[I’ve awoken from my summer slumber and find I have a lot to write. Apologies about the length.]

Well, what was that all about?

As Colin Peacock said when he introduced the Mediawatch item on it, what exactly “put a Catton among the pigeons“?

Can it really just have been about a perceived lack of gratitude?

Was there really outrage over a supposed ‘Taxpayer funded middle finger‘?

Was it even remotely reasonable to call Eleanor Catton a traitor?

The answer to all these questions, so far as I can see, is ‘No’.

So – again – what was it all about?

Maybe this?

That is, did Eleanor Catton just ‘spoil it all’ when she said what she said?

If so, what did she spoil?

When Catton’s comments in an interview in Jaipur (India) were picked up by New Zealand media (e.g., here and here) it was inevitable that New Zealand’s commentariat of head-bobbing pigeons found sufficient cause to fluff their plumage and puff their breasts in agitation.

Especially so given that many of these commentators have in recent decades been raised on a highly processed diet of neoliberal values – and seem to have made themselves well and truly at home in its rudimentary intellectual crate.

And I think that explains a lot.

The critical reaction to Catton’s comments about the government and politicians reduces to two, closely related, reasons that can be summed up in two words.

What it was (mostly) all about, that is, was a head on collision between ‘neoliberalism‘ and ‘intellectualism‘.

I’ll take each of these words in turn.

Whose afraid of ‘neoliberalism’?

The first important point was identified by Morgan Godfrey (amongst others):

Beneath the barely concealed misogyny, the ad hominem attacks and the official disapproval is a very clear message: the role of the writer is not political. The establishment will acknowledge society’s writers and intellectuals, and might even grant them a form of collective importance, yet the writer and intellectual must be denied a private voice.

Or, as studiously reasonable right wing commentator David Farrar put it (leaning on Ecclesiastes), “There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens.”

Or, better yet, in Farrar’s own words:

Good on you for having political beliefs and advocating them [as I said, studiously reasonable]. You did the right thing by appearing at the Green Party campaign launch and advocating a vote for them [I feel a ‘but’ coming on …].

But again your choice of forum to talk politics is perhaps not the best. A campaign launch is an excellent choice to talk politics. A global literary festival seems rather inappropriate for you to rage against the so called neo-liberal agenda in New Zealand.

You – ‘perhaps’ – don’t talk politics at global literary festivals, which is odd given that many literary books have sported highly political themes (the treatment of women, the nature of colonialism, the effects of racism, etc.) and so routinely dissect politically-charged issues.

But such festivals are not, apparently, a place to ‘talk politics’.

Presumably because politics is like a personal hobby – just like it’s a wee bit tedious to buttonhole people at parties to talk about your collection of Royal Family dinner plates you wouldn’t want to spoil a literary festival by discussing your green-tinged collection of political values in an interview. Would you?

Then again, the Jaipur Literature Festival did, very curiously, have the following talks scheduled in its 2015 Program:

War destroys lives and property, and lays waste to whole nations; yet war and the politics of conflict have provided more inspiration to writers than any other subject except love.

“Writing resistance: Of battles and skirmishes.”

Poet, novelist and activist Meena Kandasamy’s debut novel The Gypsy Goddess is based on a massacre of Dalit agricultural workers in Tamil Nadu. Acclaimed writer and poet Ali Cobby Eckerman, in her novel Ruby Moonlight, examines the impact of colonization in mid north-south Australia in the late 1800’s. Celebrated Hindi novelist Mahua Maji’s novels Marang Goda Neelkanth Hua and Me Borishailla focus on the nuances of tribal life and the collateral damage of development.

This session looks at women’s issues in women’s own language. Three writers speak of the gender revolution brewing across Indian cities, universities and villages and indigenous and emerging forms of feminism.

Even as economists debate Gujarat and other models, Rajasthan seeks local strategies for transparency, equity and growth. Jaipur born eminent economist Arvind Panagariya is Vice Chairman of the NITI Aayog. Bibek Debroy is a well known writer, scholar and economist and also a member of the NITI Aayog. In conversation with writer and columnist Malvika Singh, journalist Om Thanvi and journalist Ashok Malik, they discuss the Rajasthan road map.

“A Rediscovery of India: Agendas for Change”

A ‘revolution of rising expectations’ sweeps India as a population of 1.2 billion demands more opportunities and greater choices. Writer, economist and mythologist,

Bibek Debroy, poet and politician Vishvjit Singh and media visionary Subhash Goel discuss the road ahead with writer and journalist John Elliott.

“Toxic Legacy: The Bhopal Gas Tragedy”

Thirty years down the line, the Bhopal Gas Tragedy is still considered the world’s worst industrial disaster, a catastrophe without parallel, where an estimated 10,000 people or more died and possibly 500,000 more suffered the effects of mass poisoning. To mark three decades of an unfulfilled resolution to the tragedy, with no retributive justice or compensatory mechanism, the panel ponders the lessons, learnt and unlearnt, of the night of December 2, 1984.

“Descent into chaos: Pakistan on the brink”

Veteran observer and reporter Ahmed Rashid has unparalleled knowledge about Pakistan and knows intimately its leading players, from presidents to warlords. He is the author of five books on Afghanistan, Pakistan and Central Asia. Here he documents how closely Pakistan’s regime is linked with extremists; how broken promises in Afghanistan have led to a resurgent Taliban fed by drugs money; and the process by which Pakistan is now a breeding ground for terrorism.

I bet Plunket and Farrar are just thankful Catton didn’t put a session together on “New Zealand Neoliberalism and the Challenge to Writing and Culture”!

