaging – the restructuring of schools in Christchurch.

And, yet again, from Patrick Smellie:

… as the endless, dreary scandal morphed into arguments over a top-secret, undistributable GCSB PowerPoint slide and a meeting which may or may not have been filmed, Key’s personal performance and preferred leadership ratings have just kept sinking.

That’s dramatically demonstrated in the TV3 poll this week which showed his performance rating, while still respectable at about 50 per cent, has slumped from above 70 per cent a year ago.

The direction of travel in other key [pun?] measures, including whether the prime minister is perceived as honest, are also heading south. It’s standard second-term stuff, but it also shows the impact of crises on reputations.

…

Put simply, the decline in Key’s personal ratings is a reflection of a dawning view that a politician who once seemed quite trustworthy to many may no longer be so.

Apart from one small correction – Key’s preferred Prime Minister rating is now at 40%, not the “still respectable at about 50 per cent” that Smellie incorrectly reports – the claim is the same – a political tipping point has been reached.

Let’s take a look at one of the recent kerfuffles, as a random example (we’re a bit spoilt for choice, really): Key’s knowledge of GCSB involvement in the ‘Dotcom case’.

According to John Key in his correction of an earlier answer to an oral question in Parliament (the video of the correction is available in this link):

“A subsequent [to Key’s original answers to oral questions] review of all the information held by the GCSB found that on February 29, I viewed a presentation that was not related to the Dotcom file, during a visit to the bureau,” he said.

“I am advised that the talking points to the presentation included a short reference to the Dotcom arrest as an example of co-operation between the bureau and the police.”

Further:

He [Key] said the cover slide used during the February 29 presentation was a montage of 11 still images, one of Dotcom.

“Neither the presentation nor the talking points were provided to me in hard copy.

“Neither the director of the GCSB or [sic] me recall the reference to the Dotcom matter during the visit, but I accept that well [sic] have been made.

“I wish to make it clear that I was not informed by the GCSB on its role in the Dotcom matter, nor any issues of potential illegality until Monday, 17th September,” he said.

Now, it’s hard from this brief statement to determine quite what the presentation was ‘on’ – although apparently it was not just on the Dotcom arrest. That arrest happened on January the 20th, 2012, as this very useful Listener timeline indicates.

But here’s a presentation about – possibly amongst other things – cooperation between the GCSB and the Police. A talking point and a cover image both concerned Dotcom.

Yet, despite the image and talking point, that presentation seems, for Key, not to have amounted to being informed about the GCSB’s “role in the Dotcom matter“. This despite the ‘Dotcom matter’ – according to a talking point – being used as “an example of cooperation between the bureau and the police“. So, logically, the ‘role’ of the GCSB in the arrest is mutually exclusive with the GCSB’s cooperation with the police over the arrest?

Again, the presentation – or at least a ‘talking point’ (what does that mean? Was it actually talked about or wasn’t it?) – that included the GCSB cooperating with the police in the Dotcom arrest is quite different from their ‘role’ in that arrest?

OK.

Let me throw John Key an argumentative lifeline: The ‘role’ of the GCSB actually means, in Key’s mind, the particular activities underpinning the ‘cooperation’ as opposed to the bare fact of cooperation.

While cooperation ‘may’, according to Key himself, have been briefly alluded to in the presentation, there was, let’s imagine, no mention of what that cooperation involved. And, at some abstract logical level, ‘cooperation’ does not amount to substantive discussion of a ‘role’.

There was also presumably no curiosity on the overseeing Minister’s part as to what that cooperation involved (which would then have led to discussion of its ‘role’). In fact, so little curiosity or attention that the mention of Dotcom slipped Key’s mind (along with that of the GCSB Director, apparently).

All of this despite the very recent (at that point in time) public – and political – salience of the Dotcom arrest.

One of the problems for politicians putting forward the ‘forgetfulness’ defence, however, is that memory depends, crucially, on paying attention:

Classic psychologists such as William James stated long ago that ‘we cannot deny that an object once attended to will remain in the memory, while one inattentively allowed to pass will leave no traces behind’ .

Key’s claim of forgetfulness rests on the supposition that he was either not paying sufficient attention to a security briefing or that the GCSB were extremely ‘thin’ in their coverage of their involvement of the Dotcom case: Basically, they simply told their Minister “We cooperated, nothing else to see here, move right along”.

Both explanations look unflattering: The first solely for Key; the second for the GCSB (given their crucial involvement in Dotcom’s arrest) and for both Key and the GCSB, (given the spectacular currency of the case).

Okey-dokey – but, given that, I’m not sure my lifeline helps Key much.

