The Logic of Flags

(Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ALeviathan_by_Thomas_Hobbes.jpg)

It looks like there’ll be no change to the New Zealand flag as a result of the current flag referendum.

There’s any number of reasons why that’s so. It may be that the strongest reason turns out to be the unfortunately designed alternative flag. Who knows?

But what of the arguments for changing the flag? Is their logic strong? Do they make sense?

That is, irrespective of the fact that we seem likely to reject the change, if we were straightforward, rational beings should we actually vote to change the flag?

I don’t think so.

At least not on the two main arguments offered so far.

The arguments for a flag change cluster around the idea that the national flag should show our ‘identity’ as a nation. The implicit claim is that the current flag doesn’t achieve this. It fails, that is, to show who ‘we’ are; it fails to show our independence from other nations; it fails to unite ‘us’ and it fails to distinguish ‘us’ from other nations,

Some of the arguments that underpin these claims about the flag and our identity, in no particular order, are that

- Our current flag has upon it the flag of another country and it does so because of a colonial past that we should have – and actually have – well and truly outgrown;

- That colonial past is part of a brutal imperial history that has produced massive suffering, even genocide so it’s vital we remove the symbol of that oppressive past;

- The current flag is too similar in design to Australia’s flag and so we keep getting mistaken for Australians when New Zealand athletes are at sporting events and New Zealand politicians are at international political and economic gatherings, etc.;

- Our flag should mark us out as independent, sovereign and forward looking and the current flag fails to achieve this.

In sum, there are two main arguments being put forward:

- The New Zealand flag is not distinctive mainly because it resembles the Australian flag.

- The New Zealand flag has the Union Jack on it which expresses an outdated colonial relationship and even endorsement of the British Empire.

I’ll have a look at the first of these arguments in Part I (this post) and the second in Part II (the next post).

But there are a couple of points that I will clarify first.

First, my own preference is not to have a national flag.

National flags are primarily symbols of nationalism. Whatever benefits might be argued for nationalism I think the moral ledger weighs heavily against it. If people want to feel warmth in their hearts then simple human compassion and caring are far safer bets than nationalism. And if some understandable sense of belonging and solidarity is what is needed then standing alongside those who lack power is far more constructive and worthwhile than flexing group muscles through expressions of nationalism.

It’s fine to live in peace as a people and nation but that’s as far as nationalism should be indulged.

Taken further, nationalism is always a double-edged sword – sometimes not even metaphorically.

But I accept that the flagless nation – let alone the rejection of nationalism as a pervasive sentiment – is probably both impractical and highly unlikely.

A simple banner with the name of the country clearly written upon it is apparently nowhere near spectacular or stirring enough for sporting events, political events, parades, etc..

So we’re stuck with flags.

Second, flags have always had both practical uses and symbolic meanings.

They’ve occupied some pretty instrumental and practical roles but they’ve also taken on highly symbolic functions – e.g., see here:

Flags have also been important symbols on land as well as on sea. Ships started using flags at sea to signal to each other and to harbors, often to let them know they had an infectious or diseased crew aboard. Flags are still used today to let sailors know what weather conditions await at sea. The military also made use of flags to rally its troops. In military times, capturing an enemy’s flag was considered an honorable seizure.

Although the most popular use of flags today is to identify the world’s countries, the use of national flags didn’t become commonplace until the 18th century. National flags are now used to identify each country and their symbolism.

Like the standards on the battlefield that helped identify friend and foe, national flags now help to identify ‘us’ and ‘them’.

For modern nation states that function translates to important things like issuing passports, validating the origin country of ships on the high seas (which, of course, are not owned by any country) and staking claim to territory (e.g., on the Moon, the South Pole, Mount Everest/Sagamartha).

Some flags still even have a very deliberate and widely recognised communicative function such as the white flag for military surrender and the flags used in flag semaphore.

But today most people encounter flags not for any particular practical function but, instead, in their usage in the ever-so-important ‘social’ functions of group identity and group cohesion. They are signs, amongst other things, to sing national anthems, to act with solemnity at war memorial events and to enthuse patriotically at international sporting occasions.

