“How many people ruin themselves by laying out money on trinkets of frivolous utility? What pleases these lovers of toys is not so much the utility, as the aptness of the machines which are fitted to promote it.”

(Part IV, Chapter 1, ‘Theory of Moral Sentiments‘)

There’s a lot of talk about innovation, inventiveness, new technologies and the like today. There’s precious little discussion, however, of why they appeal.

Asking that question ends up telling us a lot about our modern society.

It might be an article of faith, from an economic perspective, that innovation leads to prosperity via the ‘convenience’, or utility, it provides. What appeals to people, it is assumed, is the extra utility provided by the innovation.

It is also then often argued that one of the precious attributes of our modern world and economy is the vast range of added utility it generates for individuals through the innovative impulse that drives competitive markets. Individuals then get to pick and choose the particular utilities in which they wish to indulge.

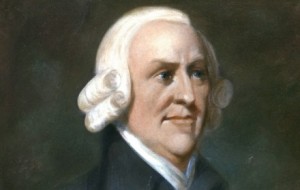

Oddly, Adam Smith – the great 18th century scion and progenitor of free market thinking – thought this kind of justification for the appeal of ‘conveniences’ missed the mark.

For Smith, the additional utility rarely justifies the sacrifices needed to obtain it. It might be a bit of a shock for the economically educated but, for Smith, ‘value-added’ is – at the individual level – generally outweighed by ‘value-lost’.

I’m inclined to agree.

Even more interesting is the much bigger game (than the appeal of technology) Smith is hunting when he first makes this observation.

What Smith’s analysis added to the understanding of the appeal of ‘utility’ (or convenience) is this: It is not the ‘convenience’ in itself that appeals, but the “aptness of the machines that are fitted to promote it“.

What we like about the conveniences our economy provides is not so much the benefit (utility) of the conveniences themselves – as if we ever seriously calculated those benefits – but the simple fact that the ‘stuff’ we make has the well-designed look of providing convenience.

And, according to Smith, we really like that look.

His discussion of this point begins in Part IV of his book ‘The Theory of the Moral Sentiments‘. That Part is straightforwardly titled ‘Of the Effect of Utility upon the Sentiment of Approbation‘. (Approbation is, simply, approval or praise.)

That is, what we desire and admire is that which appears well-designed to deliver the conveniences – it is not the conveniences themselves.

As many people have noted, Apple technology is probably the best current example of the commercial embodiment of this insight, though it is increasingly true of all our modern gadgets.

The mobile phone has become so embedded with a vast array of ‘conveniences’ (‘apps’) that it had to be renamed the ‘smartphone’. It may not be able, literally, to do the dishes but it is more than capable of turning a dishwasher on from a world away.

Smith’s addition to our understanding of the appeal of utility is an intellectually subtle and very neat explanation for the otherwise bewildering and rationally hard to reconcile consumerist economy within which people are immersed in modern societies.

What is even more impressive is that Smith could detect this subtle point in its early manifestations in his own times:

A watch, in the same manner, that falls behind above two minutes in a day, is despised by one curious in watches. He sells it perhaps for a couple of guineas, and purchases another at fifty, which will not lose above a minute in a fortnight. The sole use of watches however, is to tell us what o’clock it is, and to hinder us from breaking any engagement, or suffering any other inconveniency by our ignorance in that particular point. But the person so nice with regard to this machine, will not always be found either more scrupulously punctual than other men, or more anxiously concerned upon any other account, to know precisely what time of day it is. What interests him is not so much the attainment of this piece of knowledge, as the perfection of the machine which serves to attain it.

…

All their [that is, those who spend their money on “trinkets of frivolous utility“] pockets are stuffed with little conveniencies. They contrive new pockets, unknown in the clothes of other people, in order to carry a greater number [cargo pants?]. They walk about loaded with a multitude of baubles, in weight and sometimes in value not inferior to an ordinary Jew’s-box, some of which may sometimes be of some little use, but all of which might at all times be very well spared, and of which the whole utility is certainly not worth the fatigue of bearing the burden.