But, all in all – and as Farrar opines – not really an appropriate place to ‘talk politics’.

Catton, though, is not of course ‘just’ a writer but an initiate into the establishment by virtue of her literary success (and, as Chris Trotter notes, “the near faultless diction of an upper-middle-class girl raised in the comfort and security of a loving academic family“).

So her criticism of the government and use of the ‘n-word’ (neoliberalism) was always going to be particularly galling. As Morgan Godfrey goes on to say:

Catton also offered something critiques of neoliberalism generally lack in New Zealand, Australia and Canada: respectability. Thus her views arrive with far more force than criticisms of neoliberalism that are offered on obscure blogs [ouch!] and in academic journals whose circulations is pathetically small.

Put plainly: For nationalistic and other reasons, Catton – and her success – was put on a pedestal; but then (to paraphrase the lyrics of another worthy piece of art – see video above) ‘she goes and spoils it all by saying something stupid like …’

At the moment, New Zealand, like Australia and Canada, (I [sic] dominated by) these neo-liberal, profit-obsessed, very shallow, very money-hungry politicians who do not care about culture. They care about short-term gains. They would destroy the planet in order to be able to have the life they want. I feel very angry with my government.

Yes, “profit-obsessed, very shallow, very money-hungry” politicians.

If only she’d used the currently fashionable euphemism – ‘aspirational’ – instead.

And just because National MPs crowd out MPs from other parties in the wealth stakes (and here’s a nice satirical take on National MP opulence) that’s no reason to call them “very money-hungry” or “profit-obsessed“.

Doesn’t Catton realise that their hunger pangs are purely for ‘achievement’ and ‘excellence’, not wealth?

No wonder Mr Farrar needed to let out a long, patronising ‘Dear Eleanor’ sigh in response to her ‘outburst’.

More seriously, Farrar also slipped in an ‘off-hand’ observation about Catton’s use of the word ‘neoliberalism’:

Also I would make the point that the moment anyone starts ranting about neo-liberalism, I regard that as a sad victory of sloganeering over substance.

Farrar regards use of the word ‘neoliberalism’ as “sloganeering“. This is confirmed when he mentions a “so called neo-liberal agenda“.

Clearly he is sceptical of the claim that such an ‘agenda’ exists for this government or, perhaps, for anyone in New Zealand.

There’s no explanation as to why he regards use of the word ‘neoliberalism’ as an indication of ‘sloganeering’.

Which leads me to wonder just how much ‘sloganeering’ Farrar (and others?) might see in political discourse. Perhaps it’s everywhere?

Would, for example, use of the term ‘welfare dependency’ – to pluck one of many terms from the ‘neoliberal’ (sorry David) lexicon – be similarly just “a sad victory of sloganeering over substance” for Farrar?

We may never know.

In any event, perhaps I should help Farrar to see more in the word ‘neoliberal’ than mere ‘sloganeering’.

It might be worth giving it a go …

The recent (over)reaction to Eleanor Catton’s comments about being a writer – and, specifically, being a writer in New Zealand – has been like the response of electro-statically charged clouds to a lightning rod. That is, it was instantaneous, explosive and brutally focused. The atmospheric conditions were obviously ideal.

At the heart of the accusations, counter-accusations, rebuttals and plain old abuse is a continuing political conflict that concerns just one thing – those handful of years back in the late 1970s and early 1980s when the planet’s economic and social system was turned on its head. At that point in time the screw of capitalism turned itself tighter.

It’s been called neoliberalism – although that term has a complicated history.

In the 1930s, apparently, the term ‘neoliberalism’ was coined (at a colloquium organised by Walter Lippman) to refer to a ‘Third Way’ between what was seen as a failed, classical liberal laissez-faire form of capitalism and state run economies. In fact, in post-WWII Germany the ‘neoliberals’ managing the economic reconstruction often referred to a ‘social market economy’.

But by the time the term re-emerged in the mid-to-late 1970s it had become used to describe something quite different.

A good place to start to understand the term – especially in its most recent usage – is David Harvey’s seminal work ‘A Brief History of Neoliberalism‘.

It is worth quoting at length from the first couple of pages:

Future historians may well look upon the years 1978–80 as a revolutionary turning-point in the world’s social and economic history. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping took the first momentous steps towards the liberalization of a communist-ruled economy in a country that accounted for a fifth of the world’s population. The path that Deng defined was to transform China in two decades from a closed backwater to an open centre of capitalist dynamism with sustained growth rates unparalleled in human history. On the other side of the Pacific, and in quite different circumstances, a relatively obscure (but now renowned) figure named Paul Volcker took command at the US Federal Reserve in July 1979, and within a few months dramatically changed monetary policy. The Fed thereafter took the lead in the fight against inflation no matter what its consequences (particularly as concerned unemployment). Across the Atlantic, Margaret Thatcher had already been elected Prime Minister of Britain in May 1979, with a mandate to curb trade union power and put an end to the miserable inflationary stagnation that had enveloped the country for the preceding decade. Then, in 1980, Ronald Reagan was elected President of the United States and, armed with geniality and personal charisma, set the US on course to revitalize its economy by supporting Volcker’s moves at the Fed and adding his own particular blend of policies to curb the power of labour, deregulate industry, agriculture, and resource extraction, and liberate the powers of finance both internally and on the world stage. From these several epicentres, revolutionary impulses seemingly spread and reverberated to remake the world around us in a totally different image.

