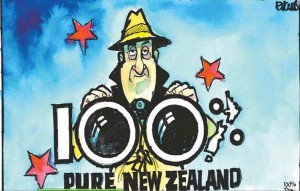

Any potential tourists who may have raised their eyebrows at the prospect of ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ being the agar plate for mass produced botulism (apparently all a sad mistake) will now have their impressions of a pristine country, saved from the horrors of the modern world, further dented with passage of the Government Communications Security Bureau Amendment Bill into law.

At the third reading of the Bill, the Minister in charge of the GCSB – the Prime Minister John Key – made a point of highlighting how vulnerable New Zealand and New Zealanders apparently had become to threats so dire that they could not be described in even the vaguest terms:

“Over the past four and a half years that I have been prime minister, I have been briefed by intelligence agencies on many issues, some that have deeply concerned me.

“If I could disclose some of the risks and threats from which our security services protect us, I think it would cut dead some of the more fanciful claims that I’ve heard lately from those who oppose this bill.”

With those words, John Key clearly signalled to the world that New Zealand is as threatened as any Western country by today’s nebulously worrying world. So much so that we are perhaps the first such country to specify in law the right of a foreign intelligence gathering agency to spy on its own citizens. [To be honest, this is just a guess and I’m only thinking of so-called ‘First World’ countries.]

So much for marketing New Zealand as the place that the modern world’s problems forgot.

Ah, well.

But we have the Prime Minister’s word that ‘100% Pure Surveillance’ is what the new law provides to us – all that is good about being surveilled (for our own good), and nothing that is bad.

Surveillance that is purer than pure.

Through the passage of this law, miraculously, the agency that a matter of only a few months ago was being roundly criticised and ridiculed for its inept lack of awareness of its own powers has presumably been transformed into a precision, finely calibrated instrument for domestic spying – the cyber equivalent of precision bombing and the avoidance of ‘collateral damage’.

Then again, perhaps like the slogan ‘100% Pure New Zealand’, our Prime Minister doesn’t intend us to take that claim too seriously.

After all, just like no-one takes marketing hype literally, perhaps he expects no-one to take his rhetoric over the spying legislation literally?

The analysis of the sections of the Bill (now Act) have received extensive coverage, so I won’t recycle all that useful commentary in any detail here – though I’ll do some of my own amateur exegesis.

The most debated sections have been Sections 8A, 8B, 8C and the new Section 14. There is a useful video of Rodney Harrison QC from the Law Society and Grant Robertson, Labour’s Deputy Leader, discussing some of those issues with Martyn Bradbury on Citizen A.

Harrison also noted in an opinion piece for the New Zealand Herald, the misleading nature of John Key’s claims about ‘wholesale spying’ under the Bill. I’ll return to that point later.

Even the Prime Minister’s assurances of how he will handle the warrant issuing process and his offer of providing a speech during the third reading of the Bill have been very insightfully and systematically dissected by Bryan Gould.

Instead of reviewing all of those criticisms, I’ll stick in this post to three unanswered questions that do not seem to have been much mentioned, although they strike me as being at the heart of a principled opposition to the Bill.

Why are the GCSB’s capabilities suddenly a good reason for sanctioning the bureau to spy on New Zealanders?

A point that has received very little attention in the debate over the GCSB Bill has been the quite incredible rhetorical switch concerning how the capabilities of the agency should be viewed.

One of the original arguments made in favour of the Bill was that the GCSB had capacities which it made sense to use in support of other agencies in their domestic operations (the Defence Force, the SIS, the Police, any other Department or agency of government – well, not the last as it has now been struck out of the legislation, though it was included in previous versions of the Bill). Otherwise, the argument ran, it would be necessary to fund such capacities and capabilities in these other agencies.

Hang on a minute.

The main reason why many countries – including New Zealand up until a week or two ago – at least nominally forbade their foreign intelligence agencies from directly targeting and spying upon their own citizens was just because they are enabled to use wide-ranging methods, technologies and alliances with other foreign intelligence agencies and to use them with minimal democratic oversight.

This is why the NSA is supposedly forbidden, under the oversight of the FISA Court, from collecting communications domestically – although this recent story that has only just come to light because of an Official Information Act request in the U.S. by the ‘Electronic Frontier Foundation’ reveals that the NSA has been doing its best to do just that:

The secretive court that oversees surveillance programs found in 2011 that the National Security Agency illegally collected tens of thousands of emails between Americans in violation of the fourth amendment to the US constitution.