But Smith’s concerns go far beyond the appeal, at least to some, of gadgets:

Nor is it only with regard to such frivolous objects that our conduct is influenced by this principle; it is often the secret motive of the most serious and important pursuits of both private and public life.

What he has in mind, here, is nothing less than the ‘secret motive’ behind ambition and aspiration to wealth. The parable of the ‘poor man’s son’ that he uses is worth quoting at length:

The poor man’s son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition, when he begins to look around him, admires the condition of the rich. [What some call ‘benign envy‘] He finds the cottage of his father too small for his accommodation, and fancies he should be lodged more at his ease in a palace. He is displeased with being obliged to walk a-foot, or to endure the fatigue of riding on horseback. He sees his superiors carried about in machines, and imagines that in one of these he could travel with less inconveniency. He feels himself naturally indolent, and willing to serve himself with his own hands as little as possible; and judges, that a numerous retinue of servants would save him from a great deal of trouble. He thinks if he had attained all these, he would sit still contentedly, and be quiet, enjoying himself in the thought of the happiness and tranquillity of his situation. He is enchanted with the distant idea of this felicity. It appears in his fancy like the life of some superior rank of beings, and, in order to arrive at it, he devotes himself for ever to the pursuit of wealth and greatness. To obtain the conveniencies which these afford, he submits in the first year, nay in the first month of his application, to more fatigue of body and more uneasiness of mind than he could have suffered through the whole of his life from the want of them. He studies to distinguish himself in some laborious profession. With the most unrelenting industry he labours night and day to acquire talents superior to all his competitors. He endeavours next to bring those talents into public view, and with equal assiduity solicits every opportunity of employment. For this purpose he makes his court to all mankind; he serves those whom he hates, and is obsequious to those whom he despises. Through the whole of his life he pursues the idea of a certain artificial and elegant repose which he may never arrive at, for which he sacrifices a real tranquillity that is at all times in his power, and which, if in the extremity of old age he should at last attain to it, he will find to be in no respect preferable to that humble security and contentment which he had abandoned for it. It is then, in the last dregs of life, his body wasted with toil and diseases, his mind galled and ruffled by the memory of a thousand injuries and disappointments which he imagines he has met with from the injustice of his enemies, or from the perfidy and ingratitude of his friends, that he begins at last to find that wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility, no more adapted for procuring ease of body or tranquillity of mind than the tweezer-cases of the lover of toys; and like them too, more troublesome to the person who carries them about with him than all the advantages they can afford him are commodious.

That’s quite a dismissive account of the aspirational motivation of ‘strivers’ and achievers.

Smith was also not the first thinker to take this view of the desire to acquire the “mere trinkets of frivolous utility” known more commonly as “wealth and greatness“.

Socrates was a very early critic of the pursuit of luxury – a kind of Ancient Greek ‘Tall Poppy Knocker’ (if we allow, for the moment, that being wealthy and famous is what it takes to be entitled to view oneself as a ‘tall poppy’). This essay on ‘Socrates: The Good Life‘ puts Socrates’ view of the ‘Glory of Athens’ and all who ‘strove’ in her in a light almost indistinguishable from Smith’s:

The idea of voluntary simplicity, which became one of the enduring legacies of Socrates’ teachings, had an important political dimension as well. In Book II of Plato’s Republic Socrates leaves no doubt that in his mind a healthy state is a minimal state–a state of economic minimalism. Thus he tells his friend Glaucon, who sees no reason why people should not indulge in materialism and luxuries:

In my opinion the true and healthy constitution of the state is the one which I have described earlier [a society in which only the basic needs of all members are satisfied]. But if you wish to take a look at a society at fever heat, I have no objection. For I suspect that many will not be satisfied with the simpler way of life. They will be for adding sofas, and tables, and other furniture; also dainties and perfumes, and incense, and call girls, and cakes, all these not of one sort, but of all varieties. We must go beyond the necessities of which I was at first speaking, such as houses, and clothes, and shoes. The arts of the decorator and the embroiderer will have to be set in motion, and gold and ivory and all sorts of material must be procured. …. And with that we must enlarge our borders, for the original healthy state is no longer sufficient. (6)

