The grand plan for New Zealand’s own ‘New Jerusalem’ has been revealed.

The excited assurances that, indeed, the Promised Land has been glimpsed have been echoing around the media ( e.g., here, here, here, here, here and here) – fired in perfect sequence, like a 21 gun salute.

(Oh, and another volley here by one of those involved in the 100-day process who, nevertheless, is breathless with amazement at what Bob and Gerry’s well-known madcap inclinations and “clean, green, politically-correct and urban-design-y” sensibilities have conjured up.)

But now that the celebratory cannon have been fired and the vast plumes of smoke are dispersing, the political contours of the new city are becoming clear.

In order to come up for air in this smokey atmosphere it might be worth doing a bit of a catch up. On the catch up list are: (1) the prophets for the New Jerusalem; (2) the ‘naysayers’ (who seem to be proliferating by the day); (3) ‘the plan’ as it has morphed from ‘draft’ to ‘blueprint’, and (4) the most difficult ‘catch up’: future prospects for the plan and consequences for the people of Christchurch if its status ever moves from virtual to real.

Catching up with the ‘Prophets’

On the night when the new Central City Recovery Plan (‘Blueprint’) was announced, Canterbury Chamber of Commerce CEO Peter Townsend (in the second half of this recording and mentioned without attribution in the following link) expressed hopes of Christchurch becoming “the most liveable city in Australasia“.

Less aspirationally, John Key simply thought the plan would “make Christchurch the most liveable city in New Zealand“.

But neither Peter Townsend nor the Prime Minister are as aspirational as they could have been. Before the earthquakes “This pleasant ‘Garden City’“, boasted that it had “been voted one of the most beautiful and liveable cities in the world“.

I guess times have got tough – even for aspirations.

Either that or we don’t actually need a mega sports stadium and Convention Centre to make Christchurch one of the most desirable cities to live in, globally.

But, no – that would be ‘naysaying’ (next section).

Then there was that revealing phrase used by Peter Townsend in the same interview as he urged us all to “drown naysayers in positivity“.

That’s a surprisingly shrill clarion call for an emotional, irrational herd response to anyone who might raise critical objections. Then there’s that notion of ‘positivity’. Isn’t that that stuff hawked on the ‘pop psyc’ shelves in every modern bookstore not worthy of the name?

What is more, if Townsend really means what he said, he might need a pool of positivity bigger than the one envisaged in the Metro Sports Hub in which to do the drowning.

The Central City Development Unit’s own survey of Christchurch residents – miraculously “conducted between 31st July and 1st August 2012” or, with a kinder reading of the phrasing, during the incandescent afterglow of the well-managed son et lumière extravaganza that surrounded the official announcement – found that 13% oppose the plan, 26% are neutral and 5% are ‘Not sure’.

And there will be a lot of blue collars floating in Townsend’s pool:

Blue collar workers were less likely to support the plan (42%) and over a quarter (27%) of those with less than $30,000 (household income) oppose the plan.

Luckily,

those with a larger household income (85% of those over $100,000) and professionals or technicians (67% and 70% respectively) were more likely to support the plan.

But expectations are generally still high here in Christchurch – naysayers aside – and in fact some people appear to be already living in the, as yet, virtual future city centre – like Ezekiel they have been emotionally transported into the very walls of the Celestial City.

In the latest ‘Greater Christchurch Recovery Update‘, for example, Roger Sutton is effervescent with joy at the prospect ahead:

The Recovery Plan is unbelievably exciting.

And;

What thrills me about the Recovery Plan is it’s creating a city for the people. The Frame, Avon River Precinct, an active Square and other green spaces throughout, will make this a place that people want to work in, live in, play in and come to visit.

And;

It’s no secret I am a huge fan of cycling so of course I am thrilled to see a priority network of cycleways and pedestrian walkways. It creates a fantastic opportunity for people to move about the city easily, in an attractive environment.

And;

We will build a giant urban children and young people’s playground in the north end of the East Frame. [How many cubits long, I wonder?] It will be filled with state-of-art play equipment and I hope draw people from afar.

Add to that wonderful new swimming and sporting facilities at the Metro Sports Facility and we will have a city for all people but most importantly one for our children – who are our future.

And;

The Convention Centre, Te Puna Ahurea Cultural Centre and Performing Arts Precinct will make this a fantastic playground for adults too … I hope it all makes people stop and say Wow! – that’s where I want to be, this is the city where I want to live.

It still goes on;

I, like so many others, am staggered by the vision and the boldness of what the CCDU team produced

To cap it off,

I feel extraordinarily proud to be part of this Plan and the recovery of Canterbury.

[By comparison, Gerry Brownlee’s contribution in the same issue comes across as positively restrained and considered.]

But despite such frothy enthusiasm, the best laid plans, as they say …

Catching up with the ‘Naysayers’

But still undrowned and ‘coming up for air’ in this sea of positivity that Townsend tried to summon forth is the likely reality this blueprint presages – once, that is, the digitally induced after-images of the shining city that have been burnt into our collective retinas over the past while have finally faded.

Instances of naysaying are popping up to the surface on a daily basis – the courageous survivors of the positivity tsunami that seemed to sweep all before it in late July. Other oddities have also quietly bubbled up, often unnoticed.

And ‘Coming Up for Air‘ is an apt enough phrase, given that Orwell’s underlying theme for the pre-WWII novel was

“pessimistic, with its view that speculative builders, commercialism and capitalism are killing the best of rural England, ‘everything cemented over’, and there are great new external threats.”

The most vocal naysayers have been the property owners now queuing up to have their concerns plonked centre stage in the media limelight.

First coming to public notice were the owners of the Ng building. It would be hard to find a better example of innovative, creative, determined and transformative post-earthquake development, in commercial terms, than the Ng building and the artistic and allied community it now houses (scroll through the explanation of their ‘space’ and CERA’s plans for it here).

Then there is the co-owner of the now mostly demolished Poplar Lane, Lisle Hood. As he explained,

The Lichfield Lanes project had relied on re-engineering buildings that had “lost their relevance”. Most were disused brick factories and warehouses and had some of the lowest rents in the central city.

“It was about adaptive re-use of buildings and bringing the area back to life. You can’t do that in a new building,” Hood said.

“That sort of [old] building stock has gone out of the city, so we’re going to tend to have a more financially level playing field.

“The city needs those parts of the city that can offer cheaper rent for the start-up incubator-type businesses.”

…

“SOL Square, the Lichfield Lanes area and High St had gone through the largest change of notice renaissance the city had seen for many years. It’s going to be very difficult to recapture that with new buildings.“

In the same link there’s also the ‘glass half full’ view of Laurie Rose who also owns property in the High Street area. But even for a would-be follower of the prophets there are lurking doubts underneath the expressions of faith:

His Project Phoenix group was confident High St could be improved by the plan, but the innovation area and green frame left many unanswered questions.

He was unsure whether the green frame would have a “hard edge” with a dividing green space or a soft edge with some retail activity.

How much High St precinct land would be acquired was the crucial unknown detail.