The foreign intelligence surveillance (Fisa) court ruling stemmed from what intelligence officials told reporters on Wednesday was a complex technical problem, not an intentional violation of American civil liberties.

Yet, today, the very reason that once would have been given for not permitting the GCSB to ever have domestic targets is now the reason given for why it should have domestic targets.

The original reasoning for the prohibition is much like that for why the Army, Navy and Air Force are not expected to be employed for crime fighting – their armaments, training and skills have been permitted and honed in order that they can fight foreign enemies in times of war. At present, only the Forces’ non-combatant skills are employed domestically and, then, only in times of a natural disaster. In fact, there has been a recent international training exercise just outside of Christchurch focused on such deployments.

Yet, if the same reasoning were to apply to the Armed Forces as to the GCSB we should now expect a law to be passed permitting the Government to allow the Army to act domestically – using its warcraft capabilities – when either it believes there is a security risk or when other agencies (e.g., the Police) believe that the Army’s warcraft ‘capacities’ will be particularly helpful in apprehending a dangerous criminal or criminals.

Even the same economic arguments over resourcing could be used since money would then not need to be spent on the Armed Offenders Squads and their training. Bazookas, tanks, mines, etc. could all be deployed with only the Prime Minister and a retired judge needed to sign off the action.

Analogously, the GCSB’s communications interception and ‘information infrastructures’ access capacities were only as extensive as they were (pre- the Bill) because it’s always been assumed by Parliament that they would only be used against foreign people and entities who posed a national security risk.

If the GCSB was, from the beginning, permitted to act domestically, it is unlikely that they would now have those capacities that have recently been lauded as just what the doctor ordered for domestic spying and police operations. (And, this ignores the fact that those powers have actually been enhanced in the new legislation, at a time that the Bureau’s scope has been broadened to include domestic ‘information infrastructures’, interception targets and assistance and advice roles.)

It’s also worth remembering that New Zealand has for a long time empowered agencies – the Police and the SIS, no doubt amongst others – to spy domestically. But, once again, part of the justification for that is that their powers, functions and capacities are limited in comparison with agencies charged with foreign spying. That they undertake domestic spying is the very reason why they aren’t allowed to do what the GCSB can do and aren’t equipped with the GCSB’s capacities. Yet, now, that is the reason they are now claimed to need the help of the GCSB.

In effect, what the GCSB legislation has implicitly assumed (and argued for) is that – at the level of communications surveillance – the domestic population is now approaching the level of threat to national security equivalent to foreign people, entities and powers.

That’s the logic behind the legislation. And it’s a stunning logic to embrace.

The immediate question in response to this logic is, of course, to ask whether or not the domestic population now harbours threats to national security of the scale and nature posed from abroad? It depends, of course, on the definition of ‘national security’ or, more importantly, the inclusiveness of the definition of the over-riding objective of the Bureau. The relevant section of the Bill is Section 7:

7 Objective of Bureau

The objective of the Bureau, in performing its functions, is to contribute to—

- “(a) the national security of New Zealand; and

- “(b) the international relations and well-being of New Zealand; and

- “(c) the economic well-being of New Zealand.

Who would have thought that the GCSB has, as part of its objective, contributing to ‘international relations’, the ‘well-being of New Zealand’ (??) and ‘the economic well-being of New Zealand’. On the last point, presumably ‘what’s good for New Zealand is good for any particular company, and vice versa‘?

Despite all these concerns, we do, however, have the Prime Minister’s – rather frustrated sounding – repeated statements that ‘wholesale spying’ on New Zealanders is not what the legislation is about. Those who suggest the legislation leaves this open as a possibility are – as he emphatically stated on the Campbell Live interview – “factually, totally incorrect” [At about 2mins 10 secs].

Which leads to my second question.

In the arcane world of communications surveillance, just what is ‘wholesale spying’?

Well, perhaps ‘wholesale spying’ means something like ‘total intelligence gathering about a population’? But, then, what is ‘intelligence gathering’ and what does the Bill/Act say about it?

