Paradoxes are fascinating things. Some are especially so on the day of local body elections.

The famous ‘Liar Paradox‘ poses the intriguing claim by a Cretan that ‘All Cretans are always liars’. Of course, if it’s true, it’s false. And, if it’s false, it’s true.

Well, it’s not quite the same, but here’s another conundrum: ‘Every decision determined democratically is a democratic decision’.

[That statement seems, initially, tautologically true. Tautologies, like contradictions (i.e., as in the Liar Paradox) have no sense – according to the early Wittgenstein at any rate.]

What if the decision was to remove democracy? Would that, too, be a democratic decision given it would have been democratically decided?

Sir Gil Simpson – founder of Jade software and various other ‘tech’ companies – presumably thinks so.

But, then again, maybe less democracy is just that – and not an answer for any problem with democracy.

Simpson’s opinion piece makes curious reading from the start – and continues in the same vein.

Sir Gil begins with his own re-write of the past five years or so. The Global Financial Crisis, in Gil’s world, doesn’t even have banks, financial markets or finance houses as bit players in this modern economic drama. No, the problems that vex Sir Gil all stemmed from high-spending governments:

Following the world financial crisis there has been evidence come to light of endemic wide spread economic problems caused by generations of politicians elected by the democratic process.

What the financial crisis uncovered was the incredible debts that politicians had created through social programmes which made them electable, but created an obligation for a future generation which in mild terms is unbearable.

These politicians were “uncovered” because the financial crisis meant they were no longer able to borrow money to fund their programmes.

There’s something wrong with this Cook’s Tour through the financial crisis – and the missing jigsaw piece is, of course, the phenomenal ‘mismanagement’ in the financial sector.

Perhaps it was quite unwise of governments to believe that the private sector would, in the financial world, keep its own house in order.

Perhaps it was imprudent of governments to expect that the economies over which they presided could rely on continuing liquidity provided by the financial sector.

Perhaps it was cavalier of governments to assume that they could rely on the prosperity that, supposedly, the ‘unleashed’ free market in financial derivatives was providing – and cut the cloth of their expenditure accordingly.

But, if all that is true, Sir Gil has got it just about backwards.

When massive financial institutions and banks fall over the problem is one of the operation of financial institutions. It is not a problem with those individuals and public entities – including governments – that went about their legitimate (democratic) business on the assumption that they could rely on those financial institutions to continue to function.

Or does Sir Gil believe that no-one – not an individual, not a company, not a government – should ever borrow money in order to spend or invest it?

Put simply, if there was a political failure – and failure of politicians – then it wasn’t in their spending; it was in their lack of attention to the financial system.

Sir Gil does, however, explain quite clearly how governments were, subsequently, blamed – and by whom:

The lenders of last resort to governments are the IMF and in the case of Europe the European Central Bank (ECB).

These organisations, effectively underwritten by the taxpayers of less- distressed nations, demanded evidence of a responsible government.

They wanted persons to be appointed to key roles so that they felt comfortable that there was a plan to eventually pay the money back.

The term technocrat emerged for people appointed to these various roles from prime ministers to finance ministers.

They are in fact persons who may never have been in politics, but met the requirements of forming a responsible government.

“Responsible government“?

Notice that the responsibility Sir Gil refers to is not responsibility of those governments to their own citizens. No, it is ‘responsibility’ is to those lending the money – the IMF, European Central Bank, etc..

Technically, as Simpson argues, those lenders are “effectively underwritten by the taxpayers of less-distressed nations“.

Less technically – but more realistically – the citizens (aka ‘taxpayers’) of those ‘less-distressed’ countries have about as much say over to whom and under what conditions those institutions lend as the citizens in the ‘more-distressed’ countries have over what is being imposed upon them.

It is not at all clear that a majority of those ordinary citizens in the ‘less-distressed’ countries have supported the imposition of extreme austerity measures upon their fellow ordinary citizens in countries thousands of miles from them as a condition of international financial institutions providing support. Most ordinary people, quite sensibly, believe that the blame should be sheeted home to financial markets, banks and their regulation – not to other ordinary people.

Sir Gil continues:

In reality because of the failure of their politicians other countries insisted that commissioners be appointed to carry out key roles in government.

Citizens of these distressed states had known all along the weaknesses of their political class but had no effective way to address it.

Well, I suppose that’s a twist on the usual refrain that it was the people of these ‘distressed countries’ who were profligately – and ‘immaturely’ in economic terms – voting in politicians who would provide them with ‘cushy’ social systems, public sector pensions, etc.. According to Sir Gil, the ordinary citizens actually wanted rid of the providers of such benefits “but had no effective way to address it“.

But Sir Gil’s rapid revision of recent history is not the main meal on offer in his opinion piece. It’s title suggests the fundamental point: “Voters should be given extra option“.

Simpson’s suggestion is that on local government ballot papers the option of ‘Appoint Commissioners’ should be provided. Despite, or perhaps because of, Cantabrians’ experience of the appointment of Commissioners to Environment Canterbury (ECan) the suggestion is made as a means of getting more effective behaviour on the part of politicians. And, anyway – at least in Sir Gil’s world – appointment of ECan Commissioners was not so much a removal of local democracy as … I’ll let him relate the nuance again:

In Canterbury we have some experience of this by commissioners being appointed to ECan. At the time there was a protest campaign to describe this as the government taking away our democracy.

No popular discontent, then, just a “protest campaign” (organised by malcontents, perhaps) to “describe this” as “taking away our democracy“. The charge of a loss of democracy was simply a matter of some people’s ‘description’.

