There’s an aspect of the political polls that I suspect many people are unaware of.

As percentage support for each party is reported, most people probably assume that more people are supporting the parties that show an increase in percent support and fewer people are supporting those that show a decrease.

It’s not quite that straightforward.

As ‘swordfish’ has emphasised in some posts on the blog ‘Sub-Zero Politics‘ (in-between amazing photos of Norway and the Faroe Islands), if you ignore the undecideds you can get a very misleading picture of the state of the political mind of the electorate.

Looking back over the last two years of Fairfax/Ipsos polling with due consideration given to the undecided voters there’s some interesting insights to be had into that mind.

Those insights also raise questions about how poll results are being reported and why they’re being reported in the way they are.

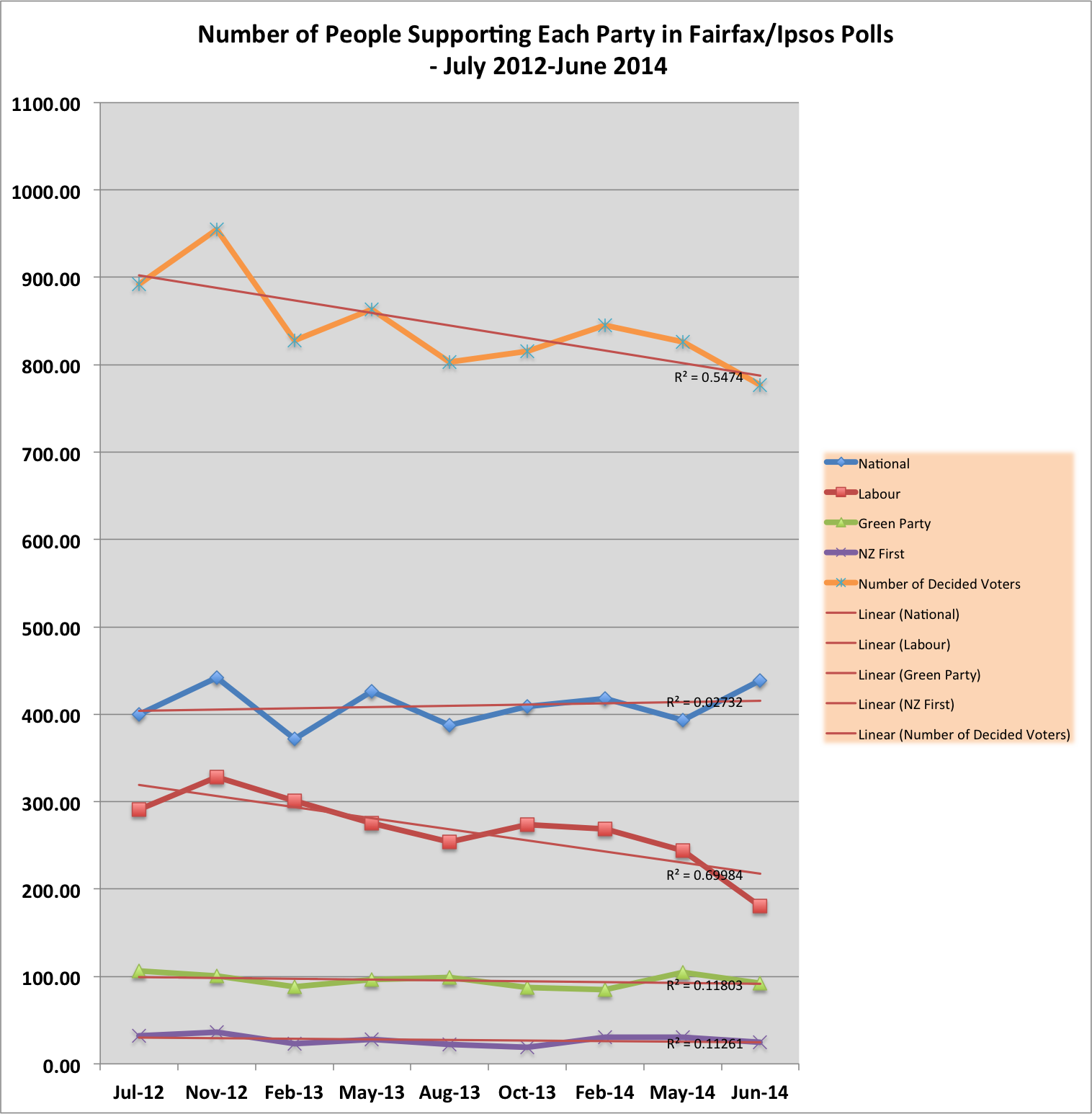

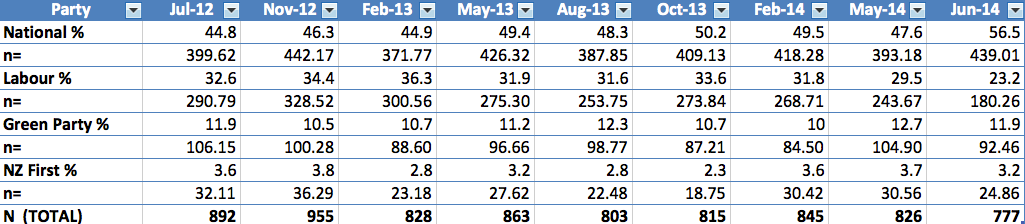

Below is a graph (and corresponding table) of party support over the last two years of Fairfax/Ipsos political polls expressed as the actual number of people per poll who affirmed support for the four main political parties.

There’s a few interesting points to make about this graph. There’s a couple of things to remember, though, before making those points.

- Each poll sampled roughly 1,000 people (usually marginally over). Avowed support for each party can therefore be expressed as a percentage of (roughly) a random sample of one thousand people. The Green Party, for example, is supported by just under or just over 100 people per poll. Avowed support per 1,000 New Zealanders is therefore 10.0% of the adult population.

- For now, I’ll ignore all the debates over polling methodology (e.g., landlines versus cellphones, who is more likely to answer phones or agree to participate, etc.). I’ll assume, that is, that the (roughly) 1,000 people sampled in each poll is a truly random sample.

Given those two points, what does the graph show?

First – and perhaps most surprising for many people who’ve read the headlines about these polls – the number of people in a sample of 1,000 adult New Zealanders who express support for the National Party has hardly changed over the past two years.

The greatest number of people out of the polling samples over that time who expressed support for National was 442 in November 2012. The smallest number was 372 in February 2013. That’s a range of 70 people over the two years – or about 7% of the 1,000 voter sample.

If you look at the trend line for the National Party (the thinner, reddish line running through the blue National Party polling line) it shows a very small incline from left to right (for the statistically inclined, the R² value is 0.02723, very low). It’s about the equivalent of adding something less than 10 voters out of 1,000 – or 1% of the sample.