A first point – doesn’t the legislation specifically exclude the intelligence gathering function of the GCSB (Section 8B) from targeting New Zealand citizens and residents?

Here’s section 8B:

8B Intelligence gathering and analysis

“(1)This function of the Bureau is—

“(a)to gather and analyse intelligence (including from information infrastructures) in accordance with the Government’s requirements about the capabilities, intentions, and activities of foreign persons and foreign organisations; and

“(b)to gather and analyse intelligence about information infrastructures; and

“(c) to provide any intelligence gathered and any analysis of the intelligence to—

“(i) the Minister; and

“(ii) any person or office holder (whether in New Zealand or overseas) authorised by the Minister to receive the intelligence.

“(2) For the purpose of performing its function under subsection (1)(a) and (b), the Bureau may co-operate with, and provide advice and assistance to, any public authority (whether in New Zealand or overseas) and any other entity authorised by the Minister for the purposes of this subsection.

Interestingly, Section 8B(1)(b) seems to provide licence, as part of this function, to gather intelligence “about information infrastructures” within New Zealand, perhaps as well as those outside New Zealand (though that is presumably harder to do?). And, that (sub)function seems to be worded in such a way that it is independent of the requirement in Section 8B(1)(a) that the intelligence gathering be restricted to “the capabilities, intentions, and activities of foreign persons and foreign organisations“. [It is connected to 8B(1)(a) solely by the word ‘and’.]

Once again, the logic is plain: The function of “intelligence gathering and analysis” (Section 8B) includes gathering and analysing intelligence “about information infrastructures” (i.e., 8B(1)(b)) which can be in New Zealand, and, it can do so as part of its co-operation with, and advice and assistance to, any public authority or other (authorised) entity.

Just as well it’s not ‘wholesale spying’ in New Zealand that is being permitted, then – because that must be really something massive, given what the legislation does empower. And it was this point that Rodney Harrison was trying to make when he wrote:

The GCSB bill abolishes the restraint on GCSB activities to “foreign intelligence”, and instead confers three considerably expanded functions. When Mr Key stated on television that the first of the three things the GCSB would be empowered to do is “foreign intelligence-gathering – nothing to do with New Zealanders”, he was in error. The new 8B function discussed below covers both foreign and domestic intelligence-gathering.

…

Secondly, a new intelligence-gathering and analysis function is to be conferred on the GCSB under 8B. This function is very broadly worded. In particular it permits the gathering of intelligence about “information infrastructures”[i.e., Section 8B(1)(b)]. That is defined widely enough to cover all types of electronic data systems (phones, computers, ISPs and telecommunications networks) and their content.

There is, however, Section 14 of the legislation:

14 Interceptions not to target New Zealand citizens or permanent residents for intelligence-gathering purposes

(1) In performing the Bureau’s function in section 8B, the Director, any employee of the Bureau, and any person acting on behalf of the Bureau must not authorise or do anything for the purpose of intercepting the private communications of a person who is a New Zealand citizen or a permanent resident of New Zealand, unless (and to the extent that) the person comes within the definition of foreign person or foreign organisation in section 4.

So, doesn’t that put a brake on Section 8B(1)(b) that concerns intelligence gathering “about information infrastructures“? Well, no.

First, there has been a revealing change in title to this section. The old Section 14 was “Section 14 Interceptions not to target domestic communications“. “Interceptions not to target domestic communications”, that is, has become ‘Interceptions not to target New Zealand citizens or permanent residents for intelligence-gathering purposes‘. That is, ‘domestic communications’ (communications within New Zealand) can now be intercepted under Section 8B.

Second, the supposed illegality of intercepting “private communications of a person who is a New Zealand citizen or a permanent resident of New Zealand” under Section 14 depends on the definition of “private communications”. How is that defined?

Here it is, from the unaltered Section 4 provision in the 2003 legislation:

private communication—

- (a)means a communication between 2 or more parties made under circumstances that may reasonably be taken to indicate that any party to the communication desires it to be confined to the parties to the communication; but

- (b)does not include a communication occurring in circumstances in which any party ought reasonably to expect that the communication may be intercepted by some other person not having the express or implied consent of any party to do so.

Part b of the interpretation of a ‘private communication’ raises interesting conundrums.