Like many other distinctive social group markers (a distinctive language or dialect, distinctive fashions or body markings, distinctive rituals, etc.) the practical use of flags has been largely co-opted symbolically to generate solidarity at a group – and emotional ‘gut’ – level.

It’s telling that no nation is deemed complete without its own national flag.

As the world becomes simultaneously more diverse yet more the same it’s as if we use flags to help ‘dig our toes in’ and assert our difference – our ‘identity’ and, following close behind, our sovereignty. In such a fluid, fragmentary and transient world perhaps there’s precious little else to mark us in common, as groups, or to distinguish us from each other, as groups.

Yet with the advent of nation states in the past couple of centuries the need to keep people emotionally attached to what is really an arbitrary unit of governance (the nation) – and to keep individuals attached to others (in effect, strangers) within that governance arrangement – has led to the turbo-charging of this collective symbolism.

That’s particularly true in societies that are extraordinarily diverse or have within them extraordinary tensions.

There’s a reason why flags are used and displayed ubiquitously in large ungainly states such as the former Soviet Union and throughout empires (such as the British Empire). It’s perhaps also the reason that every American child daily pledges allegiance to the flag as part of their induction into the ‘melting pot’ within which individuals spend their lives swimming around in pursuit of the American Dream.

And it’s almost certainly the same reason that every reactionary far right group cleaves strongly to – and proudly deploys – their particular national flags (or what they’d like to be their national flags) when the globalising world delivers the ‘threat’ of migrants.

In these ways national flags become employed as part of responses to the potential or perceived threat that comes from a heterogenous population. When there are fears that if a society is left to its own devices and momentum “the centre cannot hold” then, sure as eggs, you’ll see flags get hoisted higher and higher up the flag poles.

I have no evidence to support the claim but I suspect that flag waving, wearing and saluting is positively correlated with levels of heterogeneity, inequality (and unrest) in a society – whether that be economic, racial or gender inequality.

All these examples of national flag fetishism are attempts to gain emotional allegiance to various arrangements of large numbers of quite different people – either through pride and patriotism or through the darker side of that same coin; the threat of being marked as a traitor, as ‘un-American’, ‘an enemy of the revolution’, etc..

So perhaps this debate is best understood not so much as a conflict between those who want to create an independent New Zealand version of nationalism and those who still see Britain as ‘home’ (and so deny a distinctive nationalism for New Zealand) but, instead, as a further attempt to symbolically gloss – and so resolve for now – the new tensions and divisions at play in our society. (I’m ignoring the more mundane political explanations for why – at this point in time – we are suddenly voting on a flag.)

For some people, at least, the need for a new version of nationalism that we will supposedly ‘express’ in a changed national flag is reason enough to spend significant amounts of money and time considering flag designs.

It is supposedly vital in ‘uniting us’ as ‘one people’ into the future, although a word of warning: Flags have an unhappy knack of also becoming symbols of oppression and outlets for anger (flag burning, etc.) – they might be powerful symbols but if reality doesn’t conform to the symbolic hope of unity then I’m afraid the symbol is likely to come off worse in that confrontation.

Enough of the preliminaries. What of the arguments?

I’ll start with the most prosaic argument: The current New Zealand flag is too similar to the Australian flag so ‘Kiwis’ keep getting mistaken for ‘Aussies’ overseas (in sport, in the military, when backpacking with a flag on their packs, etc., etc.).

Put more positively, the argument is that the New Zealand flag needs to be distinctive – or at least distinctive enough not to be confused with the Australian flag.

Now, despite my preference for no flag it’s true that flags have their appeal.

As a child I used to pore over the pages in my encyclopaedia that had coloured pictures of the flags of the world. I was fascinated by the variety but, just as importantly, over the similarities between flags.

The reasons for the similarities were almost always a combination of history and geography. Flags, that is, for me have always been symbols that had hidden stories about a country’s past and about its relationships to other countries.