A wealthy state, in Socrates’ estimate, is not a healthy state. The state that exists to secure a luxurious life for its citizens is bound to end up fighting for limited resources, and to engage in expansionist politics and war. Inequality and injustices are sure to follow. The final result (so Socrates implies) would be a state like Athens and her troublesome empire: feared and hated by ever more people, always required to maintain a large military force to preserve order and security, incessantly preoccupied with accumulating ever more wealth, and by no means insured against eventual defeat and disaster. An Athens dedicated to opulence and imperial expansion was, in Socrates’ eyes, a betrayal of the city’s better nature, and a sad waste of her human and cultural potential.

If you intellectually ‘squinted’ a bit when reading Socrates description of “a society at fever heat” you might get the strange feeling that, perhaps, he had travelled forward in time for over a couple of millennia, taken notes from our modern world and then gone back to Athens to warn them about where they – and the world they would inspire – were heading.

Certainly, condemnation of the prioritising of the accumulation of wealth was at the heart of Socrates’ philosophical stance because he saw it as opposed to the wisdom of reflection and understanding. As he famously said in his own defence when on trial for corrupting the youth of Athens:

For I don’t do anything except go around persuading you all, old and young, not to take thought for your social standing or your properties, but first and chiefly to care about the great improvements of the soul. I tell you that virtue is not given by money, but that from virtue comes money and every other good, public and private.

These damning philosophical indictments and analyses of the pursuit of wealth also happen to align very well with what is known about the affect of materialist values on well-being. In short, they don’t make you happy.

Psychologist Tim Kasser, in his book ‘The High Price of Materialism‘, reviews and assembles an impressive body of work that shows – as unequivocally as science can – that the pursuit of fame and fortune (i.e., materialist values) is a losing game when it comes to well-being and happiness. As the blurb in the link summarises:

He [Kasser] shows that people whose values center on the accumulation of wealth or material possessions face a greater risk of unhappiness, including anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and problems with intimacy—regardless of age, income, or culture.

…

He shows that materialistic values actually undermine our well-being, as they perpetuate feelings of insecurity, weaken the ties that bind us, and make us feel less free.

In a little more detail – and when focused on actually being wealthy, rather than simply having materialistic values – the research on the different components of ‘happiness’ (termed ‘Subjective Well-Being’ – SWB) can be summarised in the following way: Wealth can make you satisfied with your life; but, the quality of your relationships are the bedrock of what makes you feel happy.

This recent paper by Diener et al. (2010) summarises the findings from the first survey of the planet and echoes Smith’s – less empirically grounded – conclusions:

Across the globe, the association of log income with subjective well-being was linear but convex with raw income, indicating the declining marginal effects of income on subjective well-being. Income was a moderately strong predictor of life evaluation but a much weaker predictor of positive and negative feelings. Possessing luxury conveniences and satisfaction with standard of living were also strong predictors of life evaluation. Although the meeting of basic and psychological needs mediated the effects of income on life evaluation to some degree, the strongest mediation was provided by standard of living and ownership of conveniences. In contrast, feelings were most associated with the fulfillment of psychological needs: learning, autonomy, using one’s skills, respect, and the ability to count on others in an emergency. Thus, two separate types of prosperity-economic and social psychological-best predict different types of well-being.

The research findings are becoming even more interesting.

Life evaluation (more commonly called ‘life satisfaction’) is a belief (cognition) that depends largely on how one is thinking about life at the time the judgment is made. A recent study provided evidence that economic factors tend to predict life satisfaction only when economic matters (e.g., money) have been ‘primed’ by the context. By contrast, social relationships tend to predict well-being in a more stable manner, irrespective of whether or not thinking about relationships has been experimentally ‘primed’ before the response is given. As the authors conclude:

What makes people happy? Is it simply money, or does happiness stem from looking outwards towards our social networks and communities? The two studies presented suggest that while happiness can have an economic basis, this basis is unstable and dependent on the concepts and values that are activated in the context within which people contemplate their happiness. In comparison, the quality of social relations seems to be a more important basis for individual happiness, and one that is less susceptible to contextual variation.