…

“There’s no reason that I should feel totally negative, but because we don’t have full information it’s difficult to translate it into exactly what the opportunity delivers. There are some questions that require answers.”

Then there’s the owner of The Bicycle Thief cafe/restaurant:

Richard Middleton planned to expand his central-city bar, but the Government’s recovery plan has left it ”on the edge of nothing”.

The Bicycle Thief, on the western side of Latimer Square, was due to reopen next March, but the site falls within the eastern ”frame” of the Christchurch Central Recovery Plan where the Government plans to buy most of the land and keep it open.

By doing so it hopes to drive development to the middle of town, but Middleton cannot see the sense in abandoning the land.

”I love this space. It’s about this area,” he said.

”There needs to be activity and buzz. That’s how our business works.”

Middleton’s renovation plans are on hold as the property, which he leases, will probably be acquired by the Government.

”I couldn’t but help but see my space gone,” he said of the plan.

”We’re on the edge of nothing.’‘

And it’s not just the small entrepreneurs who are getting that vanishing feeling. Some of the central city’s major, premiere car dealerships find themselves within ‘the frame’:

John Hutchinson, of Team Hutchinson Ford, said it was clear that car dealers in the frame would not fit with the plan. …

“We’ve got a fairly big chunk of land here. Not much of it is green, put it that way, but under their plan it certainly looks like it is.”

Hutchinson had yet to hear from or meet earthquake authorities.

“There’s so much speculation,” he said.

“There’s plenty of talk but no-one actually knows what’s going on.”

Relocation would be tricky, he said, because car dealers needed a lot of space and would want to stick together.

“It’s a lengthy task to find out where you want to be,” he said.

Gary Cockram Hyundai principal dealer Dougal Cockram said the plan did not look promising for business.

“There’s a lot of grass. We’re just waiting to hear what they’ve got to say about it, but it seems a bit odd that a business that survived the earthquake and is up and running and working well and [has] got a building in good condition would be one that is ripped apart,” he said.

As Peter Aitken commented,

Many of those inner city dealerships now face dislocation and business interruption of a central/local government engineered kind and not one of a natural disaster. I refer in this instance to the CCRP released this week. As a consequence of the planned precinct for the new reduced city centre, it will mean approximately half of the new vehicle franchise dealerships in Christchurch face relocation.

In simple terms, if a dealership facility is located within the designated southern or eastern frame, CERA has the authority to acquire the land for any of the “anchor” projects. So, at a time when many dealerships were just returning to near-normal trading conditions, and others were looking to rebuild destroyed facilities, they now have to contend with a total about turn. They now face finding a new plot of land and rebuilding from scratch.

As I said, the naysaying is spreading like the pox.

Apparently en masse, the over 800 property owners served with letters of acquisition from CERA are slowing down the purchase process by refusing to complete the property owners survey (you can find it here) that CERA has asked them to complete:

The Christchurch Central Development Unit has sent letters to more than 800 central-city property owners on its intention to acquire their land and asking them to fill out a detailed questionnaire about their property, including the status of any insurance claims.

The unit plans to use that information to help determine the value of the property, but some property owners say the unit is asking for confidential information that their legal advisers do not believe should be made available at this stage.

So far the unit has received only 54 of the 884 questionnaires it sent out.

Denis Harwood, a long-term property investor who owns three sites in the city centre that the Government wants to buy, said he had been advised not to complete the questionnaire and was aware of many others who had been given similar advice.

Harwood said most property owners were unhappy with the acquisition process and felt it was “theft by rezoning”.

The language has been just as heated elsewhere with claims of a ‘Land Grab‘ by a “den of thieves“:

Angry landowners say the Government will profit by selling their sites to someone else, in some cases leaving the original owners severely out of pocket.

The Government has said some of the 840 sites needed for the green frame and civic amenities will be “repackaged” and offered to private interests.

Original owners need not get first refusal, unlike leftover land from Public Works Act purchases for projects such as motorways.

More interestingly, the question of whether such a ‘land grab’ falls under the CERA Act has been raised:

Property lawyer Hamish Grant, of Anthony Harper, said the blueprint had opened a “legal can of worms” and unhappy property owners could try to fight the buy-up.

He said the Government could take land only for earthquake recovery, not “willy-nilly” or to benefit the city or the economy, and could be challenged by judicial review.

“The courts have traditionally come down on governments because they are taking advantage of people’s property rights,” he said.

“But it could be hard to argue. Until someone who is unhappy takes them to task, we just won’t know.”

If correct, Hamish Grant’s comment that land could neither be taken ‘willy-nilly’ nor “to benefit the city or economy” raises asset sale-like questions over how successful the entire project could be, given stubborn resistance.

I’m not a lawyer – though sometimes I wish I were – but even if the CERA Act could be read as supporting land acquisition for ‘economic recovery’ I would have thought there was a few important observations to make on the side of any ‘stubborn resistor’.

First, the problem of the supposedly ‘dying’ central city and the need for its revitalisation pre-dates the earthquakes by many years. So, can CERA also use its extensive powers to solve pre-earthquake problems? Anyone else out there want a hand?

Further, for whom was the supposed withering of the central city a ‘problem’? For the greater ratepayer or citizen abroad in the suburbs of Christchurch? Apparently not, given that they were the ones not going there.

We know, of course, that it was a concern for newly elected councillors Tim Carter and Jamie Gough – the latter appointed to Chair a new committee, which the former also sat upon, to oversee ‘central city revitalisation’ (see page 3 in this link for membership of the committee and its purpose).

But ‘revitalisation’ was already happening, in any case, in places like the Lichfield Lanes, Poplar Lane, Sol Square, etc.., and happening in that usual, quirky, unplanned way that takes time and which recycles run-down buildings that have cheap rents. Perhaps that kind of revitalisation was all part of the ‘problem’ in need of solution?

Then there’s the reason that Christchurch’s economic recovery depends upon a rapidly rebuilt inner city. Well, I guess so. But the ‘facts’ about Christchurch’s economy seem remarkably ‘resilient’ – to use a much-used word. Canterbury people are spending more.

And, according to the ubiquitous and perenially up-beat Peter Townsend,

“Our business survival rate has been just – bizarre,” says Townsend, searching for adequate words. “The normal churn rate in Christchurch for businesses is 11.4 per cent. Last year, it was 11.6 per cent. Almost no different.”

Likewise, he says, rather than mass depopulation, the figures show only 5000 people have left the region – a number about to be reversed with all those arriving for the rebuild.

When you add in the fact that Christchurch is 80 per cent insured for its earthquake damage – compared to 17 per cent for Japan, or 23 per cent for Chile – this means Christchurch’s recovery is assured, says Townsend.

The insurance money may be slow arriving. But Christchurch has not actually taken a backward step in business terms, and most of its rebuild funds are locked in, so the Government has found itself in a surprisingly good position to be adventurous with the new central city design.

Have I just missed something or was that Peter Townsend basically saying that the Central City Recovery Plan now being implemented through unprecedented levels and forms of compulsory land acquisition is not even about economic recovery?