Then there’s Dotcom’s image and the nagging questions that follow from what we’ve been told, and not told, about it:

- How big was the Dotcom image on the cover slide relative to the other 10? According to Key, “The cover slide was a montage of 11 small images, one of which was Dotcom” so, presumably, they were all equally vying for Key’s attention. Did he remember any of these ‘small images’ and, if so, which ones? And, what were the other 10, and should we know? (After all, they could be images of Dotcom’s mansion, or the giraffes loping around his property, etc. – not actually of Dotcom himself.)

- Did John Key not think to himself when he saw the cover slide – ‘What’s Dotcom doing in a GCSB presentation given I don’t recall ever having heard mention of him in my previous GCSB briefings, or, in fact, ever, by anyone up to a few weeks ago?‘ Surely the GCSB didn’t have anything to do with that arrest, did they? Is the GCSB just trying to be sexy and topical – just like me when I tell jokes??‘?

- Did John Key recognise Dotcom’s image? Presumably not or, at least, not enough to enter memory. It seems that Key mustn’t have been paying much attention to the news, either, at the time.

- How many people were hunched over the laptop, and who was pressing the arrow keys? Can they confirm how much time was spent on the cover slide and any other slides during which mention of Dotcom may have occurred? Was John Key provided with a clear view of the laptop? Could they stop him from cracking jokes long enough to let the briefing happen?

This is Key’s problem: Nothing he says about just about anything at the moment bears scrutiny. Each point Key makes sounds so unlikely or so self-damning. It descends into farce without external help from those predisposed to be critical of him.

And then there’s Key’s strangely revealing comment about his joke-cracking:

During a press conference at Auckland airport this afternoon, Mr Key said he made jokes about “everything from water to ACC” as well as Dotcom.

He said he would not cut back on the jokes he made.

“Give me a break. I go out there and speak and entertain thousands and thousands of people every week.

I can be straight-laced and completely boring if you want me to be but I don’t really see how that’s going to do much.”

Key jokes about “everything from water to AAC” (perhaps “AAC to water” would have been more alphabetically apt). He would “not cut back on the jokes he made“.

And why is he such a joke-cracker? Because, he goes “out there and speak[s] and entertain[s] thousands and thousands of people every week“.

Now, I agree that every successful politician is also an adept entertainer on occasion. The art of oratory is about captivating an ‘audience’ as much as anything.

But – and here’s something I haven’t heard from a Prime Minister before – successful politicians don’t usually characterise what they principally do when they’re giving speeches as ‘entertaining’ people.

That candid self-characterisation was followed by the even more revealing comment that while he could be “straight-laced and boring” in public he didn’t “really see how that’s going to do much“.

Does he mean this? A Prime Minister giving speeches without jokes isn’t “going to do much” (except sound “completely boring“)? What does he think his speeches are all about ‘doing’, then?

Almost without pause, Key’s oddly unfortunate memory continued to bedevil him with the comment about how he voted on the liquor purchase age.

Here is how MPs voted on the bill (there were two votes). John Key voted (1) for the split age (18 in on licences; 20 in off licences); and, (2) to keep the purchase age at 18 everywhere.

This is what Key said about how he voted:

After hearing on Wednesday that most voters in a new poll thought the age should have been raised to 20, Mr Key said he agreed with them.

“That’s one of the reasons I voted for it to go to 20 – in line with what the public thought,” he told media.

“[I]n line with what the public thought” (past tense)? What did the public think prior to the purchase age vote? Well, there was this Herald Digipoll at the end of June, if that’s any indication:

When asked by the pollsters to choose between three options for the minimum age to buy alcohol, 58.6 per cent preferred 20, which was the age before a law change in 1999. Only 14.5 per cent wanted the status quo of 18, while 25.7 per cent wanted a split age.

“[I]n line with what the public thought“?

They ‘thought’ – overwhelmingly – that it should go to 20. Only 25.7% supported Key’s original position in favour of the split age option. A mere 14.5% supported the option he finally voted for (18, the status quo). Yet, John Key claims he voted “in line with what the public thought“?

And this is what Key said – at the time – in explanation for why he supported leaving the age at 18, once the split age option had been defeated:

“I felt that moving it to 20 across the board didn’t make sense,” he said.

“I think we’re seeing a lot of pre-loading, youngsters getting cheap alcohol and drinking a lot before they go to a licensed environment… I wasn’t convinced the real harm was happening in that licensed environment.

Key thought that “moving it to 20 across the board didn’t make sense“, yet he agreed with a new poll that showed most New Zealanders thought that Parliament got it wrong by leaving the age at 18.

The poll wasn’t about the split age option: it simply asked those polled whether or not MPs had got the vote right. Interestingly, 57% of those polled thought Parliament had got it wrong – pretty similar to the 58.6% in the Digipoll.