So, I have to be honest and say that I much prefer a flag to have layers of meaning (‘symbolism’) and interesting historical, cultural and geographical connections through its design. Just which of those connections should dominate (historical, cultural or geographical/environmental) is of course up for debate.

Distinctiveness for its own sake actually leaves me cold. It’s too close to what I see as a completely misguided drive to be a ‘unique’ individual at all costs.

That obsession with individual distinctiveness has led to modern trends that range from the invention of bizarrely ‘original’ names – and spellings of names – for babies (because parents want the child to be ‘an individual’) to the depressingly vacuous ‘branding’ exercises of businesses to mark out their supposedly ‘unique’ values and appeal to the market (despite, or because of, the predictable sameness of what’s on offer).

By contrast, individual people, communities, nations and peoples only make sense to me in terms of their relationships to others (other individuals, other communities, other nations, other peoples) and to their own story in that broader context over time.

For example, a name (like a flag for a nation) situates the person in a particular culture and a particular time in that culture. Beyond that it also can convey relatedness to others (e.g., a first name that is a ‘family heirloom’ or, more formally, in a surname like Erikson). It can even denote aspects of the person’s ‘place’ in a society such as their occupation – e.g., Fisher, Thatcher, Butcher, Gardener, Wainwright, Cooper, Brewer, etc. – or caste. Or it might specify location in a local geography or simply be a dazzling array of descriptors and connections:

In many parts of the world, parts of names are derived from titles, locations, genealogical information, caste, religious references, and so on. Here are a few examples:

- the Indian name Kogaddu Birappa Timappa Nair follows the order villageName-fathersName-givenName-lastName.

- the Rajasthani name Aditya Pratap Singh Chauhan is composed of givenName-fathersName-surname-casteName.

- in another part of India the name Madurai Mani Iyer represents townName-givenName-casteName.

- the Arabic Abu Karim Muhammad al-Jamil ibn Nidal ibn Abdulaziz al-Filistini translates as “Father of Karim, Muhammad (given name), The beautiful, Son of Nidal, Son of Abdulaziz, the Palestinian”. Karim is Muhammad’s first-born son.

And each person accumulates a full biography over their lifetime that the society attaches to that name: the streets and neighbourhoods they’ve lived in, the schools they’ve gone to, the friends they’ve made, the places they’ve worked, the sports they’ve played and so on.

In the same way, at least to my eyes, a flag, just like a person’s name, partly ‘indexes’ the nation amongst the (euphemistically described) ‘family of nations’. Just as for a person, a nation’s ‘individuality’ (uniqueness) only makes sense within a rich context of connections and relationships.

If a nation needs a flag then, for me, the best flag will tell both a unique story of that nation and its relationship to other nations and the part of the world to which it belongs. In that context, representing similarity with other nations is actually an important goal of a national flag.

The important design question may be less about ‘how to be different?’ and more about ‘to what and to whom should we show similarities?’

Now take a look at these flags and guess – without googling – which nations they belong to:

Distinctive Flags? [By Hansjorn: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]

The ‘answer’ is: Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. And they all share ‘Nordic Crosses’ on their flags.

It gets ‘worse’.

There are Nordic crosses in various regions of the Baltic countries, the Netherlands, Germany, the United Kingdom, Brazil, the United States, assorted other places and, interestingly, numerous ethnic groups (unofficial flags).

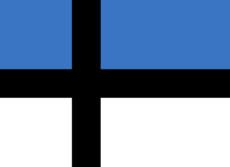

But at least Baltic countries don’t adopt Nordic crosses as their national flags even if they may have them in regional flags. Obviously, they have a much stronger desire to be distinctive:

Flag of Estonia

Flag of Latvia

Flag of Lithuania

Yet,even here, while they’re definitely different colours they do have a certain horizontal sameness about them.