The economy is doing fine – really well, in fact – but CERA’s imposition of the plan will turbo-charge Christchurch? Is that what the CERA legislation was established in order to achieve – the trampling of democratic process to accelerate economic growth beyond Peter Townsend’s wildest dreams?

And, of course, who says this plan will ‘turbo-charge’ Christchurch and Canterbury’s economy? (Apart from, that is, those who will directly benefit from this land rejigging, the ‘anchor projects’ and the shoring up of central city land values west of Manchester Street?).

Are Convention Centres a ‘sure bet’? Are increased rates, potential sell-offs of council assets and increased city borrowing all ‘positives’ for the economy? If ‘yes’, for which parts of the economy and for which ‘players’?

Most recently, valuers are warning the government that the process to buy up land in the CBD is creating chaos:

The valuers say widespread confusion, unrealistic time frames, the lack of dispute resolution process and a background of widely varying sale prices since the earthquakes will create chaos in the blueprint buy-up.

“It’s unheard of; it’s like something from the Third World,” said Wilson Penman, president of the Canterbury branch of the New Zealand Institute of Valuers.

“Some aspects of this are unbelievable; there’s so many things that should have been thought through. These are complex valuations and there’s a lot at stake.”

And Laurie Rose – mentioned above as an owner of property in High Street – seems to be getting more and more worried:

High St property owner Laurie Rose said the valuation rules were “a serious concern” and had been decided without public consultation.

“They will be purchasing at a damaged market value, rather than one that recognises potential.”

Rose said as deadlines loomed, owners would find themselves in a “take it or leave it” situation without bargaining power, and “that’s not a fair market“.

Helpfully, John Key has previously noted that “the central city land [is] ‘not worth a lot in its current state’“.

Finally – will this ‘naysaying’ never end?? – there is also some concern that about one quarter of the remaining listed heritage buildings may be affected by the Central City Recovery Plan, although the Historic Places Trust is living up to its name and trusting that things will turn out ok:

Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (Cera) chief executive Roger Sutton said it was “possible” that the Government would need to acquire heritage buildings to make way for facilities in the blueprint. He said it was too soon to say what would happen to any heritage buildings that were bought.

“This will be determined in the coming months as the Government works through the process of purchasing the land it requires.”

Cera did not have any specific policy for heritage buildings in blueprint areas but would “certainly” consider a building’s heritage value when deciding whether it could be retained, he said. …

The trust had been involved in “high-level discussions” with Cera officials about the central city’s heritage buildings and was confident that most affected sites would be retained.

Sorry about that, but there was quite a bit of ‘naysaying’ to catch up on.

What about the blueprint itself, then?

Catching up with the Blueprint

It seems so long ago now, but at the end of last year the Christchurch City Council released its Final Draft Central City Plan (already ‘re-drafted’ for business early in the year). As the plan noted, it was subject to ‘Ministerial Approval’.

It turned out that the Plan was then ‘uplifted’ out of the arms of the Council and dropped into the awaiting arms of the Central City Development Unit, purpose built to receive it.

It may seem long ago but, as I’ve blogged previously (here and here), only part of the plan was caressed by the CCDU – the first volume, minus the ‘transport’ bit. The second volume with the implementing rules and regulations was ‘put aside for the moment’.

That was an interesting move on Gerry Brownlee’s part and, I suspect, not entirely his own brainwave. There’s something of a debate, as I understand it, in planning circles between the ‘traditional’ view of planning by regulation and the ‘progressive’ view of planning by ‘non-regulatory’ means or by what I would call ‘facts on the ground’ (then having people, almost inevitably, doing what you’d like them to do by responding to those facts and broad, feel-good ‘guidelines’ which lack regulatory authority).

Does the latter sound familiar? The non-regulatory approach is, supposedly, “flexible and can be easier to change (if the complexity of stakeholder and provider relationships is low) and [is] therefore more adaptable to changing needs.”

The approach works best when:

- A good rapport has been developed with a stable local development community;

- There has been a high level of input and buy-in from the development community into the structure plan development process;

- Where concepts expressed in a structure plan are deliberately broad to allow for future flexibility in final design, either because several ‘acceptable design solutions ‘ exist, or adherence to an exact geographic layout is not vital to achieving the desired outcome.

- Where no additional infrastructure is to be provided, or there is certainty about the provision, timing and funding of infrastructure

Now there’s an interesting set of criteria to apply to Christchurch’s situation.

In this complex world of ‘stakeholders’ who are implicitly understood to exist on some sort of level playing field of influence there is, of course, little acknowledgment of how the dynamics of power in a local community governed by a highly centralised authority might operate, and in whose interests.

But I guess I’m just quibbling with such an obviously superior approach to the regulatory one which, as we all know, was always just the beloved ‘red tape’ of sandal-wearing bureaucrats whose sole aim in life was to frustrate developers and property owners – oh, hang on, there’s a few of those around now (see section above). How can that be?

Gerry Brownlee’s siding with the non-regulatory approach was emphatic and the reasons are no secret. When it came to the Draft Plan provided by the Council to him, it was,

Lacking any real power over the developers, the council had to leave it vague about what would actually get built where.

All it could offer was a nit-picky straitjacket of planning regulations – detailed rules on parking, building heights and frontages – in an attempt to force some sort of cohesive outcome.

Realising a more authoritarian approach was needed, the Government decided to go back to the drawing board with the CCDU and a team of outside experts who could draft a plan that was “investment ready“.

There had to be an immediate certainty about how a rebuilt Christchurch was going to look, backed up by a promise that no obstacles would be allowed to stand in its way.

So that’s the non-regulatory approach. By contrast, here are the conditions that favour a ‘regulatory approach’ (from the previous link):

- There is a high level of risk of voluntary agreements being ignored (in which case a regulatory approach can offer legal deterrents and remedies);

- There is instability of landownership and the a [sic] low likelihood of the same developers developing all land and facilities in the structure plan area (often land will be on-sold, possibly to owners or developers with no interest or buy-in to the structure plan);

- There is stability, or a desire for stability in the demand for the type of development envisaged (such that the provisions to be given regulatory effect do not get out of phase with what is desired);

- When there is need to provide certainty in the provision, timing and funding of infrastructure.

If I was doing an ‘eenie-meenie-minie-mo’ between the non-regulatory and regulatory approaches in the case of Christchurch’s recovery, I think I know which option I’d hope my finger rested upon. But then, I’m not Gerry Brownlee.

There’s been one more clarification of the Central City Recovery Plan – one I almost didn’t notice. Here are the 10 design principles that apparently underlie the Plan (By the way, who, exactly, determined that these would be the principles?). The first two refer to ‘Compress’ and ‘Contain’:

1. Design Principle 1. Compress. Compress the size and scale of expected development to generate a critical mass in the core.

2. Design Principle 2. Contain. Contain the core to the south east and north with a fram of green space.

The Council’s Draft Central City Plan certainly spoke about a compact city – in fact its CBD appears even smaller than that proposed in ‘The Core’. Have a look at pages 124-126 where the central city, in its compact form, is detailed. (Notice, too, that the covered market and international quarter have silently dropped off the CCDU plan.) There’s one finger-like extension to that CBD that protrudes down High Street to the South East of the existing CBD in the Four Avenues.