Some 40% said they got it right – which is about the same as those who preferred 18 and those who wanted a split age in the Digipoll. Key’s voting is obviously “in line with” the 40%.

Yet, not according to him.

What’s going on?

Key apologised for possibly misleading people by not inserting ” ‘at an off licence'” after his comment that “That’s one of the reasons I voted for it to go to 20 [at an off licence]- in line with what the public thought – but Parliament didn’t vote that way“.

Notice also that he dug himself his own hole here. He was not asked how he voted. He was told about the poll. Almost reflexively he seems to have wanted to show that he sided with the popular view during the vote.

So, even if he ‘mis-spoke’, what he did ‘spoke’ was still harmful to perceptions of his character – he wanted to associate himself with the ‘cool gang’ and appeared, on the hoof, to reinvent his voting behaviour as an ‘alignment’ with public sentiment, despite his clear view that it “didn’t make sense” for the age to be 20 “across the board“.

So here’s another example where what John Key says, at best, reflects a complete lack of care over what he’s saying. At worst, of course, it could be called lying. But notice that the accusation doesn’t have to be that contestable or controversial to damage Key’s public persona. The ‘relaxed’ Prime Minister can, “over time“, very soon come to be seen as the ‘lax’ Prime Minister. Here’s how that happens.

As both of these examples (the GCSB issue and the alcohol purchase age vote) show, John Key has the obvious habit of being logically unconstrained by what he has previously said or done. He is, to put it simply, habitually logically inconsistent in his utterances. His statements dart about like little fish flitting away from a predator or, simply, the light.

And it doesn’t matter whether that inconsistency is part of some cunningly devised deceitful strategy or just part of who John Key is (in fact, the latter may be worse). What it demonstrates, quite literally, is a lack of integrity. They reveal an impulse to the most convenient positioning in the current moment, despite any supposed general social obligation to consistency.

The word ‘integrity‘ comes from ‘integer’. It refers to someone who is, in practice, consistent – integrated, whole – across time and situation both in the way they act and in what they say. Such people operate according to principles or values that allow them to act ‘with integrity’, irrespective of the context:

The word “integrity” stems from the Latin adjective integer (whole, complete). In this context, integrity is the inner sense of “wholeness” deriving from qualities such as honesty and consistency of character. As such, one may judge that others “have integrity” to the extent that they act according to the values, beliefs and principles they claim to hold.

I pointed out some time ago that, in the modern world, we often take someone’s presented personality as a rough-and-ready immediate ‘stand-in’ for their character – and that means we often misjudge character. I also pointed out that John Key’s character would only become clear – to the majority – “over time“.

Here’s how I explained it then:

Here’s a straightforward account of the difference from Alex Lickerman.

Notice that, while [Stephen] Franks argues that humans have a great ability to judge character, it would be truer to say that we have a great ability to judge personality. As Lickerman points out,

Personality is easy to read, and we’re all experts at it. We judge people funny, extroverted, energetic, optimistic, confident—as well as overly serious, lazy, negative, and shy—if not upon first meeting them, then shortly thereafter. And though we may need more than one interaction to confirm the presence of these sorts of traits, by the time we decide they are, in fact, present we’ve usually amassed enough data to justify our conclusions.

Character, however, is quite different:

Character, on the other hand, takes far longer to puzzle out. It includes traits that reveal themselves only in specific—and often uncommon—circumstances, traits like honesty, virtue, and kindliness. Ironically, research has shown that personality traits are determined largely by heredity and are mostly immutable. The arguably more important traits of character, on the other hand, are more malleable—though, we should note, not without great effort. Character traits, as opposed to personality traits, are based on beliefs (e.g., that honesty and treating others well is important—or not), and though beliefs can be changed, it’s far harder than most realize.

That’s the personal level.

But, while it is important to come to some sense of John Key’s character, given his status as Prime Minister, there’s a broader and more interesting issue at stake.

It is an old saw that we get the government we deserve … and the politicians. To some extent, our politicians manifest our society and its associated values and attitudes. Since John Key entered the adult workforce – almost in lock step with the start of Roger Douglas’ economic and social reforms – there has been massive social and cultural change in New Zealand. Key has ridden, with some success, that wave of change.

The neo-liberal reforms that began in the mid-1980s not only involved the deliberate engineering of major economic and social structural changes but also the legitimisation of sets of attitudes that would probably have seemed both daft and entirely unacceptable to earlier generations of ‘ordinary Kiwis’.

That had consequences.