…

Neoliberalism is in the first instance a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade. The role of the state is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practices. The state has to guarantee, for example, the quality and integrity of money. It must also set up those military, defence, police, and legal structures and functions required to secure private property rights and to guarantee, by force if need be, the proper functioning of markets. Furthermore, if markets do not exist (in areas such as land, water, education, health care, social security, or environmental pollution) then they must be created, by state action if necessary. But beyond these tasks the state should not venture. State interventions in markets (once created) must be kept to a bare minimum because, according to the theory, the state cannot possibly possess enough information to second-guess market signals (prices) and because powerful interest groups will inevitably distort and bias state interventions (particularly in democracies) for their own benefit.

As Harvey (2005, pp. 1-2) emphasises, transformations like this “do not occur by accident“.

Rather, “Volcker, Reagan, Thatcher, and Deng Xaioping all took minority arguments that had long been in circulation and made them majoritarian“:

Volcker and Thatcher both plucked from the shadows of relative obscurity a particular doctrine that went under the name of ‘neoliberalism’ and transformed it into the central guiding principle of economic thought and management.

Importantly, “[t]here has everywhere been an emphatic turn towards neoliberalism in political-economic practices and thinking since the 1970s” and

Almost all states, from those newly minted after the collapse of the Soviet Union to old-style social democracies and welfare states such as New Zealand and Sweden, have embraced, sometimes voluntarily and in other instances in response to coercive pressures, some version of neoliberal theory and adjusted at least some policies and practices accordingly.

And, according to Harvey, the penetration of neoliberalism goes beyond the strictly political sphere and reaches well into a society’s cultural and economic institutions:

the advocates of the neoliberal way now occupy positions of considerable influence in education (the universities and many ‘think tanks’), in the media, in corporate boardrooms and financial institutions, in key state institutions (treasury departments, the central banks), and also in those international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization (WTO) that regulate global finance and trade.

In short, neoliberalism has “become hegemonic” and one of the absolutely significant consequences of that for public political debate – especially here in New Zealand – is that,

It has pervasive effects on ways of thought to the point where it has become incorporated into the common-sense way many of us interpret, live in, and understand the world.

For many people, that is, ‘common sense’ itself is now saturated with neoliberal thinking.

No wonder some people just cannot see it – and think references to it are ‘sloganeering’. No wonder successive governments that have implemented (at different speeds) just the kinds of changes Harvey outlines as the distinguishing features of neoliberalism are, nevertheless, called ‘centrist’ and ‘moderate’.

It seems that neoliberal governments with neoliberal agendas are now, for many New Zealanders, just ‘common sense’ governments.

There’s several ways that I think such neoliberal ‘common sense’ has played a role in the controversy over Catton’s comments.

First, one of the transformations that occurred as a result of our own neoliberal revolution was the disbanding of public service radio (the old ZB and ZM networks) and the sell off of radio frequencies to private companies (e.g., the Radio Network/Mediaworks) in order to create a market in radio (a very neoliberal activity).

That means that, thirty years ago, prior to that privatisation and sell off, there were no such things as ‘shock-jocks’ like Sean Plunket but now you can barely turn the dial without hearing one or other of them harangue their listeners with acid-laced opinions.

Why?

Well, if you create a market the new players in the market quite predictably go for market share (actually, in this case it is audience delivery to advertisers). One way to do that in ‘popular’ media such as talkback radio is to be provocative and to sail very close to the wind when it comes to dishing out aggressive rhetoric under the guise of ‘opinion’.

Sean Plunket is actually perfectly capable of ‘holding his tongue’ when the occasion demands it – witness his much more temperate language and manner when dealing with Eleanor Catton’s father, Philip Catton.

And, presumably, he did not indulge himself in this way during his years on National Radio’s Morning Report programme – no doubt partly because his public sector employer would not have supported such behaviour.

In our neoliberal times, however, far from demanding such verbal self-discipline from radio hosts there are rich rewards for those who employ extreme provocation as part of their ‘style’. I have no idea how much Plunket gets paid but my guess is that he did not take a major pay cut when he moved into the private sector.

New Zealand’s neoliberal reforms, that is, provided the platforms for just the kind of reaction we’ve witnessed.

Second, during his initial broadcast on the topic of Eleanor Catton’s comments Sean Plunket repeatedly referenced Catton’s “government funded” job in the public sector (he said “state-funded University” but, actually, her job is with the Manukau Institute of Technology as a part-time tutor) and government/taxpayer support (swiftly detailed by the Taxpayers’ Union).

As Harvey (2005) points out, the push for a minimal state role in the economy is a fundamental principle of neoliberalism. Hand-in-hand with that principle is the call for minimal taxation and general derogation of the state sector – and, typically, of those who work in it.

Earning your living via ‘government funding’ is now seen as almost morally questionable and, certainly, inferior to ‘real work’ in the private sector. This despite the fact that working in the public sector is presumably doing work that the entire country (through its democratic processes) has asked be done. By contrast, in the private sector work is ‘merely’ being done for particular private interests and, at best, a niche of consumers in a market.

Sean Plunket has not been the first person to use this particular neoliberal dog-whistle but he certainly used it very plainly as part of a general attack on others beyond Catton (about 5mins30secs into the audio):

But the number of people – and, you know, I’m thinking about that guy Mike Joy the man who said – a greenie – and goes on about anti-farming and everything; a whole lot of people in government-paid jobs who can do nothing but criticise and be politicised. I think that’s wrong.

[Interestingly, like Catton, Joy has also received a prestigious award – the Charles Fleming Award for Environmental Achievement, 2013 from the Royal Society.]