It would be the Government, under Simpson’s plan, that would appoint these Commissioners. There’s no explanation of how the term of these Commissioners would be set, or how local people would be able to direct central government to ‘un-appoint’ the Commissioners by some specified date. To be fair, the experience of the appointment of Commissioners to ECan doesn’t provide much of a guide for Sir Gil as to how local people might be able to direct Government in this way.

On its own, Sir Gil’s opinion piece would just be an oddity. But it’s certainly true, more broadly, that some people argue that they don’t feel positive about anyone on the ballot papers – locally or nationally – and they’d prefer some kind of ‘no confidence’ option. More revealingly, there’s also the view that it doesn’t matter who you vote for, you get the same result.

What is to be made of this sentiment? For Sir Gil, it’s testimony to the lack of electoral deterrence for politicians’ ineffectiveness and incompetence. This nicely summarises the view of governance as primarily a matter of efficient management – largely of the economic ‘fundamentals’ that are, of course, beyond rational dispute. Efficient management is, then, seen as little more than technical competency – a view of democratic governance that I’ve previously objected to.

He notes that those ‘commissioners’ appointed, in effect, as finance ministers and Prime Ministers in Europe at the behest of international finance institutions have been called ‘technocrats’. That is, people with various technical competencies in running a country.

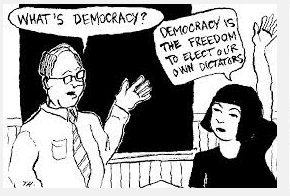

Technocracy, as the name suggests, is a rival to democracy. It is the view that government is best done by experts. As an approach to government, it probably owes something to the ancient greek – Socratic – ideal of philosopher kings.

I should add, however, that few people – like Sir Gil – who advocate technocracy would in reality be supportive of philosophers being appointed as ‘commissioners’. Most likely they would prefer economists, experienced business people or, perhaps, high-level accountants – ‘economist kings’, ‘business kings’ or ‘accountant kings’, so to speak.

It’s an interesting idea but, put this way, I’m not sure it would catch on. Many people remain under the apparent delusion that the current economic crisis has as much by these proposed ‘kings’ as by anyone else – politicians included.

There’s a second interpretation, however, of the ‘no confidence’ sentiment. That interpretation is not so much that the problem is a problem with democracy – corrected by intermittent technocratic intervention – but that it stems from a lack of democracy. A lack, that is, of ‘government by the people’.

Put simply, the sentiment may arise from people feeling that the political system, at present, is not responsive to their wishes. That is, it may be less a concern with ‘competence’ or ‘effectiveness’ – judged by the standards of narrowly specialised ‘experts’ – as with the sense that the political system is captive to interests other than the democratic will of the people in general.

Maybe the extra option on the ballot papers should not be ‘Appoint Commissioners’ but, rather, ‘More Democracy’.

I wonder which would gain more votes?

The outcome of such a ballot might test a few theories. First is the theory, set forth by Sir Gil, to explain the less than 50% turnouts characteristic of local body elections:

Is this the result of voters not being interested or is it a protest about not being happy with the performance of local body politicians?

But it would also test the theory that it is neither a lack of interest nor unhappiness with politicians’ ‘performance’ – instead it results from a lack of belief that our supposed democratic structures are, in fact, democratic.

If the latter passed the test, would Sir Gil and fellow supporters of economic technocracy support making our political systems more deeply democratic?

Or would that be an even greater risk to ‘reasonable’, ‘responsible’ and ‘effective’ government?

Where to start? Sir Gil’s original statement is complete hogwash. Government’s have been forced to borrow to fund basic public services because somewhere along the line (1913), they forgot that they could actually create money themselves and spend it directly into circulation.

No sir, I tell you it is the private banks excessive creation of credit that is the problem. Yes, governments have been populated by representatives who know the system is false but cannot work out anyway of changing it, nor do they wish to face the wrath of corporate media in doing so.

There is a distinct move amongst certain quarters to render local government (and the central government) as incompetent, problematic and therefore a hindrance and unnecessary. This argument can find superficial support because, in the main, local government has been incompetent and failed to constrain costs and bloated bureaucracies. However, we should not confuse poor local government with the need for good local governance. The population has simply been asleep, lulled into a post-materialistic daze, whilst asphyxiating on credit.

The drive for more technocratic government, whilst, like a Big Juicy Fast Food Burger, instantly appealing, should be resisted. In place, more efforts at educating the populace in the concepts of local democracy, citizenship and participation should be introduced. The Swiss model of government is a prime example of what can be achieved.

Sir Gil’s call is most timely. But it is a wake up call and a reminder that the battle for basic human rights is never won and we must always be alert for signs of the slippery slope back towards dictatorship, technocratic or otherwise.

Hi Raf,

Many thanks for the insightful comment.

Yes, there is a real struggle in operation at the moment between what I see as those who would emasculate and sideline the ‘local’ via central and national political interests and power, on the one hand, and those who would affirm more participatory and involving forms of local democracy, on the other.

The latter side appeals to my general sense of how best to meet the future – in terms of sustainability, social cohesiveness and humaneness. Increasing local forms of participation has a beneficial side-effect, too. It ‘up-skills’ more people for future contribution to local government and generally ensures a more informed community. We all, that is, become more like citizens and less like bystanders in our own communities.

And I should add my congratulations to your success in the local elections. There really is a sense of possibility now and, from what I can gather about your background and views, you are definitely a positive aspect of that possibility.

All the very best for the next three years – although I guess what that really means is all the very best to all of us in Christchurch for the next three years.

Regards,

Puddleglum