One telling statistic – as summarised by Robert Gregory (beyond the paywall) – is that:

The rate for fraud increased from just over 20 recorded offences per 10,000 population in 1962 to just under 100 per 10,000 in 1995. The Ministry of Justice has predicted that “the number of recorded offences will continue increasing for most offence types…[and that]…Fraud in particular could undergo considerable growth, especially given technological advances and increasing awareness of the extent of offending”.

Largely in response to white-collar crime excesses of the pre-stock market crash of 1987, the government in 1990 established the Serious Fraud Office (SFO). This is a government department charged with investigating serious or complex fraud in both the public and private sectors.

The gnawing question – at least for some – has been whether or not the neoliberal reforms that began in New Zealand in 1984 have changed the way New Zealanders think about the world, their obligations to each other and their character in general.

Similar questions have been raised about the impact of the Thatcher years in the United Kingdom. Andy Beckett in The Guardian begins his opinion piece with this observation:

In 2006, the year before the financial crisis started, BBC2 broadcast a luxurious adaptation of The Line of Beauty, Alan Hollinghurst’s heady novel about rich Britain in the mid-80s. In the Observer, Tim Adams, who had been a young adult in the heyday of Thatcherism, wrote a perceptive essay about the feelings the programme and book provoked. For some of the people who had read the novel on his recommendation, “certainly those a few years younger than me,” he wrote, the “moral shifts Hollinghurst was concerned with no longer had the power to shock. They had grown up with nothing else but 80s values.” Adams concluded: “The point about the 80s is that they have never finished.”

Here’s more from Adams’ “perceptive essay“:

Lots of things changed in the 1980s, the decade which decisively formed the Britain in which we now live, but the most striking of them was the way in which market forces inveigled their way into everything.

After about 1983, it seemed, you no longer found a decent place to live, you invested in property. Ideas often seemed worthwhile only if they could be exploited commercially: politics became an extension of marketing, books became important if they were in the bestseller lists, and there was a general feeling that if someone had made a lot of money, he or she had to be taken seriously (cue Richard Branson, Madonna). The option, a refusal to go along with some or all of this, was increasingly a kind of redundancy, not quite an opting out, but a sense, somewhere along the line, that you were a sucker.

And some more:

I had started to see friends of mine, people who had not been out of jeans and T-shirts for three years, wearing shiny suits and ties. In the bar, with their hair combed, they would be clutching folders of promotional literature and talking excitedly about the promises of various investment banks. I had no real idea of what an investment bank was, beyond a vestigial sense that it was almost certainly the enemy of the people.

…

I thought a particular mate of mine was joking at first when he told me one night he was planning to be a chartered accountant [A decision, as it happens, made by John Key almost at the same time on the other side of the planet.]. Course you are, I suggested, with your double first in English literature and your devotion to the Ramones. And then he started talking about the importance of professional qualifications and how the real money these days was in futures and this was a stepping stone and you had to think of the housing market and it was all a laugh really and he would have retired by the time he was 40 to write his novel. Forty, I’d thought, crikey.

Those of us old enough to be adults then can probably cite similar surreal moments of dawning awareness about what was going on. I was on my OE when the 1984 election happened. On my return late that year I found university friends who had, until then, shown no interest in money beyond how much cash-in-pocket they had for Friday night, start telling me about how much they’d made off their shares (??) in the ‘last quarter’ (quarter of what??).

I also remember a friend who, with a ‘lesser’ qualification than mine, left university and, in her first year as a financial trader in Wellington, gained a bonus almost as large as my annual starting salary (with a ‘higher’ qualification) in a professional job. It was an odd time for a New Zealand that had never seen anything like it.

Which leads us back to the fundamental question: How much have we – as a society and as people – changed?

Are we now more likely than we were three or four decades ago to go for our own self-interest even if it means walking over others? Have we become less likely to worry about acting with integrity or is falling for the allure of the immediate advantage now just assumed?

Unfortunately, there’s no research directly on these kinds of questions. There is some, however, on what people say they believe in and what they claim to believe is ‘good’ behaviour.

In one study, those attitudes have been tracked from around about 1990. The study concluded that, “This review has found no paradigmatic shift in thinking about social citizenship rights in New Zealand since the implementation of neo-liberal reforms from 1984, although some significant changes are evident.”