Put simply, you can make people think that money does – or will – make them happy by constantly cueing ‘money’ and ‘wealth’ in their world; but those self-judgments are fundamentally unstable. By contrast, good social relations are ‘tried and true’ and constant determinants of human happiness.

Completely unsurprising, of course.

Given what is now known – empirically – about the basis of human happiness, Smith’s description of the mind of the ‘poor man’s son’ is a prescient description of the immiserating psychological effects of a person’s pursuit of wealth and fame: “his mind galled and ruffled by the memory of a thousand injuries and disappointments which he imagines he has met with from the injustice of his enemies, or from the perfidy and ingratitude of his friends“.

A ‘galled mind’ and the clear resentment often expressed toward those whom it is believed have not put their noses to the grindstone sufficiently frequently or continuously, seems, to me at least, to be echoed in so many of the harsh and hard phrases which have become so popular in public discourse in New Zealand today.

Throw-away phrases like “harden up“, “suck it up“, “get over it“, “stop whinging/carping/ moaning“, and the like, seem just the kind of public tone that would be expected to arise from a widespread sense of both a deep irritation at others’ perceived laxity and a welling resentment at what one’s own life has required one to endure – both defining characteristics of a ‘galled mind’, as Smith makes clear.

But there’s another twist to Smith’s tale. It turns out that there’s an important difference between the ‘conveniences’ of the wealthy and those of the man whose pockets are full of ‘frivolous trinkets’:

There is no other real difference between them [i.e., between the conveniences of the wealthy and the frivolous trinkets], except that the conveniencies of the one are somewhat more observable than those of the other. The palaces, the gardens, the equipage, the retinue of the great, are objects of which the obvious conveniency strikes every body. They do not require that their masters should point out to us wherein consists their utility. Of our own accord we readily enter into it, and by sympathy enjoy and thereby applaud the satisfaction which they are fitted to afford him. But the curiosity of a tooth-pick, of an ear-picker, of a machine for cutting the nails, or of any other trinket of the same kind, is not so obvious. Their conveniency may perhaps be equally great, but it is not so striking, and we do not so readily enter into the satisfaction of the man who possesses them. They are therefore less reasonable subjects of vanity than the magnificence of wealth and greatness; and in this consists the sole advantage of these last. They more effectually gratify that love of distinction so natural to man.

The utility of the ‘conveniences’ of the wealthy, that is, is better as a visible symbol of status than is that of mere ‘trinkets’. Bluntly, others are more likely to approve (i.e., feel the sentiment of approbation) of obvious wealth (conspicuous consumption).

I’ve always thought that those with wealth protest too much over the supposed ‘tall poppy syndrome’. From Smith’s dissection of the process, it’s now obvious why they might.

What, after all, is the point of having single-mindedly devoted your life to the accumulation of all of these ‘conveniences’ with their ‘obvious’ utility if others will not also praise you (and envy you)? Especially when much ordinary “ease of body” and “tranquility of mind” – and often relationships – may have been sacrificed along the way.

As Smith notes, the conveniences themselves (all the things money can buy – short of power, perhaps) are hardly sufficient recompense for the effort involved in machinating one’s way to such stockpiles of wealth. Without a generous helping of approbation from the social world it might almost seem like it wasn’t worth it at all.

Adam Smith was also the author of ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations‘. That book systematically analysed the nature of modern economies and their system of markets.

It’s therefore not surprising that in ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments‘ Smith concludes his portrayal of the delusional pursuit of wealth in this way:

It’s just as well that nature deceives us in this way. This deception is what starts men working and keeps them at it. It is what first prompted men to cultivate the soil, to build houses, to found cities and commonwealths, and to invent and improve all the sciences and arts that make human life noble and glorious, having entirely changed the whole face of the globe, turning the nature’s primitive forests into agreeable and fertile plains, and making the trackless and barren ocean a new source of food and the great high road of communication to the different nations of the earth. These human labours have required the earth to redouble her natural fertility, and to maintain a greater number of inhabitants.