To be fair, Estonia had a proposal to change its flag in 2001 and, much earlier, in 1919. At these times several alternative designs were presented:

Estonai alternative flag design 1

Flag of Estonia proposed in 1919

Estonia Flag Proposal 2

Estonia alternative flag design 3

All pretty similar and, what is more, they look ‘worryingly’ like Nordic crosses – largely because, they are:

In 2001, politician Kel Tarandaar suggested that the flag be changed from a tricolour to a Scandinavian-style cross design with the same colours. Supporters of this design claim that a tricolour gives Estonia the image of a post-Soviet or Eastern European country, while a cross design would symbolise the country’s links with Nordic countries. Several Nordic cross designs were proposed already in 1919, when the state flag was officially adopted, two of which are shown here. As the tricolour is considered an important national symbol, the proposal did not achieve widespread popularity.

Estonians consider themselves a Nordic nation rather than Baltic, based on their cultural and historical ties with Sweden, Denmark and particularly Finland.

The Baltic countries also have interesting designs for their ‘naval jacks’:

Naval Jack of Latvia

Naval Jack of Estonia

There’s a certain ‘familiarity’ about these jacks … that’s right, the combination of diagonal and vertical-horizontal crosses is very similar to the design of the Russian jack:

Naval Jack of Russia

Despite the recent not too friendly relations between Russia and the Baltic countries it seems similarity in naval jacks isn’t too much of a worry.

Then, of course, there’s that other jack:

Flag of the United Kingdom

But it may be that the people of Scotland have more to worry about when it comes to similarities with Russian flags. Here’s the Scottish flag:

Flag of Scotland

And here’s the Russian Naval Ensign:

Naval Ensign of Russia

Then there’s the green used in Islamic flags, or the pan-Arab colours used in flags of three countries that you might not expect to want to have similar flags (at least in today’s political climate):

Flag of Egypt

Flag of Iraq

Flag of Syria

And if you think the Iraqi flag was perhaps distinctively different under Saddam Hussein, think again. From 1963 to 1991 it looked like this:

Flag of Iraq 1963-1991

Yes, it does look a lot like the present day Syrian flag. In fact this flag actually became the Syrian flag the same year (before it reverted to two green stars). It all goes back to the project for a United Arab Republic.

Post-1991 Saddam Hussein made a slight alteration:

Flag of Iraq 1991-2004

The more things change …

What confusion this all must cause the inattentive and those who aren’t ‘details people’.

The Olympic Games must regularly have half its spectators thinking they’re cheering for some country other than the one that has won the medal!

More seriously, what’s the lesson here?

Pretty simply it’s that many flags look like each other for a range of reasons, from the accidental to the purposeful. That doesn’t mean that flags shouldn’t be different or shouldn’t change but it does put ‘similarity’ in flags into perspective.

It also emphasises that many, many flag designs are chosen just as much to show relationships with other countries or with common cultural origins as they are chosen for their distinctiveness.

Flags need to be different – otherwise they wouldn’t signify different countries (though there are some examples of identical flags – see next post) – But that doesn’t mean they can’t be similar.

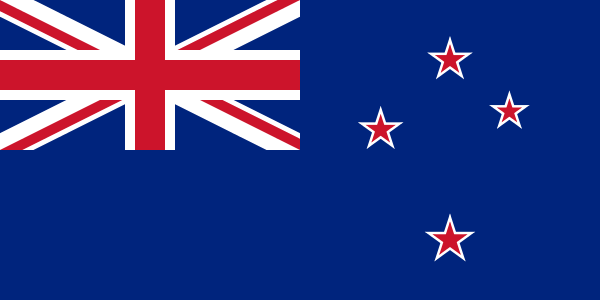

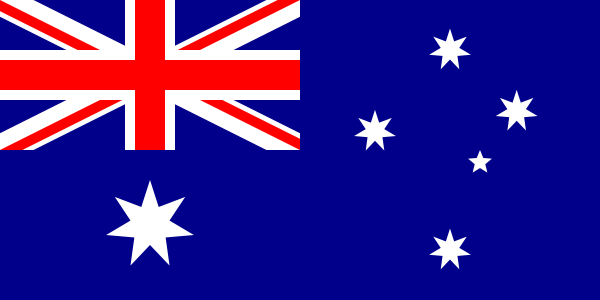

Now that there’s some perspective on this argument against similarity, here are the two ‘offending’ flags:

Flag of New Zealand

Flag of Australia

Certainly similar.