So, neoliberalism has also provided the ammunition for these attacks via its legitimation of negative attitudes towards the state and the public sector.

Third, the ‘market mentality’ that is part-and-parcel of neoliberalism (and which forms part of its aura of ‘common sense’) prioritises the singular virtue of ‘value in the marketplace’. This ‘value’ amounts to the expressed (or perhaps latent) ‘demand’ for what is being sold (i.e., a good’s’exchange value’).

That is, a thing’s worth is judged primarily by whether or not it is exchanged (i.e., ‘bought’) in a market. That is, the main value question is ‘how much do people want it?’.

When this market mentality enters the political arena – at least in representative democracies – it reduces to a very simple equation: What is right = what is electorally popular.

One of Sean Plunket’s main arguments against Catton’s denunciation of New Zealand politicians and the government was that it amounted to ‘bagging all of us’ (i.e., all New Zealanders). Why? For the simple reason that this government was elected by popular vote.

For Plunket, it seems that the fact that the government was elected undermines Catton’s moral case for criticising it. To criticise a government ‘chosen’ by the people is analogous to the ‘sin’ of criticising a consumer’s preferences in a (legal) marketplace.

The Prime Minister seems to agree with Plunket:

Responding to Catton’s comments, Prime Minister John Key said he was disappointed she felt that way, but not necessarily surprised.

…

“I don’t think that reflects what most New Zealanders perceive of the Government. If it was, they probably wouldn’t have voted for us in such large numbers.

…

“In the end, it’s a free world and people will judge New Zealand on its merits.

“I’m certainly very happy with the reports and the overall progress the Government is making on behalf of all New Zealanders. We had an election and they judged that themselves.”

Neoliberalism emphasises ‘winning’ in competitive markets. For Plunket and Key, a sufficient rebuttal of Catton’s criticisms amounts to saying – in Michael Cullen’s famously childish phrase – “We won, you lost – eat that!”

Though they might add – “so shut up!”

Once again, it is neoliberalism that has provided the assumptions for how we make judgments about what we accept as ‘right’. Principally, we are guided by who ‘won’ (what sells most).

That is, the playing field (platforms), the means of competition (ammunition) and the judgment of success (who is right?/who won?) have all been provided courtesy of neoliberalism.

The second reason for the attacks on Catton relates to the first. and, when in combination, they paint a large and obvious open-season target on Catton’s back that visceral right wingers can spot a mile off.

That reason is that Catton has adopted the one role that many New Zealanders apparently see as a ‘tall poppy’ in need of a good scything – the public intellectual.

Who’s afraid of intellectualism?

Modern economic systems – especially the various stages of capitalism – have not had a great rep over the years in artistic and cultural circles.

Many prominent artists and intellectuals have declaimed, decried and deplored the re-organisation of the social and natural worlds for the economic goals of production, consumption and efficiency.

That this response to our economic system by many artists should surprise (or shock) anyone is itself surprising.

Modern market economies, for example, are often acclaimed as machines composed of mechanisms that supposedly operate only upon an impersonal ‘logic’. That impersonal quality – the supposed blindness of the mechanisms to particular individuals, groups or regions – is often touted as a strength.

Friedrich von Hayek in his book ‘The Road to Serfdom‘ (a pdf is available here) argued, with tremendous psychological and social naivety, that the very impersonal nature of the market was a tremendous social and psychological advantage. This is supposedly because the damage it might impersonally inflict upon individuals would be much more bearable than damage arising from the deliberate planning of those whose ‘hubris’ would lead to a desire to control an economy.

If the crop fails, for example, it is much easier to blame and feel aggrieved by Mao’s collectivisation efforts than to castigate the weather. The weather doesn’t care but we expect (demand) that people do.

It seemed to escape Hayek’s attention, however, that the construction of such an impersonal economic machine would itself always be the deliberate act of particular people (who, in their own way, were therefore planning the economic system if not its yearly outputs) and so the consequences it wrought could, quite reasonably, be sheeted home to such particular persons.

That is, the impersonal market machine inevitably has very identifiable personal (and social) origins and is, in the same sense, personally maintained and enforced by successive politicians. In any psychological and moral calculus the inventor and the ‘maintenance men’ do not get off scot free – no matter how rationally impartial and beyond blame they may wish to see themselves.

Artists, by contrast, have long been the torch-bearers for the more personal, humanly intimate, natural and spiritual aspects of life. ‘Machine logic’ is hardly compatible with that mission.

The cohabitation of modern economies and these seemingly universal artistic sensitivities was therefore never going to be a placid and amicable affair.

When William Blake, for example, memorably evoked England’s ‘dark Satanic Mills’ in Jerusalem (or, in the short poem entitled ‘And did those feet in ancient time‘) it was part of a personal history of criticism of his country and his time clothed, often thinly, in esoteric allegory.

There’s debate over the inspiration for the phrase ‘dark Satanic Mills’ but the conventional interpretation – and surely one that Blake would have been amply aware of when he made his phrase selection – is that in one sense at least it related to the large industrial mills being built in England in Blake’s time.

One such mill – the Albion Flour Mill – was close to Blake’s home. It was burnt down in a suspicious fire. It was also the target of protests from independent millers who were being put out of business by the industrial capacity of the larger mill: The “rotary steam-powered flour mill by Matthew Boulton and James Watt used grinding gears by Rennie to produce 6000 bushels of flour per week“.