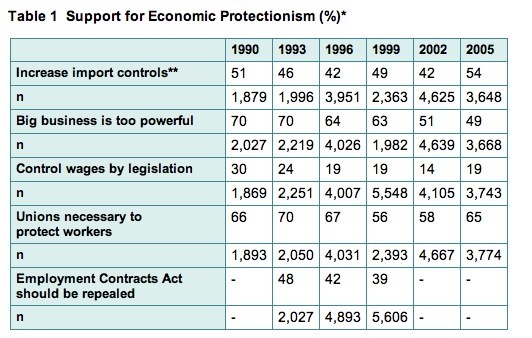

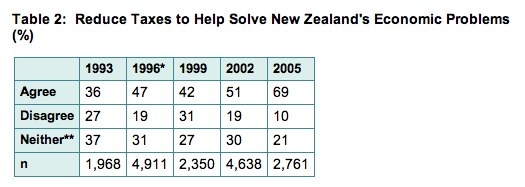

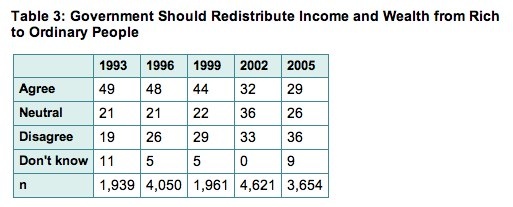

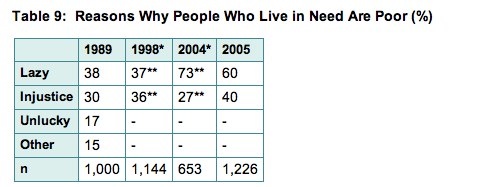

Those “significant changes” are worth looking at. Here’s some of the tables from the linked article (I’ve selected some of the bigger changes):

Source: Humpage (2008). Neo-liberal reform and attitudes towards social citizenship: A review of New Zealand public opinion data 1987-2005 – Ministry of Social Development

Source: Humpage (2008). Neo-liberal reform and attitudes towards social citizenship: A review of New Zealand public opinion data 1987-2005 – Ministry of Social Development

Source: Humpage (2008). Neo-liberal reform and attitudes towards social citizenship: A review of New Zealand public opinion data 1987-2005 – Ministry of Social Development

Source: Humpage (2008). Neo-liberal reform and attitudes towards social citizenship: A review of New Zealand public opinion data 1987-2005 – Ministry of Social Development

Unfortunately, the study did not (or could not?) go back to the 1960s and 1970s (or even the early 1980s) so it represents changes within the neoliberal reform period rather than providing a ‘before and after’ snapshot.

Nevertheless, the changes concerning the power of big business, a role for government in wage-setting, increasing support for tax cuts, less support for redistribution and an increase in the belief that people are poor because they are lazy reveal a pattern consistent with a change toward neoliberal values in, at least, the economic realm. Support for public health and education provision remained fairly steady.

[There are other studies by Louise Humpage linked to this research which provide more comprehensive and qualitative findings – links are on her university homepage.]

The question of whether or not New Zealanders have become more individualistic, self-interested and, therefore, tolerant of those qualities in politicians I’ll leave for you to decide.

Personally, I tend to the ‘Jesuit’ view.

Just as, apparently, Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit educational system, said “Give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man”, I’d guess the same applies to radical reform of the economy.

Change it radically and rapidly and then sit back and watch the population’s attitudes gradually fall into line. Ensure there’s no ‘back-sliding’ for at least 15-20 years and you’ve got the next generation thinking your new regime is simply normality.

I suspect that what the 1980s did was to encourage the attitude that you’d be a sucker not to focus your efforts on opportunities for yourself, with their promise of immediate, short-term gains. At the individual level that encourages people to adopt a self-interested pragmatism.

At the political level it may also encourage people to support policies that coincide with that view and are thought to enable it and to demand it from others (e.g., lower taxes so you can do what you will with more take home pay; harsher benefit conditions both to reduce the need for taxation and to discipline others to respond more to ‘market signals’; reduction in the rights of unions so that individuals have to go it alone – just like you’ve supposedly done – etc..).

Even ‘good’ people who would never publicly subscribe to self-interest as a primary motivation will find themselves rethinking their preferred values in order to survive materially, keep their job or whatever. At that point, cognitive dissonance would kick in to push people’s thoughts towards justifying their own necessarily self-interested actions.

As I put it in a previous post, we will come to believe what we need to believe.

If there is such a mythical beast as ‘Waitakere Man‘ (complete with a penchant for choral singing), then, attitudinally, he’s the residuum of the effects of the 1980s reforms on working class people: The lucky survivors who – to combat the dissonance – had to explain why they were ok while so many others suffered.

The answer was given to them by the right – it’s because you worked hard (not being lazy on the dole/benefit), deserve what you earn (aka ‘tax cuts’) and have been practical and pragmatic in your choices (no degree in gazing at your own navel or community education courses in macrame for you). You’ve got down to business, taken responsibility for yourself and ‘got stuck in‘.

[Interestingly, Chris Trotter’s account of ‘Waitakere Man’ is remarkably consistent with the findings on attitude change reported above – right down to still supporting health and education.]