Of course it’s very arguable whether or not that similarity is greater or lesser than the similarity present in any other of dozens of comparisons between national flags – such as the Nordic cross flags, the green flags of Islamic nations, the vertical tricolour and horizontal tricolour flags of the world, etc..

Nevertheless, for some reason some New Zealanders, at least, find that similarity galling.

While other countries have obviously made a point of having flags similar to countries associated with them historically or geographically or constitutionally close to them (to show their links) in New Zealand’s case it’s apparently miffing to have a flag so similar.

I wonder how much umbrage an Estonian would take for being mistaken for a Latvian when they’re on the Olympic podium? Who knows? (Let’s face it – how many people could, unprompted, even name the three Baltic republics let alone tell their flags apart?)

The question of distinctiveness from Australia is also a bit of a strange rhetorical beast given both history and current political and economic realities.

New Zealand, as a British colony, was governed in common with Australia from New South Wales (there was actually no ‘country’ of Australia at the time) up until 1841.

Famously – and from the above link – when the Commonwealth of Australia was established New Zealand declined to become a member:

1901

The Commonwealth of Australia is established. New Zealand has declined on several occasions to become a member.

Close enough to be ‘invited to the party’ but, on the night, not keen enough finally to go. (Perhaps we were washing our collective hair?).

Which might also explain why one of the winners of the 1902 Australian flag design competition (interestingly instigated because the Commonwealth of Australia had just been constitutionally established) was a New Zealander:

A New Zealand design?

New Zealander William Stevens, a ship’s officer on the SS Taieri, was one of five winners of a 1901 competition to design an Australian flag. The successful entrants reportedly submitted almost identical designs – ‘a Union Jack in the left hand top corner, a six pointed star beneath it (representing the six federated states of Australia), and the Southern Cross on the fly’. Newspapers at the time remarked that if the people of New Zealand changed their mind and decided to join the Commonwealth of Australia all that would need to be done to the flag would be ‘to place a seven-pointed star instead of a six-pointed one beneath the Union Jack’. In fact a seven-pointed star was adopted in 1908, to represent the Territory of Papua and any other territories subsequently incorporated in the Commonwealth. Stevens and the four winning Australian competitors each received £40, equivalent to about $7000 in 2015.

But, surely, this blurred closeness to Australia is just one of those historical curiosities, isn’t it? No-one today would claim we should blend our national identity with that of Australia, let alone still contemplate union with Australia, would they?

Well, it’s interesting that one of the most revered public holidays in New Zealand goes by the name of ‘ANZAC Day’. I imagine that most people outside of Australia and New Zealand who think of ANZAC Day think of Australia and the ‘diggers’ – not ‘Kiwis’.

Perhaps we should change the name of ANZAC Day to make sure that no-one mistakes our important memorial events for Australia’s? Perhaps we should have a different day in the Calendar to further make the day distinct? Surely New Zealand soldiers need recognition in their own right and not get mixed in with the Aussies on all the important memorial occasions?

But more interesting still is that the possibility of a closer political or monetary union with Australia is a recurrent issue raised in public debate. As recently as 2011 there was more than a handful of New Zealanders willing to consider the possibility of joining with Australia:

A recent poll has found 40 per cent of New Zealanders are open to the idea of becoming a state of Australia.

Out of the 1000 people surveyed, 41 per cent said the prospect of New Zealand becoming Australia’s seventh state was “an idea worth debating“.

Respondents believed a merger would improve ease of travel to Australia, as well as our defence status.

Former Commonwealth Secretary-General [and former National Party Deputy Prime Minister] Don McKinnon has also lent his support to the cause.

That figure of 41% may well rival the proportion of New Zealanders who, in recent years, would have thought changing the flag “an idea worth debating“.

