There are many ways to gain power and leadership.

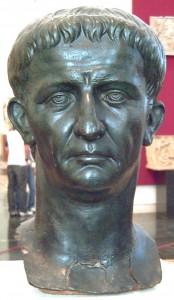

One way, famously described in Robert Graves’ novel I, Claudius, is to try your best not to offend people and stay (or be kept) out of the way of others’ machinations.

Once everyone else has ‘killed’ each other off, you’ll be the only remaining option for those capable of putting you there.

It is also apparently useful to appear ineffectual – and to stammer.

It’s tempting to see similarities between Claudius’ journey to the laurel crown of a Caesar with David Shearer’s reluctance to offend anyone, his hesitancy in interviews and the general air of vagueness and uncertainty he’s cultivated in the public’s mind, intentionally or not.

Perhaps Shearer is on to a – surprisingly unlikely – winning strategy, given Claudius’ success?

Maybe. But despite how tempting it is to draw the analogy, such a strategy is not guaranteed to succeed.

[And the word ‘Caesar’ literally means “a fine head of hair”. Perhaps not the best omen for Shearer.]

One particular advantage Claudius had that does mirror Shearer’s rise to Leader of the Labour Party, however, is that the Roman citizenry had almost no idea who he was prior to him gaining the crown.

Pretty soon, tomorrow in fact, we’ll all know Shearer – and what his potential ‘reign’ might signify – a lot better. He is due to deliver a series of speeches that will set his political course for the next while – and perhaps also set in concrete his political destiny.

Despite potentially being overshadowed by a major policy announcement from John Key, with tomorrow’s speech Shearer has the opportunity to establish a clear direction and emphasis for the Labour Party under his watch.

His best bet is to make those signals very clear. No ambiguity, fudging or attempting to have your left-wing support and eat the centrists too. No inherent contradictions either.

And definitely no contradictions in trying to appeal to both. We’ve seen enough of that.

The lasting impression from his positioning in relation to the Ports of Auckland industrial dispute that people will have gained from the media coverage, is that he tried to appeal to centre (right?) voters by saying he wasn’t taking sides and then tried to appeal to Labour’s union supporters by taking sides.

I know, as Shearer tried to argue, ‘the situation changed’.

Management showed ‘bad faith’ by sacking workers when mediation was in the offing. But that explanation for the shift in Shearer’s position just throws him back into ambiguity since it suggests that, if there was no mediation on offer, he would have stayed on the sidelines while nearly 300 port workers lost their jobs – or would he have?

Trying to please everyone by rapidly contradicting yourself is not the way to clarify your leadership direction.

The way to show leadership is to draw a clear line in the sand of the political spectrum (Yes, that spectrum remains a ‘left-right’ one. Reports of its death are greatly exaggerated.)

The art of leadership – at least for a Labour Party leader in New Zealand – is to draw that line just at the point in the spectrum where both those in the centre and those further left find themselves deciding to move a bit and put in their lot with you.

At the moment it is hard to know quite where Shearer would draw that line – or if he’s even aware of the nature of the sand in which it is drawn. But a clear line must be drawn.

The worst thing he could do tomorrow is to mark the sand with a broad, shallow and meandering line that every wisp of political wind could obscure, cover up or completely wipe out. The line has to last – preferably till the next election.

One more word of unrequested advice I have for Shearer: Claiming that the line will be drawn incrementally over the next two years and, worse still, that it will be done in some ‘problem solving’, ‘moderate’, ‘non-ideological’ way would only waste tomorrow’s opportunity.

That’s for three reasons:

First, Key remains the bearer of the Mr Moderate role – though that might change as the policy direction continues to veer undeniably rightwards.

Second, if United Future’s result at the last election is anything to go by, there are precious few voters left in the ‘non-ideological’, ‘problem-focused’, ‘common sensical’ hinterlands.

Third, Shearer is already being questioned over his reluctance to show his hand – showing it slowly, digit by digit, over the many months ahead will ensure that the answer to the question ‘Who is David Shearer and what does he stand for?’ will forever be answered by the public rolling its eyes and shrugging its shoulders.

Clear direction, once again, is the only way forward.

Shearer has one, important, ace up his sleeve at present. In having a public image of being a reasonable, likable person, Shearer could ride that reputation to shift centrist voters leftwards, even if only ever so slightly.

Successfully grasping that opportunity would first require rhetorical skills to present a more left-leaning agenda in ways that show it to be entirely compatible with many more New Zealanders’ views of themselves and their country. More crucially, it would also require a clarity within Shearer himself that that is what he actually wants to do.

That could be the real test awaiting him tomorrow – is he content to move rightwards to meet what he believes is a centre forever drifting to the right or does he have a clear enough commitment (in himself) to the correctness of a broadly left analysis of the modern world to want to pull the centre slowly back towards the left?

Just what are Shearer’s political commitments and what is his analysis? Tomorrow – I hope – we may find out.

On the assumption that Shearer does, indeed, have broadly left political commitments, there is one final point of comparison – and caution – that may exist between him and Claudius.

In Graves’ sequel to I, Claudius – called Claudius the God – he explores the theme of the balance and oscillation between ideals of Republican freedom, on the one hand, and the peaceful, but dictatorial, atmosphere of Imperial Rome. Claudius, himself, had Republican commitments but, nevertheless, found himself attempting to express them from his Imperial position (as Caesar).

If we imagine that Shearer, and the Labour Party in general, is attempting to ‘square the circle’ of his left analysis within increasingly right-wing structures, strictures and perceived realities – just as Claudius tried to ‘square the circle’ of his Republican sentiments with the realities of a set of Imperial institutions – then at some point he may find himself echoing a modern version of Claudius’ rather sad and self-defeating conclusion about his own efforts:

‘by dulling the blade of tyranny, I reconciled Rome to the monarchy’

But, then, that’s been the Labour Party’s dilemma for some time now.