Further, the largest number of people avowing support for National was in the November 2012 poll at 442 (out of the roughly 1,000 polled). That’s 44.2% of adult New Zealanders. The percentage party support reported in the poll – based on only the preferences of the ‘decided’ voters who were likely to vote – was 46.3%.

The latest poll, however, has a reported percentage support for National of 56.5%. The number of actual people in that poll who avowed support for the National Party was 439 – three fewer people than in the November 2012 poll.

So, the reported support for National between November 2012 and June 2014 appears to show a 10% increase in the proportion of New Zealanders supporting the party. Yet, there are (marginally) fewer people declaring their support for National in June 2014.

Put bluntly, National has pretty much no more support amongst New Zealanders now than it did two years ago. National is not, that is, ‘running away’ in terms of popularity. Its avowed support has barely shifted, if at all. Any headlines that speak of National ‘surging’ in the Fairfax polls or ‘increased support’ for National are therefore quite misleading.

While National’s solid but stagnant level of support might be initially surprising it shouldn’t be. The National Party vote in the 2011 election was, in absolute votes, only marginally greater than it had been in 2008. It gained 1,058,636 party votes in 2011 and 1,053,398 in 2008. That’s a total increase of 5,238 votes over a period when the total number of registered voters increased by 80,088 electors.

Second – The Green Party support, as mentioned, has also been pretty steady. As with National Party support, those avowing to support the Green Party has varied within a reasonably narrow range (though, at lower overall support, that variation does matter perhaps more for the Green Party than for National).

The number of people expressing support for the Green Party has ranged between 106 (in July 2012) to 84/85 in February 2014. (The trend line has a R² of 0.11803). The range is the equivalent of 21 people or 2.1% of the 1,000 sample size.

For both National and the Green Party it seems that the voting base remains committed and entrenched. (It’s beyond the scope of this post, but the reason for the similarly steady polling may be that the demographics overlap or commitment is more ideological for these groups – and ideology is hard to shift.)

Putting aside questions about the proportion of ‘swapping’ between parties occurring in the population, the nett effect is a reasonably constant appeal.

Third – The stand-out ‘story’ in the graph (and table) is the decline in the number of decided in the polls. The trend line for the decided vote shows a decline over the two years of almost exactly 100 people (and an R² of 0.5474). Put another way, there has been a significant increase of about 100 people in the 1,000 voter sample who are undecided who to vote for or are unlikely to vote.

To an extent that trend line is affected by the very low number of decided voters in the latest Fairfax poll, but some noticeable decline exists irrespective of that poll.