For Smith, the person who pursues wealth and greatness is like some hapless fool or sap who, deludedly and avariciously, devotes their working hours to accumulating ‘fool’s gold’ (all gold is, in this analysis, ‘fool’s gold’). But, in consequence, all “that make human life noble and glorious” is a happy by-product of this folly.

Notice that such people are, from Smith’s moral point of view, not at all to be admired for their character. Unlike Ayn Rand, for example, Smith finds nothing virtuous about their behaviour. The ‘happy outcome’ is despite their intents, not because of it.

The means are derided, but the ends praised.

And the ends are achieved by that famous “invisible hand”, which is only ever mentioned once, and then in ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments‘, not ‘Wealth of Nations‘.

He leads up to this point by reference to an old saying:

The proud and unfeeling landlord views his extensive fields and—without a thought for the wants of anyone else—imaginatively consumes himself the whole harvest that grows on them; but what of it? The homely and common proverb The eye is larger than the belly is exactly true of this landlord. The capacity of his stomach bears no proportion to the vastness of his desires, and won’t receive any more food than does the stomach of the lowest peasant. He has to distribute the rest among

•those who elegantly prepare the little that he himself makes use of,

•those who manage the palace in which this little is to be consumed, and

•those who provide and service all the baubles and trinkets that have a role in the great man’s way of life.

Thus, all these people get through his luxury and caprice the share of the necessities of life that they would never have received through his humaneness or his justice.

And,

All the rich do is to select from the heap the most precious and agreeable portions. They consume little more than the poor; and in spite of their natural selfishness and greed, and despite the fact that they are guided only by their own convenience, and all they want to get from the labours of their thousands of employees is the gratification of their own empty and insatiable desires, they do share with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to share out life’s necessities in just about the same way that they would have been shared out if the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants. And so without intending it, without knowing it, they advance the interests of the society ·as a whole·, and provide means for the survival of the species.

The ‘distribution’ that arises in this way clearly impresses Smith. And the reason he is impressed by it is just that he sees as entirely delusional the pursuit of wealth and greatness:

When Providence divided the earth among a few lordly masters, it didn’t forget or abandon those who seemed to have been left out in the distribution—these too enjoy their share of all that the earth produces. In terms of the real happiness of human life, they are in no respect inferior to those who seem to be so far above them. In ease of body and peace of mind, all the different ranks of life are nearly on a level; the beggar sitting in the sun beside the highway has the security that kings fight for.

What he’s saying is that, since wealth and greatness are mere frivolities having no real impact on happiness, then they are not of any account in considering the actual ‘distribution’ of goods. The peasant, he claims, has a belly no less full than “the man of greatness“.

Of course, there’s a few problems with this view. Most obviously, when times are hard, it’s likely that it will be the belly of the peasant (and of his or her children) that first ceases to be filled.

And the beggar sitting by the side of the road surely has less security than the wealthy man – which of them, for example, is more likely to fear a ‘bad day’ in income earning terms or to be ‘moved along’, or even imprisoned, when loitering at the side of that road?

But, more central to Smith’s analysis, there’s also a strange inconsistency in his application of his insight that people are drawn towards the pursuit of wealth because of the ‘aptness’ of the conveniences for utility (rather than because of their actual utility).

It almost seems as if Smith is ‘happy’ to let those who actually become wealthy live in ignorance of how deluded and lacking in virtue their behaviour is (since it provides the means for all that is noble and glorious in the world), yet, quite inexplicably and inconsistently, he seems to imply that poorer people must somehow overcome similar ignorance and, like a population of buddhist masters, see how fulfilled their lives actually are in terms of “ease of body” and “peace of mind“.

But perhaps strangest of all is that Smith appears to have missed the most obvious of moral consequences that would arise from the process of pursuing wealth that he describes.

T.S. Eliot’s famous quote from his verse play ‘Murder in the Cathedral‘ was that “The last temptation is the greatest treason: To do the right deed for the wrong reason.”