What informs the reasonable expectation “that the communication may be intercepted“? For example, given the revelations about the NSA and GCHQ access to internet traffic (including, now, encrypted traffic), perhaps it is entirely unreasonable for a New Zealander to believe that any of their internet communications will not be intercepted by “some other person not having the express or implied consent of any party to do so” (e.g., the NSA, the GCHQ).

Third, section 14 refers to ‘interceptions’. Those, presumably, are the actions covered by ‘Interception Warrants’, as permitted under Section 15A(1)(a) of the 2013 Act:

15A Authorisation to intercept communications or access information infrastructures

-

“(1)For the purpose of performing the Bureau’s functions under section 8A or 8B, the Director may apply in writing to the Minister for the issue of—

-

“(a)an interception warrant authorising the use of interception devices to intercept communications not otherwise lawfully obtainable by the Bureau of the following kinds:

-

“(i)communications made or received by 1 or more persons or classes of persons specified in the authorisation or made or received in 1 or more places or classes of places specified in the authorisation:

-

“(ii)communications that are sent from, or are being sent to, an overseas country:

But does Section 14 apply to the other kind of authorisation; the ‘access authorisation’? If it doesn’t, then that presumably leaves a hole in the protections the section supposedly provides. Here’s Section 15A(1)(b):

(b) an access authorisation authorising the accessing of 1 or more specified information infrastructures or classes of information infrastructures that the Bureau cannot otherwise lawfully access.

One- or more – “classes of information infrastructures” presumably means something like ‘telecommunications providers’. Would that be close enough to ‘wholesale spying’ for the Prime Minister? Say, under Section 8A that permits the ‘cybersecurity’ function of the GCSB?

I guess it depends on what the GCSB actually does when it ‘accesses’ an ‘information infrastructure’?

Helpfully, the Prime Minister provided the public with a metaphor to demonstrate how no “mass surveillance” was occurring under sections of the Act such as 8A. In the video leading up to John Key’s rapid exit from a recent press conference, he described the way in which the cybersecurity function of the GCSB (covered in Section 8A) did not amount to “wholesale surveillance”.

It is, apparently, just like pouring water through a filter [about 25secs into video]. Only for the ‘nano-second’ that it is passing through the filter could it technically – by those picky lawyers – be called metadata being stored … or something.

In saying this, it was almost as if he was channelling Barack Obama when, during a press conference, he too felt the need to clarify what his foreign intelligence communications agency (the NSA) was doing with ‘metadata’:

Now, let — let me take the two issues separately. When it comes to telephone calls, nobody is listening to your telephone calls. That’s not what this program’s about. As was indicated, what the intelligence community is doing is looking at phone numbers and durations of calls. They are not looking at people’s names, and they’re not looking at content. But by sifting through this so-called metadata, they may identify potential leads with respect to folks who might engage in terrorism. If these folks — if the intelligence community then actually wants to listen to a phone call, they’ve got to go back to a federal judge, just like they would in a criminal investigation. So I want to be very clear. Some of the hype that we’ve been hearing over the last day or so — nobody’s listening to the content of people’s phone calls.

So, this metadata ‘filtering’ – or ‘sifting’ as Obama prefers to call it – is just a case of filtering the ‘water’. And, the ‘water’ is the traffic through an organisation or ‘information infrastructure’ (a telecom operator, an ISP, a mobile network or, presumably, NZ Post – is the law restricted to electronic communcations?), or at least part of it.

The cybersecurity function, under which all this pouring and filtering is happening, is specified in Section 8A (‘Information assurance and cybersecurity’) of the Bill/Act:

8A Information assurance and cybersecurity

This function of the Bureau is—

“(a) to co-operate with, and provide advice and assistance to, any public authority whether in New Zealand or overseas, or to any other entity authorised by the Minister, on any matters relating to the protection, security, and integrity of—

“(i) communications, including those that are processed, stored, or communicated in or through information infrastructures; and

“(ii) information infrastructures of importance to the Government of New Zealand; and

“(b) without limiting paragraph (a), to do everything that is necessary or desirable to protect the security and integrity of the communications and information infrastructures referred to in paragraph (a), including identifying and responding to threats or potential threats to those communications and information infrastructures; and

“(c) to report on anything done under paragraphs (a) and (b) and provide any intelligence gathered as a result and any analysis of the intelligence to—

“(i) the Minister; and

“(ii) any person or office holder (whether in New Zealand or overseas) authorised by the Minister to receive the report or intelligence.