As the link above goes on to claim:

Blake’s phrase [‘dark Satanic Mills] resonates with a wider theme in his works, what he envisioned as a physically and spiritually repressive ideology based on a quantifiable reality. Blake saw the cotton mills and collieries of the period as a mechanism for the enslavement of millions, but the concepts underpinning the works had a wider application:

And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion./…

—Jerusalem Chapter 3. William Blake

As one Professor of Theology at Oxford put it, Blake’s works were ‘prophetic’ but in a special sense:

Prophecy for Blake, however, was not a prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best a person can about what he or she sees, fortified by insight and an “honest persuasion” that with personal struggle, things could be improved. A human being observes, is indignant and speaks out: it’s a basic political maxim which is necessary for any age. Blake wanted to stir people from their intellectual slumbers, and the daily grind of their toil, to see that they were captivated in the grip of a culture which kept them thinking in ways which served the interests of the powerful.

Interestingly, “[i]n 1803 Blake was charged at Chichester with high treason for having “uttered seditious and treasonable expressions”, but was acquitted“.

At least today, artists are simply called ‘traitors’ rather than being charged with treason. That’s a significant improvement – in law if not in attitude.

Blake has certainly not been the sole artist in history to see their vocation in this ‘prophetic’ way.

Around the same time, Percy Bysshe Shelley – a prescient voice for the 99% against the 1% – wrote a ‘song’ called ‘Men of England‘. It merged art with politics quite directly and, equally directly, set about ‘bagging’ his country and, according to some interpretations, his countrymen as well (for putting up with their conditions):

Men of England, wherefore ploughFor the lords who lay ye low?Wherefore weave with toil and careThe rich robes your tyrants wear?Wherefore feed and clothe and saveFrom the cradle to the graveThose ungrateful drones who wouldDrain your sweat—nay, drink your blood?Wherefore, Bees of England, forgeMany a weapon, chain, and scourge,That these stingless drones may spoilThe forced produce of your toil?Have ye leisure, comfort, calm,Shelter, food, love’s gentle balm?Or what is it ye buy so dearWith your pain and with your fear?The seed ye sow, another reaps;The wealth ye find, another keeps;The robes ye weave, another wears;The arms ye forge, another bears.Sow seed—but let no tyrant reap:Find wealth—let no imposter heap:Weave robes—let not the idle wear:Forge arms—in your defence to bear.Shrink to your cellars, holes, and cells—In hall ye deck another dwells.Why shake the chains ye wrought? Ye seeThe steel ye tempered glance on ye.With plough and spade and hoe and loomTrace your grave and build your tombAnd weave your winding-sheet—till fairEngland be your Sepulchre.

It is no surprise that one of the many admirers of his work was Karl Marx.

In fact, the entire ‘Romantic’ movement in music, art, literature and poetry in the 19th century was an extended criticism of and reaction to the emergence and growing presence of industrial capitalism and the dehumanising and compassionless values it seemed to embody.

The so-called ‘Arts and Crafts Movement’, for example, was no mere ‘lifestyle’ option as it perhaps would be today. It was a carefully conceived artistic, political and economic movement led by the famous revolutionary socialist, novelist and artist William Morris (best remembered now, perhaps ironically, as a designer of wallpaper but who was also a progenitor of the Bohemian movement and the Bloomsbury set with their social experimentation and rejection of ‘bourgeoise’ ways).

Since its origins, then, capitalism – and the various shades of liberalism that have been its constant bedfellows over the centuries – has provoked a critical artistic (and political) reaction that should be, at the least, pause for thought for those who confidently advocate on its behalf.

Eleanor Catton is clearly a successor of that lineage of artists critical of the forces abroad in their own society. This piece ‘on literature and elitism‘ sits fair and square in that tradition. Here’s a taster of her analysis:

These days, the idea of being a “good reader” or a “good critic” is very much out of fashion — not because we believe that such creatures do not exist, but because we all identify as both. The machine of consumerism is designed to encourage us all to believe that our preferences are significant and self-revealing; that a taste for Coke over Pepsi, or for KFC over McDonald’s, means something about us; that our tastes comprise, in sum, a kind of aggregate expression of our unique selfhood.

We are led to believe that our brand loyalties are the result of a deep, essential affinity between the consumer and product — this soap is “you”; this bank is “yours” — and social networking affords us countless opportunities to publicise and justify these brand loyalties as partial explanations of “who we are”.

The reader who is outraged by being “forced” to look up an unfamiliar word — characterising the writer as a tyrant, a torturer — is a consumer outraged by inconvenience and false advertising. Advertising relies on the fiction that the personal happiness of the consumer is valued above all other things; we are reassured in every way imaginable that we, the customers, are always right.

The idea that a work of literature might require something of its reader in order to be able to provide something to its reader is equivalent, in a consumer context, to the idea that a cut-price mobile phone might require a very expensive charger in order for it to function.

[On reflection, perhaps she should have, instead, taken a leaf out of the All Blacks’ book (not a literal ‘book’, of course) and done something entirely respectable and acceptable (to the right) and quietly and ‘non-politically’ sunk her money into Ryman’s rest homes, or some such private enterprise.

Let your money – not your mouth – do your talking, Eleanor. Let it – not your words -display your values and concerns.

That’s the kind of ‘freedom of speech’ that is beyond reproach in today’s world.]

Yes, ‘then she goes and spoils it all (again!) by saying something stupid …’ this time, can you believe it? – about elitism. The gall of the woman!

It seems to be the fate of writers and intellectuals – down through the centuries they just can’t stop saying stupid things.

And ‘stupid’ would be one of the more polite terms used by critics of such ‘outbursts’ of ‘intellectualism’.