Now, look at the picture of the CCDU Plan that came out on 30 July. It has ‘the frame’ and, therefore, there’s now no South East extension of the CBD. A more stylised picture of it is here, on the first page of the August CERA update.

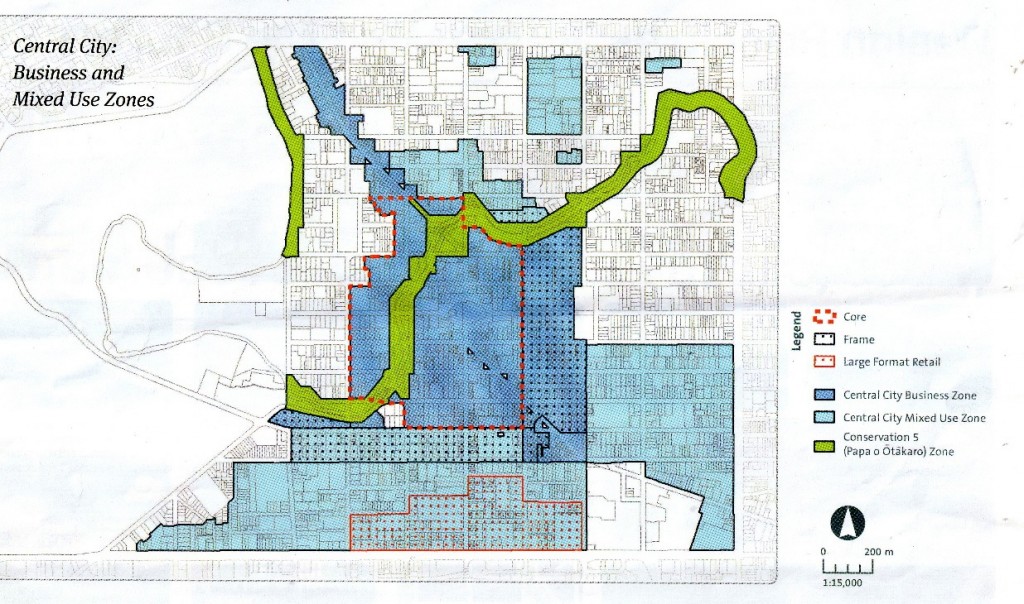

Now, compare those images of the ‘core’ bounded by green (‘the frame’ and the Avon River precinct) with this image (below) of the zones in the CBD resulting from the Blueprint.

Note: I can’t find this publication on-line but it came through our letterbox from CERA and was titled “Christchurch Central Recovery Plan”. The article that incorporated this image was title “The nuts and bolts of rezoning central Christchurch”.

There are three types of zones: Central Business Zone; Mixed Use Zone; Conservation Zone. Notice, first, that only the Avon River is zoned for ‘conservation’ – the Frame is not. In fact, the Frame is zoned ‘Central Business’ in the east and ‘mixed use’ in the south.

Second, as you can see ‘The Core’ is simply a red-dotted line but it is not contiguous with the ‘Central Business Zone’. That zone covers ‘The Core’, parts of ‘The Frame’ and a rather large extension up Victoria Street heading northwest. The accompanying article calls this the ‘Victoria Street gateway’. It’s a very long gateway compared to its opposite, the ‘High Street gateway’ which, in effect is simply that corner of The Frame that has been designated as an ‘innovation precinct’.

Strikingly, the finger-like extension of the central city zone in the original draft plan (mentioned just above) was down Ferry Road (basically continuing High Street, for those unfamiliar with Christchurch’s street layout). In that draft, the CBD zone did not extend up Victoria Street. The extension of the central business zone in the Blueprint, however, pretty much reverses that situation. Why?

Perhaps in the draft it was assumed that the rugby stadium would be somewhere close to where AMI stadium (Lancaster Park) is, thus connecting the CBD with it. But if the resiting of the stadium that occurred with the Blueprint explains the lack of a south east extension we still have the mystery of the appearance of the north-west extension of the central business zone.

Well, that extended ‘gateway’ does point alluringly at Merivale and the lucrative northwest so perhaps that fact alone means that it deserves special exemption from the ‘compact’ design principle (Principle 1) and the principle (Principle 2) to contain the central city to the south, east and north (perhaps north-west is not north?).

The east and south of the old CBD, as Don Miskell explained, “dissolved into a mess of car yards, warehouses and empty lots“. So, ‘messy’ – despite the fact, of course, that many people worked, lived and spent time there.

The down-at-heel east and south of the old CBD were quite unlike Victoria Street with its upmarket retail and commercial premises (many of which have been demolished, but the land is presumably still owned by reasonably well-heeled property owners). They would fit quite nicely, thank you, into the high rental, upmarket plans that the designers of The Core have in mind for the ‘new’ central Christchurch – a place for everyone … with money.

The Blueprint, then, is becoming clearer as the details – often untrumpeted – bob to the surface of the sea of positivity. So, what of the future for the grand plan?

Catching up with the Future

It’s clear that the aim of the Recovery Plan is to transform Christchurch into a neo-liberal city devoted to attracting external – mostly foreign – investment in order to create high-yield rentals for property owners and high-end retailing to service wealthy people, sourced both from within New Zealand (some from Christchurch) and overseas.

It is the image of a city centre re-designed in line with the preferences of those for whom the terms ‘central city’ and ‘downtown’ have always more or less been synonyms for ‘Ballantynes’.

That might help explain why, in the survey mentioned at the start of this post, a full 85% of those Christchurch residents earning over $100,000, 70% of technicians and 67% of professionals supported the plan while 27% of those earning less than $30,000 opposed it.

Will the plan happen as planned? True to its promise, CERA has already issued letters announcing the intention to compulsorily acquire well over 800 properties and – in a way that puts beyond doubt what the main motive for the Blueprint is – there is urgency over that acquisition process. It is a fundamental priority at the very centre of the process – and not because those driving the plan really want to see more parks and a ‘green’ city.

In fact, when told about the results of a survey by The Press about people’s reactions to the plan, Warwick Isaac’s reaction was extremely telling of the mental framework within which those in charge of developing the plan were operating and their primary motives. He was obviously genuinely surprised that mention of ‘green technologies’ was so popular:

Christchurch Central Development Unit boss Warwick Isaacs said he was “thrilled” with the majority of those polled finding the blueprint favourable.

The support for the green frame was vindication of their bold approach.

Isaacs was surprised the use of “green technologies” was so popular, which was “good to know“.

‘Good to know‘? But isn’t the boast that the Blueprint came through big-time on the public’s contributions to the ‘Share an Idea’ process emphasising a ‘green’ city? So, why was the popularity of green technologies news to him?

In that same survey, most people thought that,

the rebuild would take longer than the Government’s schedule, which says most projects should be complete by 2017.

Nearly 70 per cent of respondents thought the rebuild would be completed between 2020 and 2025.

Isaacs points out, in response to that perception, that,

completing the rebuild by 2017 was “optimistic” but having the rebuild continuing up to 2025 would be “too late for the central city to recover . . . It’s our goal to move on [the plan] as quickly as we can . . . it is our commitment to make it happen.”