Section 8A(a)(ii) is interesting. Any “information infrastructures of importance to the Government of New Zealand” can be surveilled (i.e., ‘filtered’, ‘sifted’, ‘sieved’) to ensure “the protection, security, and integrity of … communications, including those that are processed, stored, or communicated in or through information infrastructures“.

Stored? So that is where the water goes when it passes through the filter – into a big bucket called an information infrastructure ready, I guess, to be ‘filtered’ again some other day? Strangely enough, John Key didn’t mention where the water went once it passed through the filter. Does water ‘evaporate’ in cyberspace, I wonder? Ever?

The ‘filter’, of course, does not need to store the water because it’s already being conveniently stored by the ‘information infrastructure’ which can be accessed whenever the Prime Minister and a retired judge can be convinced that it might be useful for ‘national security’, ‘New Zealand’s wellbeing’ or ‘New Zealand’s economic wellbeing’ – hardly ever, then, I guess.

What seems to have been completely overlooked – at least by the relevant Minister – is that the metadata (and more) is already being stored – the GCSB now just have the legal right to access the storehouses, filters at the ready. I guess it’s sort of like the ‘contracting out’ of the storage functions of the GCSB – quite in keeping with modern public sector ideology.

Not ‘wholesale spying’ then? Not ‘mass surveillance’?

The whole argument about ‘wholesale spying’ was, in the Campbell Live interview, spun by the Prime Minister as being laughable by virtue of the fact that he was given an estimate (by whom?) that it would take 130,000 people and $6.6bn to listen to every telephone call and read every text message in New Zealand.

Putting aside the question of why the Prime Minister, prior to a television interview, would have asked someone to come up with that estimate, it betrays a rather endearing, old-fashioned interpretation of what it would take to undertake ‘wholesale spying’.

Apparently, we are no longer in the realms of pure ‘SigInt’ (signals intelligence) with its hi-tech inspection of streaming data. Instead, in John Key’s understanding, we are back in the days of individual spies (‘HumInt’) listening in, no doubt with headsets permanently glued to their ears and eyes glued to the screen in front of them.

But, surely, things have gone a bit beyond that in the world of cyber-spying? And, with the new power to operate under an ‘access authorisation’ (not a more targeted ‘interception warrant’), surely the expectation is that the GCSB will not be ‘filtering’ electronic communications purely through human ears and eyes?

Which raises the final question.

How can any of us know what ‘capacities’ the GCSB now brings to domestic spying given that, presumably, it is a national security risk (or risk to our wellbeing, economic or otherwise) to divulge its technologies and methods?

It was telling in the Campbell Live interview with John Key that the moment specific technologies and methods were raised by John Campbell, the Prime Minister adopted a neither confirm nor deny response – oh, and a transport metaphor:

It doesn’t matter if I got here in a bus, I came here in a taxi, or I came here in a crown car. What matters is I got here. It doesn’t matter what techniques GCSB use, or don’t use. What matters is it’s legal.

Well, for a start, the techniques the GCSB use presumably matters to whomever the people were who gave Key his ‘estimate’ of the people and money needed to carry out ‘wholesale spying’. [As an aside, hopefully the Prime Minister wasn’t divulging to us, in that comment, the techniques the GCSB use to surveil our communications?]

Further, when it comes to reassuring New Zealanders that they are not being subject to ‘wholesale spying’ it is hard to see how that argument – for or against – can be put without reference to the means of surveillance. (And the point about it being ‘legal’, by the way, is neither here nor there. At issue is, in fact, that suspicion that the Act does indeed make wholesale spying’ legal.).

To use John Key’s transport metaphor, it is relevant how he got to the interview, for a whole host of imaginable reasons. If the point at issue was the Prime Minister’s carbon footprint what is actually irrelevant to that issue is ‘that he got there’.

Similarly with the GCSB. The point at issue is not that the Bureau ends up getting some particular information legally. It is whether or not, in ‘getting there’ they employed techniques that involved ‘wholesale spying’.