Sean Plunket’s Thesaurus, for example, seems to equate ‘intellectual’ with “a pretentious wanker” or “someone who watches erotica not porn” (From this Mediawatch audio starting at about 17mins30secs).

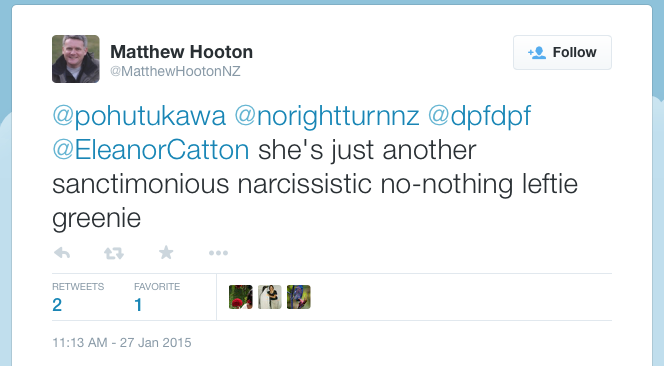

And we’ve already seen what Matthew Hooton thinks of Catton’s credentials for intellectualising – the term “no-nothing” says it all. (Of course, his use of ‘no’ could have been a reaction to Twitter’s character limit, though by my reckoning he still had at least another 20 characters of space left – in fact, enough to slip in another colourful adjective.)

I’d agree that pretension is not good in anyone – least of all someone who has had the privilege of an extended education. I can therefore understand the suspicion felt by many New Zealanders towards those who seem to put on intellectual ‘airs and graces’.

But thinking about things with care, coming up with analyses that show the world in a different light and making connections between different areas of knowledge or human endeavour is actually hard work. And isn’t ‘hard work’ one of those values that New Zealanders are meant to support?

Why should the hard work that some choose to perform with their intellect (rather than their bodies) be derided as a matter or course? And when does the concern with pretension simply become a blanket denial of the worth of thinking and knowing?

To be opposed to ‘intellectualism’ simply because you can think of some pretentious intellectuals would be analogous to being opposed to manufacturing because you can think of some crappy manufactured goods.

Read the passage above from Catton’s article ‘on literature and consumerism’ again (better still, read the whole article).

It takes time, training and intellectual effort to see and then articulate that kind of comparison between the values involved in consumption and the reactions some people have to ‘literary’ writing (that it is all too much ‘hard work’ and so there must be something wrong with the author).

Put bluntly, she’s worked hard (both in writing the actual article and getting to the point in her life where she is capable of writing it).

What Catton is saying may be wrong. It may be being said because she’s defensive about being a ‘literary’ writer. But, nevertheless, it’s an interesting thought and it makes a novel connection between two things we might not normally think had anything in common.

And, who knows, it might even be useful. Not only could it help us understand people’s reactions to ‘literary’ books but it might also have something to say about the decline of investigative journalism (perhaps it’s also ‘too hard’ for potential readers who have drunk deeply from the well of consumerism?) or, even more generally, about any difficulties there might be in instilling values of perseverance in educational settings.

Once again, she may be wrong – but at least we have more ideas, more options, more room to think about things like the kind of world we live in and the kinds of policies that might work (or struggle to work) to make things better.

This is one of the strange aspects of the New Zealand amalgam of neoliberalism and the tradition of scepticism about the worth of ‘intellectuals’.

You’d expect that the intellectual world – often called the ‘free market of ideas’ – would fit like a hand into the glove of neoliberal ideology.

You’d think in a neoliberal-dominated society competition of ideas would not only be welcomed but thoroughly enjoyed by all. There’d be no room for the types of aggressively (or more subtly) dismissive reactions of Sean Plunket, Matthew Hooton or even the Prime Minister.

Yet there are such reactions. Why?

As I said Catton’s piece ‘on elitism and literature’ cited above was the result of hard work and it’s the kind of work that informs, no doubt, her political values and views.

That’s why John Key is entirely mistaken with his claim that,

“She has no particular great insights into politics, she is a fictional writer. I have great respect for her as a fictional writer [sic].”

…

“Obviously it’s done phenomenally well [The Luninaries] and I’m really proud of her, but it would be no different from Richie McCaw or the Mad Butcher or anybody else having a view on politics.

“They’re absolutely entitled to do that, but her views on politics are no more authoritative than anybody else’s.

“I mean, if it’s Corin Dann, and he’s the chief political reporter, then his comments carry more weight because that’s what he does for a job.”

Her claims about our society and our politics do – or should – carry more weight than those of the Mad Butcher or Richie McCaw (once again, that’s not to say she’s right). After all, she has put the time and effort into reading, thinking and crafting her expression of her insights into our society.

With all due respect to the Mad Butcher and Richie McCaw, they’ve devoted their time to other pursuits and – as economists will tell you – there’s always a trade-off, an ‘opportunity cost’ in what you spend your time doing.

Eleanor Catton is unlikely to end up with an empire in meat retailing. She’s even less likely to end up being an All Black captain. But she has ended up having the ability to produce interesting insights into New Zealand society and culture. That is, she’s ended up being an increasingly interesting public intellectual.

And public intellectuals are not people ‘doing a job’ like Corin Dann’s job as a political editor.

What they typically bring to political analysis is not some narrow knowledge about what’s happening in the corridors of political power but, instead, thousands of hours of reading, thinking, discussing and communicating insights about our human world and what it is to live in it.

Public intellectuals see ‘dark Satanic Mills’ not factories. They see ‘stingless drones’ where others just see property owners. They see opportunities that many of us only perceive ‘through a mirror, darkly’. In short, they create new ways to see and understand ourselves.