Smith’s notion of the ‘invisible hand’ is, in effect, falling for this ‘last temptation’ at the level of an entire society. It’s the hubris that, as a society, we will be able to have our cake and eat it too.

We will, that is, be able to unleash the delusional motives of greed and ignorance with the only consequences being the enrichment of us all.

There will be, so Smith seems to imply, no unintended consequences from such a dubious moral gamble. No unfortunate side-effects will arise from our, at least tacit, approval of individuals structuring their lives and behaviours around self-interest.

The ‘moral fibre’ of society will hold firm under all of this reorganisation of our collective lives to free each individual’s delusional aspirations for the good of us all. We will, he seems to think (or certainly does not suggest otherwise), still honour compassion, value justice and extend mercy to others.

Or maybe it won’t be quite like that.

Well, Smith’s experiment has been underway for some time.

If he were to wander through a modern shopping mall and see the poor and rich alike ogling “the aptness of the machines which are fitted to promote” convenience, I wonder how he would judge it to be going?

We’ll never know.

It’s left, then, for us to answer that question.

The quote from Adam Smith which refers to the invisible hand looks very much like the trickle down theory currently being derided by the NZ Initiative/nee Business Roundtable.

Hi Andrew,

Yes, Smith’s analysis has been used to justify the ‘trickle down’ approach. It’s fundamental to Smith’s understanding of economic activity in markets that ‘distribution’ occurs irrespective of the desire to accumulate wealth by the elite. In fact, distribution occurs just because of that desire.

It’s based on the idea that the wealthy – when they spend their wealth – obviously require goods and services to be produced for a price. Everyone therefore benefits from that increased ‘demand’.

Of course, the other side of that desire to accumulate (especially through capitalist endeavour) is the minimisation of costs, primarily labour costs. That’s a ‘dynamic’ that obviously works to reduce the ‘distribution to all’, that Smith highlights, to the barest minimum that can be got away with.

Smith – perhaps because he was a God-fearing presbyterian (or some other form of Christian) – seemed enamoured with absolute levels of goods and services distributed to each member of a population over time through market activity. He didn’t seem to give much thought to the obvious observation that the ability to succeed in any society depends upon access to the means required in that society to succeed. Getting a smaller and smaller share of those means – even if, in absolute terms, the amount of means you have is rising over time – actually traps you at lower and lower levels of attainment in your society. Hardship (or poverty) has to be relative to the means required to succeed in any given society – it clearly isn’t linearly related to an absolute amount of goods and services.

It’s like saying you can compete more successfully in a Formula One race with a bicycle than you could last week when you had no bicycle and had to compete by child’s scooter only against people in ordinary sedan cars.

And, of course, there’s been pretty much a stagnation over the past 30 years in terms of income for many people. In that case, such people are still using a child’s scooter in the Formula One race.

Regards,

Puddleglum

P.S. did the New Zealand initiative actually ‘deride’ trickle-down economics? That surprises me.

Hi Puddlegum

Here is the link to the New Zealand initiative (nee Business Roundtable) piece on the trickle down theory (as defined by them): http://nzinitiative.org.nz/Media/Insights/Our+Latest+Insights.html?uid=472

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for the very interesting link.

I know of Thomas Sowell’s work and have written a couple of blogs about his ‘two visions’ notion (here and here. His views on the non-existence of trickle-down economics are well known (and even part of this Wikipedia article on the term).

It looks to me like the author of that post (Jenesa Jeram) – and the article by Sowell linked to in that post – are in the unfortunate position of themselves creating a ‘straw man’ despite arguing that accusations of ‘trickle-down economics’ represent a straw man.

Sowell says – in an appeal to common sense – that who in their right mind would ‘give’ something to person A in the hope that it gets to B when the obvious thing to do is give it directly to person B and ‘cut out the middle man’? Well, no-one.

What everyone means by criticising ‘trickle down’ economics (philosophy or whatever) is that the world becomes deliberately crafted for those who have the most capital and, surprise, surprise, those with the most capital benefit most. The justification for ‘giving’ them the world crafted in this way is that the benefits of doing so will, despite the accumulations of the wealthy, ‘trickle down’ to the rest of us in just the way that Adam Smith claimed with his simile of the ‘invisible hand'(economists like Sowell call this ‘prosperity’).