And, if you’re interested, you don’t get more New Zealand establishment than Don McKinnon (from the link above):

His father was Major-General Walter McKinnon, CB CBE, a New Zealand Chief of the General Staff, and once Chairman of New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation. McKinnon’s brothers include the twins John McKinnon, the current New Zealand Secretary of Defence and a former Ambassador to China, and Malcolm McKinnon, an editor and academic, and Ian McKinnon, Pro-Chancellor of Victoria University of Wellington, School Headmaster of Scots College and former Deputy Mayor of Wellington City. The McKinnon brothers are great-great-grandsons of John Plimmer, known as the “father of Wellington”.

It seems, then, that ‘closeness’ to Australia remains a reasonable position to adopt yet, so we are told, not when it comes to the national flag.

Where’s the logic in that?

There is, however, a common element in the flags of both Australia and New Zealand that itself has been used as an argument in favour of changing the flag. This is where things get serious …

[To be continued.]

Curiously although you viciously attack the New Zealand flag, you actually confirm that the main argument for change – alleged similarity to that of Australia – is flawed. The only other real argument is petty nationalism (or anti-British racism), and you purport to denounce that. It is a cope out to say that there should be no national flag. Every country has a flag, and ours is older than all but 15. There is no good reason for change, and many reasons to keep the flag.

Hi John,

Thanks for taking the time to comment on the post.

To be honest, my intent was not to “viciously attack the New Zealand flag” if by ‘New Zealand flag’ you mean the current New Zealand flag. And I can’t really see where I ‘viciously attacked’ it in the post. As a flag I think it’s fine in terms of design and in terms of its ‘readable’ link to historical reality.

In Part II of the post – i.e., not the one you’re commenting on here – I do argue that British colonialism and empire walked lock-step with quite horrific consequences for many people – was it to that that you were referring?

If so, I suppose it’s possible to say, along with Napoleon, that you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs but the fact remains that an awful lot of ‘eggs’ (i.e., individuals, communities and cultures) were broken as the British Empire expanded and held sway.

I also said that even if one’s overall assessment of the British Empire was positive – e.g., because of the spread of parliamentary democracy, judicial processes, the rule of law, etc. – the horrors remain on the ledger.

As for preferring that national flags didn’t exist that was, admittedly, a bit tongue in cheek. As I went on to say, it’s not a very practical position given the current way the world is organised. So, yes, a ‘cop out’ I suppose.

My overall view is pretty much in agreement with yours – there is no good reason for change.

But, where we may differ, is that I think there are many issues – not even below the surface – that suggest to me that we really need, as a country, to get very clear about the kinds of political, cultural and social arrangements we will have in the future.

If we were to have such a discussion and if decisions were made on either our internal constitutional arrangements or our general external geopolitical alignments and positioning as a result of that discussion then a ‘good reason’ for change would have been achieved. I see ‘flag change’ as a tidying up process at the end of a far more substantive change in national status – I don’t see changing a flag as an end in itself.

I also am opposed to what I think you mean by the term ‘petty nationalism’ – a kind of ‘pseudo’ or made up ‘kiwiness’ that actually doesn’t apply accurately to many – maybe even most – New Zealanders. A kind of assertive bravado and chest puffing for the sake of wanting to be seen as independent.

That was the target of my criticisms of the supposed ‘New Zealand identity’ that is said to underpin the Lockwood flag design – a kind of ‘Janet and John’ mythology of peace, multiculturalism and ‘one people’ ‘going forward’ with proud independent strides. A nice – though almost saccharine – self-image but far too vague and ‘feel good’ to be the basis for flag design.

Anyway, thanks very much, again, for taking the time to both read and comment. It makes writing these posts worthwhile when I receive comment back from the ‘void’.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Symbols are extraordinarily powerful but I confess that I resist the power of symbols whenever possible – largely because I think they can obscure a clear view of the moral and political situations we face. I would never want to sacrifice another person to my commitment to a symbol. I worry that that happens far too often.