The ‘story’ of the increased number of undecided voter leads to the fourth point.

Fourth – The number of people (in the Fairfax polls) who have avowed support for the Labour Party over the last two years has declined steadily. The trend line shows a drop of about 100 people over that time – pretty much identical to the increase in the undecided vote.

The variation in support is large, mainly due to the latest poll. Labour had a high of 329 people declaring their support in November 2012 and a low of 180 in June 2014. That’s a range of 149 voters. When the latest poll is not included the range is from 244 to 329, or 85 voters. That’s a slightly higher range than for the National Party voter support.

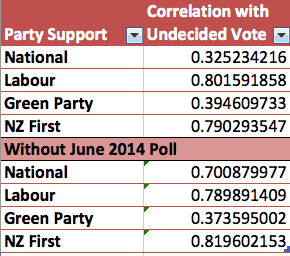

Even before the latest poll is included the Labour Party’s avowed support is more highly correlated with the proportion of the decided vote than is the National Party support. I’ve made a table of the correlation coefficients of each party’s support over the two years and the number of decided voters in each sample.

Correlation of Party Support with Decided voters in Fairfax Polls – July 2012 to June 2014 and July 2012 to May 2014

Over all the polls (the top half of the table) the Labour and NZ First support is highly correlated with the level of the decided vote. That is, the higher the decided vote the higher the number of people declaring support for these parties. Both National and the Green Party – while still positively correlated with the number of decided voters – show a lower correlation.

Basically, that means that for National and the Green Party supporters, as already noted, have a greater tendency to be ‘entrenched’ in their decision at least at the population level. Fewer of their supporters appear to switch from support to ‘undecided’.

For Labour and New Zealand First the story is different. Their support has a greater tendency to switch to ‘undecided’ (or to be less likely to vote).

When the latest poll is not included in the correlation, however, National’s level of support shows closer correlation to the level of the decided vote (the correlation coefficient goes from 0.325234216 to 0.700879977) but still less than the correlation for Labour and New Zealand First support. But it’s important to remember that, while correlated with the decided vote, the actual fluctuation is greater for Labour and New Zealand First than for National.

The major change in the correlation coefficient for National between inclusion and non-inclusion of the latest poll reflects the fact that the National Party support increased (from 393 to 439) while the number of decided voters decreased from 826 to 777.

Even without the latest poll included the Green Party, interestingly, still has a relatively low – though positive – correlation with the level of the decided vote.

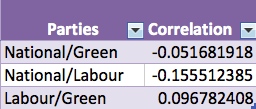

There’s a further correlation that adds some insight into what’s going on. Below is a table of between party correlations.

All correlations are small. The ‘largest’ is a negative correlation between the National and Labour Party support. (Negative means that as one party’s support goes up the other party’s support goes down.) It’s also interesting that the relationship between support for Labour and the Green Party is practically non-existent in the Fairfax polls. (Interestingly, when the latest poll is removed from the calculation of the correlation between Labour and National there is a positive correlation between the support for the two with a correlation coefficient of 0.391170648. That is, when National’s support goes up, so does Labour’s.)

The main ‘story’, from the Fairfax polls at least, is a story of the relationship between Labour Party support and the level of ‘undecided’ vote. That is, when the avowed Labour Party vote goes down so does the level of decision in the electorate overall.

Conclusion

Polls, including the Fairfax polls, headline the percentages for the declared voter support. Without taking into account the level of the undecided vote this presents a misleading picture of how many voting age New Zealanders support each party.

Of course, by limiting reporting only to those who have declared party support and are likely to vote the reporting may very well reflect what could happen in an election.

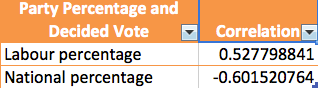

With that point in mind, here’s perhaps the most revealing correlation between the ‘headline’, reported voter support and the level of the decided vote in the Fairfax polls:

[Without the June 2014 poll result, the correlations are: Labour 0.259225079; National -0.416534116. That is, still a positive correlation, though lower, for Labour and still a negative correlation, though slightly lower, for National.]

There’s a very clear story in these two correlations: Put simply, as the decided vote goes up so does the reported percentage vote for the Labour Party.

Conversely, as the decided vote goes up, the reported percentage vote for the National party tends to go down.

The closer the election draws the more likely it is that people will make a decision.

But then there’s one more step – getting people to put that decision into action and actually vote.

Pingback: Herald on Sunday on Labour | Kiwiblog

That trend of lower vote = conservative good news has been studied worldwide. So ask everyone you know – Is it smart to vote?

http://minimalistmum.blogspot.co.nz/2014/06/is-it-smart-to-vote.html

Pingback: Undecided? | Stats Chat

Really, really good stuff. Keep it up.