That is, a world designed for the rapaciously self-interested will serve the common good as it disperses (‘trickles down’) the benefits of that rapaciousness. That’s the target of the term ‘trickle down’ economics. (To people like Sowell, of course, that’s not ‘trickle down economics’, it’s just ‘economics’. What he dislikes is that a rhetorically powerful description of the consequences of the measures he sees as just ‘sensible economics’ has gained popularity.).

Obviously – and this is the straw man – no-one is saying that the rich are being given ‘money in the bank’ in the hope that that same money will end up in the pockets of the less privileged. What they are being given – which is a far greater gift – is an environment totally suited to their interests and the flourishing of those interests; an environment that, in immediate terms, is hostile to the welfare of most others who are actually just trying to live lives in the midst of this policy hell. Examples of this policy environment are legion – labour laws that massively favour employers, harsh conditions imposed on those on benefits, enactment of youth rates (supposedly to improve the number of ‘jobs’), suppressing (or, in some places, eliminating) minimum wages, the de-regulation of marketing and advertising (to the extent of extensive marketing directed deliberately at children as young as 0-2 years old), increasing indirect taxation (GST, etc.) while reducing direct income tax (and making it less progressive) and, even, in this government’s case in Christchurch, usurping the property rights of many in order to enhance the property values of the relative few.

All of this is ‘given’ to those already with advantage. And the justification is always that it will – in some never-never future – benefit us all: it will ‘trickle down’ to us all … eventually. This is the whole point of a related meme that the wealthy individuals and corporations are the ‘job creators’ and, so, if we want jobs to ‘trickle down’ or forth, all must be arranged for their benefit so that they are free to create these much-desired jobs.

Sowell, in the linked article, says as much while thinking he is debunking the accusation of ‘trickle down economics’. Yet, that is what the criticisms of trickle down economics are aimed at. The straw man version of those criticisms that Sowell and Jeram erect is a disingenuous and evasive piece of clever-dickery that neglects the most obvious fact – the term resonates with ordinary people’s experience of these economic arrangements. They completely discount that experience.

Thanks again for the link. It got me thinking.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Bravo Puddleglum, inspiring stuff. As anyone who’s attempted to negotiate the online jungle of technical discussion on some aspect of consumer digital hardware will have discovered, the marketers know the motivations and foibles of the “poor man’s son” only too well. So much presumption of limitless disposable income, usually for little more than bragging rights.

BTW I’m intrigued by Smith’s use of “Jew’s box”. The nearest that Google yielded was Tthis. Oh dear.

Unlike many of your previous posts, PG, this one seems to have quite a few dilemmas and internal contradictions. It’s irritated me for a couple of days now and while I’d like to say “great post, well said”, I can’t. Nor can I collect and coherently express my concerns. Perhaps it’s my low opinion of Adam Smith clouding my judgement. So, I have to ask – are you sure you’ve said what you meant?

Hi Armchair critic

Interesting comment but hard to know how to respond. I may have to do a close re-read of the post.

Adam Smith is a bit of a curious and in some senses contradictory intellectual when we look back at him. On the one hand, he is famous for his advocacy of a market economy and its ability to distribute goods on the basis of each person pursuing their self-interest.

On the other hand, he has a moral philosophy that sees self-interest as a moral failing. So far as I can reconcile these views he seemed to think that markets, run properly, could at least turn the sow’s ear of self-interest into something approaching a silk purse of general prosperity. I disagree with that, btw.

He was also in favour of ‘industry’ as a virtue but that is different from being motivated to acquire the conveniences of the wealthy in order to gain ‘approbation’. Industry is simply prudent. Greed and acquisitiveness, by contrast, are without virtue.

I don’t know if that helps at all but I’m keen to get to the heart of your concerns.