If you’re wondering what might be in store as the blueprint ‘rolls out’ – on the heroic assumption that it happens as planned and on schedule – it might be worth pondering this extract from a new book by the Guardian’s architecture critic, Rowan Moore.

Moore begins with the story of Dean Gardens, the no expenses spared house software millionaire Larry Dean built with his first wife (of three), Lynda, and largely designed by his 21 year old son Chris. As a monument to the hubris of thinking that a mere building could solve or obliterate the reality of very human and interpersonal problems it excelsl. As Moore explains:

At the heart of this enduring syndrome is the double meaning of the word “home“. It means physical residence, but also the family that inhabit it. It means building, people and relationship. It is easy to imagine that, by fixing the bricks and mortar, one is also fixing the flesh and blood, the more so as buildings seem easier to sort out than people. The results are more tangible, measurable, demonstrable. Because they are expensive and effortful, construction projects offer the appearance of serious attempts to fix something, even if they are irrelevant to the matter in hand.

Advocates for this Blueprint like to claim that not only will it draw investment into central Christchurch but that it will also provide a place and a ‘home’ for residents of Christchurch.

As already quoted, Roger Sutton has visions that the Recovery Plan “will make this a place that people want to work in, live in, play in and come to visit“, there will be playground equipment in ‘the frame’ that will “draw people from afar” and the plan will create “a city for all people but most importantly one for our children.”

Similarly, Mayor Bob Parker in the Spring 2012 ‘Our Christchurch‘ newsletter (not on line yet) states that,

Just as important [as attracting investment] is balancing the sense of community, creating a city which is vibrant and in which today’s and future generations want to call home.

And, in the publication ‘Christchurch Central Recovery Plan‘ that came through my letterbox from CERA, there’s an article titled “A city for the people“. In that, Warwick Isaacs says that, “the central city needs to be a place where people feel comfortable and want to be.”

Someone needs to tell these people that wishing that the ‘bricks and mortar’ will generate the desired social and psychological consequences does not mean that they will. As Moore says, construction projects are “irrelevant to the matter in hand”.

Someone should have also told them that ‘A city for the people’ has to be a city ‘by the people‘ and ‘of the people‘. It is an expression of their individual and collective efforts over time. It expresses what is often termed the ‘vernacular’ culture of an urban centre or neighbourhood.

That vernacular culture matters, both because it ensures that the city can be a place where “people feel comfortable and want to be” and because it is the distinctive quality of a city that makes others want to visit it.

A 2008 article by James Carr and Lisa Servon titled “Vernacular culture and urban economic development: Thinking outside the (big) box” (in the Journal of the American Planning Association) explains the point most clearly.

The article “addresses the increasing homogeneity of urban commercial areas and the loss of local culture associated with this trend.” It found that,

there are at least three types of anchors in neighborhoods with strong vernacular culture: 1) markets; [Note: This was in the Draft Plan but dropped from the Blueprint.] 2) ethnic areas and heritage sites;[Note: An international quarter was in the Draft Plan but dropped from the Blueprint – and best not to talk about heritage.] 3) and arts-and-culture venues and districts. Although the balance between preservation and development will be different in each place, we did cull some widely applicable lessons learned while conducting our fieldwork: a) involve residents; b) find assets in local needs; c) transfer lessons rather than replicating others’ work; d) create opportunities for ownership; e) if it doesn’t exist, invent it; and f) balance culture and commerce.

Compare these findings with what has happened and what is about to happen in Christchurch. Assuming the findings have some validity, what might be predicted for Christchurch and its ‘Blueprint’? How likely is it that Christchurch residents will embrace whatever finally emerges as ‘home’?

By way of an answer, Rowan Moore’s analysis is worth perservering with. In the same link he describes the experience of the planned development of Bijlmermeer, in Holland:

In south-east Amsterdam, an enormous housing development called Bijlmermeer, or the Bijlmer for short, was planned in the late 1960s. It aimed to be the ultimate example of the internationally recognised Dutch genius for planning and an attempt to apply with breathtaking consistency and determination the theories of the time. Homes for 100,000 inhabitants were created in almost identical 10-storey concrete blocks, whose walls and windows were mass-produced in factories, laid out on a hexagonal grid. Parks and lakes filled the spaces between the blocks and roads were built on viaducts, to separate cars from pedestrians and people.

But things soon went wrong. A rail link to Amsterdam never happened. The collective facilities (day care centres, etc.) never happened because “[n]o one had worked out who would pay for the communal facilities and the maintenance of the parks“; construction costs soared so rents went up, meaning the early idealist tenants left.

In 1975, newly independent Surinamese used their new Dutch passports to migrate to Holland and some ended up occupying the flats that remained. Crime increased, flats became overcrowded but the Surinamese also began to transform the planned development into something that supported their culture, festivals and ways of life.

After an aeroplane crashed into some of the blocks leading to their demolition and replacement by lowrise apartments, “the blighted place began to show glimmers of success.”

A thriving weekly market started and a cultural festival, Blij met de Bijlmer (“Happy with the Bijlmer”), was set up. The latter, perhaps burdened by the forced upbeatness of its name, closed after 16 years, but a more successful festival, called Kwakoe, grew from a series of informal soccer matches into an event of music, dance, sport and food that now attracts 400,000 people. Crime started to fall, and if the Bijlmer did not become paradise on earth, it was no longer the sink of despair it was once thought to be.

…

It is hard to imagine anywhere less domestic than the huge, repetitive blocks of the Bijlmer or more alien to the incoming Surinamese. The population of the Bijlmer had to discover, in a few decades, how to inhabit a place through adaptations, actions, successes and mistakes. It is the opposite of the Deans and Soane, who invested everything in the fixed fabric of their homes. The residents of the Bijlmer make their universes around and in spite of the fabric.

In fact, if you live in Christchurch, it might give you a strange feeling that you’re ‘turning Surinamese’. That’s because the challenge for ordinary people is always to make something human and humane out of the debris that is left as the natural consequence of the grand exercise of power.

Yes, as the tortuous example of the Bijlmer makes plain, it is possible to make something your own – make it your home – despite the very fabric of how it was planned, imposed and built without your participation and without you in mind. But it can take a long time:

The Surinamese colonisation of Bijlmermeer suggests that people can make their home anywhere, without or despite the contribution of built form, albeit with considerable struggle.

After ‘catching up’ with how the Recovery Plan for Christchurch’s central city is currently ‘progressing’ the lesson that Christchurch residents should take from it is clear: We’ll have to look to each other – and not to the Blueprint – to make this new Christchurch our home again.

UPDATE: This link adds weight to fears that the Central City, under the Blueprint, will be a place within which only large businesses, corporates and government departments will be able to ‘invest’ and operate:

Government plans to parcel up land it buys in central Christchurch before selling it to private investors could mean small developers and businesses are priced out of the new city centre, experts fear.

They are worried Christchurch’s new central business district will end up devoid of character because only large corporates and government departments will be able to afford a central-city location.

…

“We’re probably going to see a passing of the guard … and potentially a big change to the look and feel of the city,” one developer said.