If, for instance, the GCSB can use techniques already honed and primed (perhaps through their use by overseas intelligence agencies) to ‘filter’ massive data flows in ‘real time’ and massive data bases in an instant (and without needing to hire 130,000 individuals or spend $6.6bn) that increases the credibility of the charge that ‘wholesale spying’ has been facilitated. If patterns of keystrokes can be identified from months or years of stored digital fingerprints or simultaneous communications then, surely, that also bears on the question of the capacity for ‘wholesale spying’?

In the novel ‘1984‘ the protagonist, Winston Smith, lived in a world with CCTV in every private room and public place – even in the bedroom where he would rendez-vous with Julia. Today, CCTV is in many shops, in public places, on public transportation and on roads and intersections. The signs in those places explicitly remind us that we are ‘under surveillance’.

Yet, of course, there is not always someone sitting watching the screens in ‘real time’. But what happens when the Police are in search of a suspect or want to track the movements of a missing person? The videos from the cameras are viewed, ‘filtered’ for information of use.

Further, we may not have CCTV cameras installed by the state in our private homes but we do have our computers, our telephones and our mobile phones and smart phones (the latter, often registering our locations). And some of those devices hardly ever leave our sides [In fact, in the US there’s been something of a furore over school IT departments snapping 66,000 webcam shots, remotely activated, that were in possession of school students who had taken them home.)

Marshall McLuhan famously said ‘the medium is the message’. There’s a sense, too, in which the technology is the spying. Which brings me to an answer to the question of whether or not we now live, in New Zealand, with 100% pure surveillance. And, if so, in what sense?

100% Pure Surveillance?

Whatever the claims made in defence of the GCSB legislation – and the need for it – the truth is quite clear: We have taken another large step towards normalising the idea that security trumps freedom.

In considering the consequences of that shift, it’s hard not to think of Orwell’s ‘1984‘. In fact, I’ve already made reference to it. But, is that an over-reaction?

Here’s a quote from that most quotable of novels:

“You had to live—did live, from habit that became instinct—in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.”

Irrespective of the assent of the GCSB Act, this assumption is now being made by more and more New Zealanders and by more and more citizens of many countries around the world. We all now tell each other the advice that ’emails are like postcards’ and know now that our Facebook accounts and bank transactions can rightfully be accessed by our employers.

So, I think we can put a big tick next to that quote.

And another;

Now I will tell you the answer to my question. It is this. The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power, pure power.

…

We know that no one ever seizes power with the intention of relinquishing it. Power is not a means; it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship. The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power.

And the object of surveillance is surveillance. And surveillance is not a means; it is an end.

So the intention is, after all, 100% pure surveillance.

Pingback: GPJA #477: Anti TICS Bill public meeting in Wellington September 23 | GPJA's Blog

Pingback: GPJA #477: Anti TICS Bill public meeting in Wellington September 23 « LiveNews.co.nz

In reading your well thought-out and executed article I am instantly taken back to Naomi Wolfe’s book ‘The End Of America: A Letter Of Warning To A Young Patriot’, in which she discusses the basics steps put into placed by up-and-coming wannabe dictators, of which mass-surveillance systems being applied is one such step, and how these ten basic steps had been set into place in America during the second Bush administration.

An avid news-watcher I have become increasingly alarmed at the application of exactly these same steps here throughout the Key administration, but further, that such steps are being set into place in various countries about the globe simultaneously. History shows repeatedly that this basic ten step program is used to subvert civil rights and has been utilised to usurp power over & over again, and, if for this reason alone, the GCSB Bill should be abolished or at the very least circumscribed in order to avoid such potential for it’s abuse. If we don’t want to face the possibility of a future NZ dictator we should first ensure that we do not institute such legislation as would make it simple for authoritarianism to take hold.

Hi Mark,

Thanks for commenting. The book sounds like one I should read.

I remain unconvinced that what is, in effect, the normalisation of pervasive surveillance is a price we must pay for security from ‘cyber-threats’ or, frankly, the supposed direct threat of terrorist events occurring in New Zealand.

As a nation we are always under threat of being pressured into wars by our allies which are often based on very dubious grounds and quite directly result in the deaths of New Zealanders.

It just doesn’t make sense to set up a surveillance system so suited to monitoring individuals, groups and, under some circumstances, a large proportion of the population’s communications.

Thanks again for the thoughtful comment.

Regards

Puddleglum