Whether or not my speculations are correct they bring us full circle.

The so-called pragmatic, non-ideological positioning (and re-positioning) of John Key is not only fully consistent with the spectacularly self-interested individualism enabled by the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s and 1990s (expressed most obviously in the financial sectors), it may well also be reflective of a broader shift – of necessity if not, perhaps, completely in expressed attitudes and values – towards self-interested pragmatism as the as the way to get by in today’s New Zealand.

Pragmatism has its resonance for many New Zealanders – and probably always has. But it also has its dark side.

At its rawest, it is simply a concern for what works and, more specifically, what works right now. It is often narrow in vision and is driven by the desired ‘end’ and immediate circumstance. It can result in behaviours (and beliefs) that change like a chameleon’s colour from setting to setting.

It’s principally about survival. But there’s a funny thing with the ‘value’ of survival.

Aristotle pointed out that happiness is something best not pursued directly – it’s a by-product of doing other things.

Well, survival is the same. If it happens, it happens through commitment to something other than survival.

The reason for that is simple: The future is uncertain; and the road to the future is complex and not under anyone’s control.

That means that there is no such thing as a ‘survival instinct’ (at the personal level). All there are are instincts for other things (e.g., to avoid snakes).

Paradoxically, while ultimately there is no guaranteed formula for survival, a sure and certain way not to survive is to live your life moment-by-moment with the aim of preserving your ‘self’ – which is to say, to be self-interested, to put your personal goals and ‘aspirations’ above all things.

The only chance any of us have to ‘survive’ in our social world is to hold to some values, some principles that will constrain our moment-by-moment options. Being honest, for example, is a constraint – but it’s also recognised as being ‘the best policy’ and the wisest long-term strategy.

The same applies for New Zealand as a whole. There’s no such thing as a strategy of brute survival in the modern, global world. We have to hitch our wagon to some clear values that, in some circumstances, will constrain us (we might, for example, miss out on that film production because we value the rights of workers, on that trade treaty because we value human rights or the environment).

John Key’s political and verbal strategy, by contrast, is constantly to edit and re-edit his accounts of his own behaviour and beliefs in an attempt to secure short-term advantage (and acceptance). As I’ve argued, such a ‘pragmatic’ approach lacks – almost by definition – integrity (and I mean this in a technical as much as a moral sense).

Key’s approach has also been called ‘non-ideological’ and ‘pragmatic’ but it simply amounts to self-interest with its ultimate valuing of self-preservation.

That approach won’t work “over time“.

It won’t work for John Key.

It won’t work for the mythical ‘Waitakere Man’.

And it won’t work for New Zealand.

Another great essay PG. I agree wholeheartedly, even as someone who was a child of Thatcher but, for all that, sensed something wasn’t quite right. I thought the wheels had fallen off in 2008-2009 but somehow they managed to keep things going. It’s fascinating watching this all unravel. Let’s hope the next lot have the courage to take us in a different direction.

Hi Raf,

Thanks again for commenting.

Yes, it would be good if we just, collectively, came to our senses a bit and realised that we are not each going on separate trajectories but are part of a nested set of communities.

One of the things that keeps coming back to me is the sense that fear doesn’t work – yet we’re all fearful because we increasingly feel that our fellow citizens actually won’t help us if the proverbial hits the fan in our individual lives. That leads to a vicious circle of over the top individualism. I’m all for individuals but I’m implacably opposed to individualism. A country that seems to have a national slogan of ‘suck it up!’ just isn’t going anywhere good.

It probably sounds too patronising, but part of me feels quite sorry for John Key. It must have been hard being the son of a central European migrant, losing the presence of a father early in life, having to cope at school (school would have been hard here in Christchurch for someone with Key’s background – I went through a similar experience) and then devising a self-focused strategy to get him through his life.

I can understand it (self-focus/self interest) as a coping mechanism but it doesn’t work in the long run. And it definitely won’t work at the level of the country. New Zealanders need to find the strength in each other to meet the future – not act as individuals ducking and diving to try to survive while others perish.

The longer we keep giving mouth-to-mouth to this path – as seems to have happened since 2008-2009 – the worse will be the outcome.

Sometimes I think there’s a race between the end of the sustainability of the environment and the end of the sustainability of our social world. It’s a race in which, so far as people are concerned, it’s irrelevant which finishes first.

Bit of a ramble … it’s late.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Bravo Puddeglum, so very well said.

It is strange and it’s sad to have lived through such profound attitudinal change. Though there have been many such changes for the better, so much has been lost.

And now humanity and our fragile earth confronts do-or-die challenges in which the ways of compassion, solidarity, integrity, and community are the only possible solution. As things become inexorably worse for more and more of us, it seems we may not have the ability or even the inclination to learn in the time available to us.