…

Lincoln University associate professor in property studies John McDonagh agreed that was a worry.

The added cost of building in [Central] Christchurch, coupled with the likelihood that land would be sold in bigger parcels, meant it was unlikely small developers would have much of a role to play in the new CBD, he said.

Small tenants, who had traditionally populated central Christchurch, were also likely to be shut out of the new CBD as rents were likely to be significantly higher than before the quakes.

Have you ever been to Canberra? No? Don’t worry, it’s coming to a town near you … ‘campus feel’ and all. (But, where are all the people???)

I love this! It describes exactly what is happening to us in High Street, we have been working on repairs on our unit in the Duncans Building for 18 months, we have only managed to do 10 weeks work in those 18 months as CERA has made our lives hell, in 18 months no one has told us yet if we are to be demolished. Now I get the letter telling me that they are going to “steal” our land/building from us- maybe/maybe not. (Please supply all the information about your Insurance/rentals/etc.) Do I stop work, do I keep going, what do I do? No one can tell me. (Although CERA advises that I stop work.) We are days away from closing up the building and asking for access to our plant. One of our major problems is that this area supplied cheaper rentals than any other area in the city and 16 tonnes of heavy plant does not shift quickly or easily! (Cheaper rent comes from the re use of older buildings). We are to be an “Innovation Precinct”, what ever that is!) There is no doubt in my mind that “The Frame” was created to push up the prices of the land in the central city at the expense of those in the Frame. It is a David and Goliath situation. Small land owners are being ripped off by the obvious amalgamation of parcels of land. Justice it is not. By the way, the valuers that value our buildings and land are going to value a building that has been locked behind a unnecessary fence for 18 months that has no services. Ethics? I think not.

http://cardmakerschc.wordpress.com/

Hi nicky,

It sounds like you’ve really felt all of this at the very sharp end. To be honest, I’ve heard of plenty of other stories like yours (both in the centre and, of course, in residential areas). It’s bad enough to have all your efforts suddenly made to look like they could be wasted, but it’s another – worse – thing entirely for that to happen in a way that looks to all the world to be an unjust process and an unfair ‘picking off’ of those who don’t have the resources to resist.

Injustice, understandably, makes people angry and bitter and it turns us against each other. We need to do our best to support people who have put in the efforts you obviously have and ‘build’ upon those efforts if we really want to have Christchurch recover both physically and as a community. Instead, those efforts look like they are simply being swept aside.

I really appreciate the honesty of your comment. The more people who know these sorts of details and experiences the better.

Regards,

Puddleglum

First, my own nay-saying:

http://www.ministry.co.nz

and then, the grass roots response which has been a little humbling, given I had no hand at all in its creation:

http://www.facebook.com/events/397320373663779/

http://www.petitiononline.co.nz/petition/oppostion-to-blueprint-exclusion-destruction-of-ministry-nightclub/1565

Hi bruce,

I can’t say I’ve ever been to The Ministry – in my time (late 70s early 80s) I think the only nightclub was a place that I think was called ‘Doodles’ – or something like that – somewhere close to the corner of Colombo and Lichfield (west side of Colombo). But I’ve probably got all that wrong given the strange tricks that time plays on your memory …

There must be some way that all the support for the individual property owners can be ‘joined up’ in some way.

Something more than just businesses, buildings and property is being lost here; it’s not even just our recent past and the central city that was (although that’s more than worth fighting for) – it’s our control over what’s happening to our city.

All the best and thanks for adding your links – I hope it helps a bit having them here!

Regards,

Puddleglum

You are the master narrator!

Many thanks.

I have been sharing your thoughts up on our sites.

I hope you don’t mind.

Kind regards

Nicholas Lynch

http://www.cantabriansunite.co.nz/Nick-Lynch/

Hi Nicholas,

No problem at all with sharing my thoughts elsewhere – and thank you for the compliment.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Could not the owners of a specific area of land incorporate and each hold shares in the company according to the area of land they actually owned. That way they would have more power against……everything.

Another weighty post.

If it’s not too late, you can get down to the Magna Carta Christchurch modeling session and see the real ground up development 🙂

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.10151139200999634.461174.522759633&type=1

Hi Raf,

Yes, another good TED -Ex event. I think it’s pretty clear that there is no shortage of good ideas in Christchurch and willingness to put them forward. My concern is about the process that determines which ideas ‘fly’ and which ones wither on the vine.

We can do it together but, given the legislated role of CERA, I can’t see that that can be anywhere but beyond the margins of that power.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Dear Mr/Mrs. Glum.

Dr. Phil Hayward requested that I forward this on to you. It may be of some interest to you. Regards Nick LYNCH

National Business Review

August 10, 2012

Land Costs Will Strangle Urban Revival

Phil Hayward

Matthew Hooton is not to be blamed for his ideas on CBD land economics in Christchurch; such ideas are widespread (“What Makes Christchurch So Lucky”? Aug 3).

Restricting the area allowed to be developed, by zoning, does indeed drive up rents and force investors into bidding wars with each other. But the assumption that this leads to the most efficient use of land is wrong.

In fact, the cost of land in these conditions, ends up swamping many much more useful incentives to productivity.

Wealth creation involves the utilization of resources to produce something for which there is demand. Healthy and undistorted land markets reflect the actual dollar value of production and income, in land prices; the distribution of the range of land prices depends on agglomeration efficiencies, transport costs, and “location”.

I do not believe that there is proof anywhere in the academic literature, for the supposition that inflating the price of urban land via regulatory rationing and the creation of monopoly rent, results in enforced “increased efficiency”.

In fact, Evans some have found that inflated urban land prices limit the formation of economic agglomerations by “pricing out” enterprises that might otherwise have been included.

New Zealand’s urban economy, including that of Christchurch, was already laboring under the disadvantage of inflated urban land costs due to contemporary planning manias.

It is economic lunacy to strangle the urban economy with inflated costs associated with the crucial “land” factor of production, while regarding the rural economy as some kind of sacred cow to be “protected” from “urban encroachment”.

Christchurch’s economy now has to find a whole lot more income with which to meet the cost of new construction. The market had found its own already-stressed level before the earthquakes. A proportion of tenants only just managed to pay the rent on dilapidated old buildings sitting on grossly price-inflated pieces of land. Now, the urban economy has to adjust to the rental cost of shiny new buildings built to a stricter-than-ever code, on sites that are still grossly over-inflated.

The CBD “plan” would actually have its prospects improved if it included the abolition of all constraints on urban development on the massive quantities of land in Canterbury that are currently off limits, and the adoption of systems of municipal incorporation and infrastructure financing that works so well in the affordable cities of the US. This would bring the urban economic land rent curve in the entire city of Christchurch back to a sensible level and allow for a lot more actual building with the available finance, whether for housing, commercial, or sports stadiums.