That means that while we don’t have to believe or be convinced by what Catton has to say it is likely to serve us well to listen carefully – and with an open mind – to what she does say.

So, again, why the antagonism to her comments in our neoliberal society?

Well, in a way Catton has answered that question in her article above. Understanding novel ideas and insights is hard and challenging work and, perhaps ironically, that’s the one type of hard work that brings out the ‘work shy’ side of many New Zealanders.

That intellectual ‘work shyness’, however, is justified by neoliberalism.

Perhaps it’s an ‘unintended consequence’, but neoliberalism is an incubator for this kind of intellectual laziness – and therefore suspicion of intellectual activity – because it elevates individuals’ preferences to a highly privileged status (which justifies running an economy, and therefore society, upon the most efficient basis for their free fulfilment).

Neoliberalism, that is, helps to reinforce anti-intellectualism by arguing ‘What do they know?!’ It comforts the non-intellectually inclined by stating – often explicitly – that what they like and don’t like, what they think (or don’t think) is fine just as it is.

‘You don’t need a know-it-all (or ‘no-nothing’) to tell you what you should think!’ And that, of course, denies the fact that almost everything we think comes from discussion and debate. It does not come from some strange hidden place deep within us. It is not an individual creation.

Or, as Catton says,

The reader who is outraged by being “forced” to look up an unfamiliar word [i.e., a reader who has to ‘work hard’] — characterising the writer as a tyrant, a torturer — is a consumer outraged by inconvenience and false advertising.

Coming to see ourselves more and more as consumers (i.e., adopting the ideology of consumerism in our personal lives) has been, of course, one of the most potent cultural and psychological effects of the neoliberal revolution – it has become part of our ‘common sense’ view of who and what we are. (One way of ‘opening up’ or simply inventing new markets – which is one of the objectives of neoliberal policies – is to encourage the consumer mentality in more and more areas of life.)

To criticise our right to express our ‘consumer preferences’ is therefore, as Catton suggests, a direct attack on our ‘selves’. In fact, you could say that someone who attacked our right to have these preferences was ‘bagging all of us’ – right down to the bedrock of our identity.

This is why criticising our political preferences by ‘hating’ our government feels like being told that someone hates your home.

And this is where neoliberalism and intellectualism part company.

The intellectual world – ‘at the end of the day’ – is larger than the ideology of neoliberalism. That means it provides the space – and the means – to attack neoliberalism.

And, therefore, that space needs to be closed down – it needs to be ‘colonised’ and confiscated by an aggressive neoliberal ‘full court press’.

All ideologies come from intellectual effort (even neoliberalism) which is why all ideologies, ultimately, fear intellectual effort. (You could say that all ideologies have an Oedipus Complex.)

Like a head that pops above a parapet, a lightning rod is raised above our safe little houses so that it extends into the dangers of an electrically-charged atmosphere – and it does so just because it was built for that purpose.

I think that’s what the explosive reaction to Eleanor Catton’s comments has been (mostly) all about.

Or, to put it another way …

‘And then she went and spoilt it all by saying something … not that stupid at all.‘

Kudos to you for using poetry to illustrate your points rather than the ubiquitous and phenomenallylazy and passe GIF files!

As I read the Beatles Eleanor Rigby fluttered through my mind …marvellous discussion. and it is not too long. it deserves the length because Eleanor Catton’s comments are important & hit the target. PS: A spelling error it is MANUKAU .. not Manakau which is a small village outside of Wellington heading towards Levin. I am sure the citizenry would love an institute there. Well Done.

Hi Chris,

I remember ‘doing’ Eleanor Rigby in 3rd Form English.

It struck me then that the ever so personal tragedy of loneliness was something more than simply personal. Father MacKenzie’s ‘job’ and Eleanor Rigby’s social position kept them apart – despite how closely their lives intersected. That haunting question: “Aaah, look at all the lonely people – where do they all come from?” How could there be so much loneliness for such an intensely social creature?

The tragedy was as social as it was personal – ‘writing the words to a sermon that no-one will hear’; his job just wasn’t worth the isolation it created because even what he did was not reaching those it was supposedly for. Despite his social role ‘No-one was saved’ – including Eleanor; and himself.

Thanks very much for the comment – and I’ll correct the spelling 🙂 (I’m not sure if it makes things better or worse but my only defence is that, since 1967, I’ve probably spent no more than four weeks in the North Island :-()

Regards,

Puddleglum

PG,

Happy New Year!

It may be somewhat of a surprise to many, as noted by Harvey, that the so called “free market” is a state sanctioned and supported product. Markets operate because the state, usually through regulation, permits it to do so and sets the rules of engagement. It does that because it does not trust markets to operate honestly, if unfettered by rules (see CDO market and “The Big Short” for further info).

In essence, we have a state supported market system, within which people can express a range of preferences and choices about consumption, and producers can respond accordingly. When the “free” global financial system stared into the void, who pulled it back from the edge? The state. The market would have let it go and immolated a version of itself at the same time, before it rose like a Phoenix. The problem is that would not have suited those who control the levers of the state, namely the funders 🙂

One question I have though, is the impact of technology in this conversation. Was it not technology that drove Ned Ludd and his cohorts to protest? And again technology is changing many structures in society, even the way in which literature and art is delivered. It is changing work systems again, methods of labour and manufacturing processes (the cloud, 3D printing, robotics etc). Will there be another Luddite rebellion or will we accept that arts, culture and spiritual engagement are still all that’s left once production and consumption are complete (ok, violence as well). Can the technological revolution shift the current understanding of arts and culture to a different place? That I believe is the more profound question. The “market” as we know it will likely disappear to be replaced by something more techno-utopian in nature (aspects of the Venus Project perhaps) or something less desirable (a failed Blade Runner type world). Both of these worlds are presented as a question in an interesting book, 2099: A Eutopia, which considers these matters.