As someone born on the cusp of the 90’s, now in a similar position to Adams’ 1987 foray into the white-collar working world some 23 years later, I am intrigued by the growth of wistful longing for the “old New Zealand”, but having never been there myself I find it hard to relate. I wonder if my 1912 equivalent felt similarly detached to the ‘Mother Country’

The economic signs are certainly there, but I think they’re only symptomatic of the greater picture. So much else has changed; the very idea that shops closed on weekends, rural families shared single telephone lines, you could smoke in flight etc is ridiculous. We are born into this century as ungracefully as our forebears in the last, still cobbling together some form of national identity while the world ticks on.

How we come to terms with this is another matter, but I suspect most New Zealanders long only for a stable government to hold the reins for as long as possible without sending the cart over the cliff, with parties like the Greens tacked on to keep the govt of the day on the straight-and-narrow as much as possible when it comes to our overarching narrative.

I remain highly sceptical that any elected body could achieve “proper change” (the kind that’s ceaselessly longed for) in the space of two terms, here or anywhere else. As the current EU crisis has shown, they’re left only to grip the predecessor’s reins and make superficial adjustments here and there, where the electorates “allow” it.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I don’t yearn for the years prior to neoliberalism. They were a long way from perfect, and downright ugly and cruel to any one who was different in any way.

And I suspect the stronger communal values and attitudes that I lament, were at least partly fuelled by a huge dose of out-group hostility, and the strictly policed social conformity of the times.

Agreed, just saying.

Those of us who were young adults in the 1970s were hardly hunky-dorey with the way things were. Some were suggesting vast changes to the status quo.

But the changes many were aiming for were about inclusion, justice, greater democratic say over the nature of New Zealand, etc..

The change New Zealand got in the 1980s, by contrast, was quite different from those hopes.

Hi Smith,

Thanks very much for taking the time to comment.

My interest is less in wistfully longing for the 1970s (or any other decade) but, rather, for what I see as the need for some viable form of collective approach to the future. Things, of course, change but that doesn’t mean that some fundamental aspects of life (e.g., social solidarity, cooperative endeavour, etc.) can’t themselves evolve and adapt.

What happened in the 1980s, it seems to me, is that the very notion that we should approach the future cooperatively, democratically and as a collective was more or less dumped in favour of individual(istic) ‘aspiration’.

That was not just some inevitable economic evolution but a deliberate re-engineering that required quite a bit of strategic ‘blitzkrieging’, behind the scenes machinations and rhetorical manipulation in order to succeed. It was a stunning social transformation to witness.

Also, what today may seem “ridiculous” about the past is not really the point. Or, it simply demonstrates the way in which attitude change is – as I argue in the post – a product of structural changes. Shops being closed at the weekends, for example, did not seem particularly ‘ridiculous’ at the time because most people understood the values underpinning that constraint on commercial activity – and agreed with those values, in general.

As for your scepticism “that any elected body could achieve “proper change” (the kind that’s ceaselessly longed for) in the space of two terms“, I’d simply say “1984-1990”. Now, it wasn’t ‘change I could believe in’ but it was certainly thoroughgoing change – even its proponents would claim that.

In some ways your comment I think reinforces my point that once the structures are in place for a generation or so the attitudes will follow, more or less obediently. That isn’t specific to you and is not meant personally – my attitudes are also a part-product of structures that existed when I was younger. It’s not a problem, just a fact (in my view).

What degree of ‘freedom’ we can get from those structures largely comes from engaging in discussion and debate with others – which is one of the reasons I’m in favour of collective decision making (i.e., democracy) in as many spheres of life as possible (including workplaces, communities, etc.). It improves our chances of carrying on into the future.

I really appreciate the points you raised – they made me think about my own position in more detail.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Great essay 🙂 Having lived through these years, I still feel a sense of unreality (I wasn’t very aware, I guess) of how profound the changes have been.

But, not all gloom. Some of the stats around attitude indicate there’s a mild comeback in attitudes- and that was in 2005. It’d be very interesting to see the data over the last 7 years.

Thanks for the read.

Thanks Rob.

I’m always a bit ambivalent about the value of attitude surveys. Yes, they can detect changes over time (especially if the same ‘items’ are used longitudinally). But it’s never clear why any changes are happening or what, exactly, they mean.

In fact, the same worded ‘item’ can come to mean (connote) something quite different from what it may have meant ten years previously. For example, agreeing with a statement that “Government should be responsible for ensuring employment is available to all” may indicate support for comprehensive state involvement in the economy (e.g., Ministry of Works style) at one point in time but ‘reduction of red tape for business’ at another.