Regards

Puddleglum

Yeah, sorry ’bout that. I wrote a really long comment, read it, hated it because it was full of its own internal contradictions and pretty incoherent, deleted it and then, in a fit of pique, projected my failings. I’m a bit stuck on the thought that everything that can be said can be said clearly.

So. I read the parable of the poor man’s son as saying that the poor should know their place and not want to rise above their station. That’s not the kind of parable I like, because I disagree with it. Your take on it is a reasonable one too, but it seems a bit hopeful, or generous, to me.

The concept of utility bugs me too, it seems so fundamentally flawed that proposing it without acknowledging its limitations redners discussion of it a waste of time. Not only are we terrible at assessing utility, but in many markets we our evaluation is a binary one. In your iPhone example, the price is set, or fixed, and our decision is “buy” or “don’t buy”, and that’s the same in so many other markets. On a related subject, most of the iPhone owners I know (though not all) find the main benefit of owning it is not the individual apps that their phone has or can have, but that it’s a tool that helps relieve the overwhelming boredom and terrifyingness that is modern (and in my case, corporate) life. Some use their iPhones for work, too.

Hi Armchair Critic,

Thanks for getting back to me – always appreciated.

The ‘parable’ of the poor man’s son, to be fair to Smith, was not meant as a ‘know thy station homily’. Smith’s main target of moral condemnation is almost always the wealthy, avaricious and ruthlessly self-interested. In fact, I’m pretty sure there’s points in the book where he petty much says that you’re more likely to find better character towards the bottom rather than the top of the socio-economic scale. (I quote something along those lines from him in this post, I think).

The parable was also just setting the scene for his argument that the personal advantages or conveniences that might be gained from the life-long pursuit of wealth and copious possessions are unlikely to outweigh the efforts (not just in work effort but also in the psychological and emotional ‘cost’ that goes along with devoting yourself to material acquisition). Therefore, something else must be going on -the ‘pay-off’ is elsewhere.

Where it is, he argued, is in the visibility and ‘noticeability’ of the things wealthy people possess combined with the general tendency for other people to approve of the ‘well-designed’ life they seem to symbolise. (‘Celebrating success’, as our PM likes to call it).

I know what you mean by the problem with the concept of utility. I think the word has a bad press by association with economics’ use of the term. As if somewhere some calculation is made in relation to an individual’s goals or desires. It’s not quite that simple and, hopefully, most economists know that.

Interestingly, I think the point that individuals aren’t good at assessing utility is kind of what Smith is saying. We think we want something because of the benefits in convenience or whatever – and that might be how we justify having it to others and ourselves – but, according to Smith, what really appeals is that the thing looks like it is well-designed for the conveniences it provides. All the apps on an iPhone (and all those deliberately downloaded) aren’t generally acquired because we have any real sense of their ‘utility’ in some sober analysis of what would benefit us overall – we just like the idea of what they are supposedly designed for (‘productivity’, entertainment, social interaction, creativity, self-realisation, etc. etc.). (Of course, all are actually primarily ‘well-designed’ to sell!).

Yes, smartphones definitely are used for reasons other than what the marketers claim they are useful for! Their ‘utility’ is psychological and emotional as much as – often more than – anything more ‘serious’. That’s the point. The marketing is very clever on this; it provides a patina of sensible ‘utility’ (all the specs and the demos of how you can be ‘organised’, on top of life, etc) followed by a finishing flourish of how you’ll also just love it!! Transparent manipulation that provides the ‘rational’ justification for the effort expended (e.g., time spent in a job that you may not thrive in in order to make the money to buy it).

Put simply, what I wanted to show is that we’re caught in a trap that isn’t good for us (hardly original) and that Smith had actually provided one explanation of how we enter the fly bottle. To be honest, I wasn’t really talking about iPhones and their allure. I was trying to highlight how so many people end up living lives of ‘quiet desparation’ while, supposedly, we are freer than we’ve ever been.

Smith thought suffering the delusion of material conveniences (‘utility’) was worth the general prosperity he claimed it led to – I don’t.

Regards

Puddleglum

Pingback: The politics of the empty tomb – Part II | The Political Scientist