I am unconvinced and cynical regarding the “cheering” with which this “Plan” has been greeted. If “the people of Christchurch” really do “want” this, then this is a fine illustration of what some economics writers call “rational ignorance”. It is simply not worth the while of each citizen individually to spend a few hundred hours researching urban economics. Nor would many people understand it anyway. (In fact the NZ Productivity Commission’s recent Report on Housing Affordability noted the predominance of “mom and pop” property investors in NZ in contrast to “institutional” investors, during a speculative mania that has not yet ended. This suggests that even getting involved in property investment is frequently not accompanied by prudent “due diligence”).

The other groups whose “rational” behavior is a factor here are politicians and bureaucrats. Unfortunately, with a few notable exceptions, no-one puts in much effort that really is for the greater good (in contrast to good intentions, ignorance, and “capture”).

Here is the full essay:

Dear Nevil,

I suppose Matthew Hooton is not to be blamed for his ideas on CBD land economics; the fact that such ideas are widespread is all part of the reason western civilisation is now in such a mess.

Restricting the area allowed to be developed, by zoning, does indeed drive up rents and force investors into bidding wars with each other. But the assumption that this leads to the most efficient use of land is wrong.

In fact, the cost of land in these conditions, ends up swamping many much more useful incentives to productivity. “Competition” is sufficient in itself to create all the incentive that is required, for efficient use of land, location, and agglomeration. Forced under-consumption of land by way of inflated prices that are unmoored from the land’s earning potential (much as with the P/E ratio in overheated share markets), actually reduces productivity by varying degrees in all industries.

Alarm bells began to be rung in the UK by various economists in the 1990’s, to the effect that the UK’s urban planning system and its inflated urban land prices were the explanation for the UK’s economic productivity substantially lagging that of comparable nations, the main difference being the responsiveness of urban land supply. “Thatchernomics” would seem to have failed in spite of the many productivity-boosting reforms it imposed in other policy areas. The Thatcher government did attempt a range of reforms of the UK’s land supply regulatory processes, but while some of the names and faces changed, the underlying problem of a massive “planning gain” component in urban land prices remained.

Alan W. Evans (University of Reading) authored a relevant chapter in “The Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, Volume 3: Applied Urban Economics” (1999) edited by Paul Cheshire (of the LSE) and the very distinguished Edwin S. Mills. Evans’ chapter was entitled “The Land Market and Government Intervention”.

In their introduction to the volume, the editors say:

“….Evans (Chapter 42: “The Land Market and Government Intervention”) surveys the still quite small but increasing volume of research on urban land markets and their regulation by governments. Land use zoning is one of the most widespread of all urban policies, yet almost everywhere it has significant effects on relative prices and induces a variety of perverse incentives……”

“……..Yet, Evans provides no account of the impact of regulation on urban uses of land other than housing. These impacts are likely to be at least as significant as they are on housing since we know that land cannot be costlessly substituted out of either production or service activities. If we compare communities in the US and UK that are as comparable as possible except for the constraints their systems of land use regulation place on the supply of land, we observe that the price of retail land is up to 100,000 times higher in the most constrained community (my emphasis). Evans can provide no evidence on the economic impact of such a level of constraint, however, because no research has been done……”

These editors complaint that “no research has been done” has been answered. Evans himself authored two books, published in 2004, that should acquire the status of classics in Urban Economics if they have not already. There is also an important ongoing series of research papers on this subject, from the Spatial Economics Research Centre at the London School of Economics. Their research continues, after definite findings already, of reduced productivity in retail and other analysed sectors of the urban economy.

Besides this, the amount of discretionary income in an urban economy is heavily affected by the cost of land. There was utmost clarity on the subject of land prices, in Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations”; the lack of such clarity, which was clear to many influential voices well into the 20th century, is a sad indictment of just how far our rational faculties have declined in the decadent modern era, and just how far “rent-seeking” interests have succeeded in dominating policy making. Smith pointed out that increases in the price of land, unless the consequence of increased production and increased incomes, represented merely the transfer of wealth rather than its “creation”. There is hardly a more ruinous belief in decadent western civilization today, that wealth is “created” by capital gains in the price of land per se. This is a back-to-front interpretation of classical land economic theory under which the value of land increases because of increased productivity and incomes.

Wealth creation involves the utilization of resources to produce something for which there is demand. Healthy and undistorted land markets reflect the actual dollar value of production and income, in land prices; the distribution of the range of land prices depends on agglomeration efficiencies, transport costs, and “location”. I do not believe that there is proof anywhere in the academic literature, for the supposition that inflating the price of urban land via regulatory rationing and the creation of monopoly rent, results in enforced “increased efficiency” of the use of land in the entire economy, whatever it may be claimed to do in anecdotal puffery. In fact, Evans and others have found that inflated urban land prices limit the formation of economic agglomerations by “pricing out” enterprises that might have been included otherwise. Research suggests that the famous agglomeration of Silicon Valley, for example, became established and achieved its rapid growth at a time when local land was cheap; the use of hitherto-agricultural land for new commercial development was less proscribed in that region than it is today.

Furthermore, the effect on the local economy, of “trickle down” spending by the famous high earners, is very much reduced in contemporary Silicon Valley due to its now very high urban land prices. Research finds far more “spin-off” local jobs for lower income workers, when hi-tech jobs move to Austin, Texas or Raleigh, North Carolina where urban land prices are low. This makes sense because the discretionary spending in the local economy, of all workers, is very much lower when housing costs are high, and vice versa. This effect “compounds” at each “cycle” of the spending of the same dollar. Some people might claim that money paid in housing costs is also recycled back into the local economy; but this is evidently not so. Rentiers may well spend their “unearned” income in yet more speculation and yet more dollars sunk in “dead” costs of land. Mortgage payments boost the incomes of the banking and finance sector, often with the same result, as well as diverting the flow of income into locations such as London and Manhattan, where head offices are based.

“Bust” phases of what is always a more volatile land price cycle under these conditions, destroy the unearned “equity”, while leaving the mortgagee, including the commercial mortgagee, still paying for the increased “cost” of every dollar of actual production with which the land involved is associated, for the term of the mortgage.“Bust” phases of what is always a more volatile land price cycle under these conditions, destroy the unearned “equity”, while leaving the mortgaged party, (whether household or commercial), still paying for the increased “cost” of every dollar of actual production with which the land involved is associated, for the term of the mortgage. We are learning the hard way, worldwide, that land price bubbles are far more ruinous than bubbles in shares and stocks, which tend to have come and gone for decades. The role of land price inflation and deflation in the Great Depression of the 1930’s is tragically little understood. It is worth noting that the limited academic analysis done so far suggests that land prices did not recover to 1920’s levels until the 1950’s, and that property investment substantially under-performed shares over the long term that this painful readjustment was taking place.Hugh Pavletich’s intuitions are correct. In fact he does not make his case anywhere near strongly enough. NZ’s urban economy, including that of ChCh, was already laboring under the disadvantage of inflated urban land costs due to contemporary planning manias. By the way, the urban economy of every nation is far more important that its rural economy, but that is a subject for another essay. Suffice it to say that it is economic lunacy to strangle the urban economy with inflated costs associated with the vital “land” factor of production, while regarding the rural economy as some kind of sacred cow to be “protected” from “urban encroachment” which is derisory in its relative amount anyway.