The same goes for agreement with statements about providing support ‘for those in need’ or provision of a ‘social safety net’ – they mean quite different things today from what they used to mean, I suspect. This is why Humpage also did qualitative, focus group interviews – to unpack the ‘ambiguity’ in the quantitative findings. But even qualitative interviewing assumes people have a clear understanding of the sources of their own behaviours, etc..

I agree, though, that what people do or don’t support is always a work in progress – so, no, there’s no need for complete gloom, wherever someone stands in political terms.

Regards,

Puddleglum

I don’t think it’s a case of going back to the 70s. It’s more that we have pissed away amazing technological advances by inflating asset prices. We should have arrived at the point where social infrastructure was top class and poverty was a minor issue. We discovered ways of becoming wealthy without having to do very much….that’s quite attractive for most people. It’s created, what John Lanchester (author of “Capital”) described as, “obliviousness”, a sort of advanced “I’m alright Jack” philosophy. Not so much a worked out position, as one that simply came into existence and remained, fortified by appropriate imagery, persuasion and technical reframing of responsibility.

It’s not all bad news though, as all cycles run their course, and the supremacy of the financial economy may be running out of puff. It certainly has in the US and Europe (and did so in Japan some years ago). One must therefore be alert to new opportunities and grasp them when they arise 🙂

Yes, Raf.

I think a lot of people here have the sense that New Zealand has a unique set of opportunities but our ‘leaders’ are acting as if we have to do what everyone else does, only more so (push commodity booms for all their worth, sell off what we can, get everyone exposed to ‘market discipline’, etc.).

Where’s the sense of ‘can do’ and ‘innovation’ when we really need it? (i.e., at the level of organising our society and economy)

Regards,

Puddleglum

If a week is a long time in politics how about a fortnight?

Key has been looking for a couple of months as though he would rather be cleaning toilets than be Prime Minister. How come?

Consider that Key is pretty much our first “X-Factor” PM. By this I mean someone with some raw abilities but no experience who is fast-tracked into the limelight on the back of popular appeal rather than track record. He cannot possibly have been prepared for the reality of the job. And it is a horrendous job. Notwithstanding all their advisers and colleagues the PM is still ultimately leading the legislative and executive branches of government, the only person co-ordinating all the security agencies (police, armed forces and secret services), leading their party to electoral victory, somehow having to shoehorn in some domestic life, and all of this is done under relentless public scrutiny. Its not for the faint of heart which is why our traditional system for selecting good candidates for PM has served us (and the UK, and Australia and Canada) so well over the years. The system which John Key by-passed.

Consider that since 1960 we have had 18 elections and 12 PM’s. Just 4 of those PM’s (Holyoake, Muldoon, Bolger, Clark) won 13 of those 18 elections. Each of these politicians had years of experience in government and opposition, had risen from bank-bencher though junior Cabinet roles to senior roles before throwing their hats into the ring for the top job. This long apprenticeship gave them two things that money cannot buy: extensive experience on which to base their future judgement and, even more importantly, the knowledge that they wanted and could do the job. We have also seen many competent politicians (Birch, Cullen, English) who have worked out that their best place is at the side of a PM. And so we tend to throw up candidates for PM who can stick at the job for the long haul.

It is a brutal system of attrition that sifts out the unsuitable. You don’t necessarily like their style or their policies but you have to give our successful PM’s credit for getting the job done with relatively few stumbles. For some unfathomable reason both National and Labour have decided that now is a good time to bypass this system and we will have to endure the inevitable results.

Hi Kumbel,

Very good point. The notion of ‘apprenticeship’ is now seen as something to avoid if you can strategise your way to the top and avoid it. Even the TV show ‘The Apprentice’ is probably seen by the ‘hopefuls’ as a way of by-passing an actual ‘apprenticeship’ in business.

Brash was another recent example of the assumption that someone can be helicoptered into top jobs. What it tells me is that those doing the helicoptering (as opposed to those being helicoptered) assume they can take advantage of the lack of experience of the notional ‘leader’.

[I presume when you said “bank bencher” that was an unintentional slip?]

Regards,

Puddleglum

While monarchies have provided many examples of the eminence grise running things behind a throne occupied by a minor or a half-wit I am not so sure we have the same thing going on here. I think it is mostly an artifact of our times in which TV appeal, fame or name recognition is way more important than substance in the broad electorate. National have never struck me as having adapted to MMP and you can almost feel the yearning in that party to win an election outright at any cost. Of course there’s a risk with putting up an amateur politician as leader but National almost pulled off the electoral coup of my lifetime last year.

It’s no wonder they have such a close relationship with Sky City – gambling is really in National’s blood now.