As for Eleanor, keep going. We need more debate, not less. After all, ideas are the currency of a free market (society)!! 🙂

Regards

Raf

Hi Raf,

A Happy New Year to you too! It looks like it will be a busy one for you 🙂

Market systems definitely require the continuing operation of an ‘activist state’ to maintain them (and to establish new markets). In fact, I suspect that nation states have been hurriedly cobbled together over the past 150-200 years largely so that markets can be operated (and defended and expanded).

I wonder about the whole technology question as well. Ever since reading Andrew Feenberg’s ‘Questioning Technology’ I’ve been tossing up where my views sit on the matrix he presents in his introduction: The extent to which technology is politically neutral or value-laden and the extent to which the technological sphere is ‘autonomous’ or ‘humanly controlled’.

I know that one of the early modern sciences to develop was mechanics in large part because of the requirement to understand trajectories of cannon-balls (and perfect cannon) and to fortify European cities (i.e., to engineer walls that could hold out against the ballistic technologies being developed). It’s also interesting that much of the technological developments (at least in the domestic sphere) of the last hundred years or so have assumed – and helped advance – processes of individualisation and privatisation of life and experience (the car, household appliances, private dwellings and all the current batch of digital devices – mobile phones, tablets, etc.). If you think about technologies that would have developed in societies in which people were, for example, housed in communal longhouses rather than private dwellings you can see that technology is as much a response, reinforcer and ‘deepener’ of social, cultural and economic relations as it is a harbinger of deep social, cultural and economic change.

Art – and the modern notion of the artist – is part and parcel, of course, of the changes of the last few hundred years. There was that famous comment by Haydn about Beethoven upon hearing Eroica: “From this day forward, everything is changed” – Why? Because Beethoven had dared to put himself at the centre of the work (i.e., his emotion and interpretation) – the first ‘artist as individual expressionist’ of the modern age.

Digitisation and the internet are obviously a challenge for artists today – but how to live a life (and earn income) as an artist (something that a few hundred years ago would have been an odd notion in itself) has been an issue for a while.

As for the Luddites, I remember reading something by Christopher Lasch in which he pointed out that the most ardent revolutionaries are usually not those who perceive themselves as citizens of some future utopia but, in marked contrast, are those who belong to a form of working life that is on the way out because of economic and technological change. I think he used the example of the split in the 19th century labour movement in the U.S. between those who wanted to overthrow the capitalist system and those who wanted to agitate for the best possible pay and conditions from the system. The former were from industries that were organised on a more guild-like system and were on the wain. The latter were in the ‘new’ industries – they won the debate and the ALO (AFL??) was born.

Once again, thanks for the New Year wishes – and for the comment. Really appreciated 🙂

Regards,

Puddleglum

This was a very good read, thank you. It was also my first visit to this site; I shall come back for more!

Mike Moore has been quoted saying “the voters are always right. Even when they are wrong, they are right”. The market motto is “the customers are always right” or “the client is King”, for the obvious reasons stated here. It seems to me that John Key treats voters more like ‘customers’ and views politics as a mutual popularity contest. Of course, Key is not unique in this but he is rather unique in NZ. I guess this why he is sometimes called a “salesman” in a derogatory way, but with an element of truth.

Hi incognito,

Welcome to the site. And thank you for the comment.

I think it’s become part of the ‘common sense’ of politics in New Zealand that electoral popularity is the primary measure of ‘good’ and ‘successful’ politics. That of course starts to divorce politics from outcomes outside of the political process (i.e., effects that don’t dent a politicians popularity).

In fact, in just the same way the effects of market events (e.g., transactions, ‘creative destruction of firms’ , etc.) outside of the market (externalities) are discounted in neoliberalism. In fact, the only way they can be counted is through market effects. That’s part of the impetus to create new markets (e.g., in carbon emissions).

Put bluntly, in an increasingly ‘marketed’ society the only way to even try to solve problems is via ‘success’ in some market or other.

Once again, thanks for taking the time to visit the site (and comment).

Regards,

Puddleglum

Puddleglum, thanks for this thought-provoking essay. The Shelley poem was beautiful and sad.

Previously I didn’t have much interest in Eleanor Catton, but ever since this ridiculous overreaction from our bewildered paparazzi, I feel the need to read some of her stuff.

Kia ora.

Kia ora ropata,

I remember first reading the Shelley poem when I was about 16 (it may have been in a ‘classical’ poetry anthology I had bought because I wanted a copy of Yeats’ ‘Second Coming‘ and Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan‘). I was quite stunned when I first read ‘Men of England’- the realisation that the main defence of the ‘few’ against the ‘many’ was that the many were just after a simple life and so would put up with just about anything before they would rebel against the ‘stingless drones’.

It described the worldview of my family (on my mother’s side especially) to a tee. That strange working class amalgam of deep dissatisfaction and deference; the sense that their lives are, on the one hand, unjustly hard but, on the other, that that is just their place in the world.

Unlike the Prime Minister, I haven’t even read ‘bits’ of The Luminaries 🙂 but, like you, this reaction has made me read her more public writings, listen to her interviews and appreciate her insights.

Thank you very much for taking the time to comment!

Regards,

Puddleglum