Christchurch’s economy now has to suddenly find a whole lot more income with which to meet the cost of financing a whole lot of new construction. The market had found its own already-stressed level prior to the earthquakes, whereby some proportion of tenants managed to just pay the rent on dilapidated old buildings sitting on grossly price-inflated pieces of land. Now, apparently the urban economy has to adjust to the rental cost of shiny new buildings built to a stricter-than-ever code, on sites that are to remain, thanks to the “planning” groupthink to which Brownlee and his colleagues have succumbed, grossly over-inflated in price.

This whole “plan” would actually have its prospects improved if it included the abolition of all constraints on urban development on the massive quantities of land in Canterbury that are currently off limits, and the adoption of systems of municipal incorporation and infrastructure financing that works so well in the affordable cities of the USA. This would bring the urban economic land rent curve in the entire city of ChCh back to a sensible level. Sensible site/structure value ratios would allow for a lot more actual building work to be done with the available finance, whether for housing, commercial, or sports stadiums. It is not hard to work out that the owners of land who enjoy the “thousands of times” inflation factor suggested by Cheshire and Mills, represent a powerful rationally incentivized interest group against such reform.

There is in any case, no certainty of “economic benefit” associated with stadiums, performing arts centres, convention centres, and light rail systems; and no objective academic confirmation of any positive benefit/cost for those bearing the cost of subsidy (i.e. ratepayers). Such benefit as does exist, is captured by a small number of property owners, who thus are the beneficiaries of a wealth transfer from ratepayers, most of which is “dead” cost. Furthermore, there is no economic justification for forced “agglomeration” of activities at a central location. Peter Gordon (University of Southern California) and others have been arguing for years that urban economies find their own balance between agglomeration efficiencies and diseconomies associated with congestion, higher land rents, and transport costs. The trend to “decentralization” in urban economies is natural, logical, and powerful. Planning “agglomerations” into existence risks creating an imbalance of diseconomies over efficiencies.

So this writer is unconvinced and cynical regarding the “cheering” with which this “Plan” has allegedly been greeted. If “the people of Christchurch” really do “want” this, then this is a fine illustration of what some economics writers call “rational ignorance”. It is simply not worth the while of each citizen individually to spend a few hundred hours researching urban economics. Nor would many people understand it anyway. (In fact the NZ Productivity Commission’s recent Report on Housing Affordability noted that the predominance of “mom and pop” property investors in NZ in contrast to “institutional” investors, during a speculative mania that has not yet ended, suggests that even getting involved in property investment is frequently not accompanied by prudent “due diligence”). The other groups of people whose “rational” behavior is a factor here, is the politicians and the bureaucrats. Unfortunately, no-one puts in much effort that really is for the greater good (in contrast to good intentions, ignorance, and “capture”), with rare and honourable exceptions like Hugh Pavletich. The media could go in any direction depending on how intelligent their investigative journalists are and who their drinking buddies are.

Yours faithfully

Philip G. Hayward

Lower Hutt

Hi Nick,

Obviously that’s a very long comment – and a bit repetitive – but I thought people reading could sort out for themselves how much of it they wished to read.

One of the ironies for me in all of this is that the political parties most rhetorically committed to ‘markets’ and their efficiencies have simply over-ridden the whole process with a legislative sledgehammer. As a consequence the very small to medium sized (usually local) businesses that have actually got themselves up and running since the earthquakes are amongst those that, potentially, will become ‘collateral damage’.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Not a lawyer either but I did have a quick look at the CERA Act. The key point is the definition of recovery:

“recovery includes restoration and enhancement”

Reword CERA 2001 s17 and it now reads:

“A Restoration and Enhancement Plan for the whole or part of the CBD must be developed […]”

Not sure I would describe the current plan that way. It would be a fascinating legal case.

Hi Donald,

Thanks for that clarification.

‘Enhancement’ – now there’s a ‘contestable’ word if ever there was one. On a broad reading it would allow just about anything (e.g., anything that is bigger than what was there previously, anything that is more expensive …). On a narrower reading it allows pot-shots to be taken at the plan, as proposed (do Convention Centres ‘enhance’ central city areas? Do large sports stadiums enhance central city areas? Does removal of regenerating businesses ‘enhance’ the process of recovery???).

Interesting.

Thanks for your comment – much appreciated.

Regards,

Puddleglum

I haven’t yet been able to give the following study a thorough going over but it seems to be discussing and examining some of the same themes:

http://www.parnell.org.nz/documents/InnerCityConnectednesswebcopyJune2012.pdf

The build environment was not their principle focus according to the Parnell Trust spokesperson – I am assuming that this is because social connections/ opportunities are an adaptive and more readily implemented ‘solution’, or a more organic response to ‘fixed’ parameters. However the build environment is inextricable from this to a large degree, and I think this ties into the MHC’s Blueprint ii, and in a broader sense the idea that we can do better than just make the best of a less than ideal situation. Maybe I am being optimistic, but I am looking forward to reading the rest of the study and thinking about adaptive & proactive sociological initiatives sitting alongside the more gradual (or in some cases not) evolution of the built environment. They are really two halves of the same whole – although at the moment there is somewhat of a temporal disconnect.

Thanks for the link Campbell. I thought this bit from the Executive Summary sounded warning bells for the kinds of apartment housing envisaged in the Plan – situated, as it is, near the mega-stadium (not to mention the general impact of the Convention Centre):

“Large scale events such as the Rugby World Cup were perceived by some as promoting disconnectedness for inner city residents, because they felt imposed upon by the large crowds who influx the inner city en masse and with disregard for local residents’ needs. Respondents also expressed feelings of disconnection where visitors to the inner city coming to experience the night life, made their neighbourhood environments feel unsafe or uncomfortable due to drunken behaviour, noise and the uncleanliness caused. Feelings of disconnection between residents and non-resident daily users of the inner city were also expressed by some respondents.”

Regards,

Puddleglum

Hi Mr/Mrs Puddleglum

I have just realised I used the word “Mortgagee” in the wrong sense one place in my above essay – post supplied to you by Nick Lynch from Cantabrians Unite.

I hope it is not too much trouble Puddleglum to edit the posting online?

The para concerned is:

“Bust” phases of what is always a more volatile land price cycle under these conditions, destroy the unearned “equity”, while leaving the mortgagee……..

etc

The word “mortgagee” there should be “mortgagor”, but as these terms are very poorly understood by the public, I would like to use the term “mortgaged party”.

I would actually like to edit the whole sentence for clarity, to read:

“Bust” phases of what is always a more volatile land price cycle under these conditions, destroy the unearned “equity”, while leaving the mortgaged party, (whether household or commercial), still paying for the increased “cost” of every dollar of actual production with which the land involved is associated, for the term of the mortgage.

Hope it’s not too much hassle for you Puddleglum.

Thanks

Phil Hayward

Hi Phil,

No problem at all. I’ve edited so that the original sentence remains struck through. I hope that is ok. I did it simply for transparency for those who may have read the comment previously.

I can see that you are someone concerned about the precise use of language and, as far as I’m concerned, that is to be encouraged.

Regards,

Puddleglum