Hi Ben,

Thanks for the encouragement Ben. I always enjoy getting feedback – good and bad 🙂

Regards,

Puddleglum

Statistics, damn statistic and lies

Hi jo,

That’s an interesting take on an old saying!

Thanks for commenting.

Regards,

Puddleglum

What’s your margin of error for the two conclusions?

Based on his NINE FUCKING DP, this political ‘scientist’ is certain to within 1 part per billion which is impressive given a population of 4 million.

Hi SpoogeCoffer,

Thanks for your assertive comment.

You’re quite right that nine data points is no basis for a prediction about what would happen with a turnout of ‘X’ percent at the election. My point, though, was about the ‘story’ in the Fairfax polls that I thought was not being considered (see my reply to Kmccready).

Given that the stories we do hear from those polls – in Fairfax media – are based on a similarly constrained data set I guess I don’t feel the need to apologise for putting forward the data for this ‘story’.

You’re also quite right about the number of decimal places in the correlations and R squared statistics. Pure laziness on my part – I just used the output from Excel and didn’t bother to round it to two (or three) decimal places. Perhaps if you did the rounding in your head you could counter my laziness.

Thanks again for taking the time to comment.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Hi kmccready,

Thanks for the question.

By the ‘two conclusions’ I guess you mean Labour support going up as ‘decided’ goes up and National’s support going down as ‘decided’ goes up? That is:

“There’s a very clear story in these two correlations: Put simply, as the decided vote goes up so does the reported percentage vote for the Labour Party.

Conversely, as the decided vote goes up, the reported percentage vote for the National party tends to go down.”

If so, then I don’t think it’s appropriate to talk about a ‘margin of error’. Those conclusions just re-state the basic logic of a correlation (as applied to this context).

A correlation is just a statistic that describes the relationship between two ‘variables’. It isn’t predictive or inferential, it just describes – and summarises – the data set it’s applied to. And, as I said in the post, I assumed that the polls represented pretty much perfect random samples of the electorate so I was ignoring any measurement error.

In other words the two conclusions are conclusions about the data in the Fairfax poll, not about a prediction as to what might happen if, say, voter turnout (a final ‘proxy’ for ‘decided’ voters in the polls) was at a certain level (75%, 80% or whatever).

The point of the post was that, in those polls, the ‘real story’ (or the unnoticed but interesting story) was (a) that the number of people per poll who avowed support for National has been pretty constant over the two years, which a focus on reported percentages doesn’t reveal, and (b) the number of people who avowed support for Labour declined in a way that was correlated with the steady decline in the number of people who had made a decision over party support in successive polls.

It does suggest what might happen if we assume that the correlation in the poll data carry’s over into actual voting behaviour. But, statistically, that doesn’t follow from a correlation. Correlations provide a basis for prediction but aren’t themselves predictive.

What would be needed to provide a statistically valid prediction about the relationship between ‘decided vote’ and the Labour and National Party percentage vote in the election would, at the least, be a linear regression equation based on as much polling data as it would be possible to collect. (The line of best fit may not even be linear.)

In that case, it would be also be possible to calculate a reliable measure of “the proportionate reduction of error in predicting Y [i.e., any dependent variable] relative to simply guessing the mean of Y.” (from a stats text). That statistic is r squared (‘r’ being the correlation coefficient).

Of course the analysis in this post was based solely on nine Fairfax/Ipsos polls and that’s hardly a large sample. Partly because of that I didn’t bother calculating a linear regression equation.

Fortunately for me, Thomas Lumley, Professor in Statistics at the University of Auckland had a go at that on the blog ‘Stats Chat‘. He’s done a perfectly reasonable critique of the stats in my post – though seemed to think I was trying to make predictions rather than (very simply) summarise Fairfax polling data.

Anyway, from doing a series of linear regressions Professor Lumley found that:

“When I do a set of linear regressions, I estimate that changes in the Undecided vote over the past couple of years have split approximately 70:20:3.5:6.5 between Labour:National:Greens:NZFirst.”

And,

“The data provide weak evidence that Labour has lost support to ‘Undecided’ rather than to National over the past couple of years, which should be encouraging to them. In the current form, the data don’t really provide any evidence for extrapolation to the election.”

Having said all of that, there’s plenty of empirical support for the finding that socio-economic and educational status are significantly correlated with voter turnout. And it’s reasonably uncontroversial that the Labour Party has disproportionate support from the demographic with low socioeconomic and educational status.

I hope that helps answer your question – at least partly.

Regards,

Puddleglum

I found the very interesting stat to me in the latest Fairfax poll that got little media interest was the fact that 46 % of the people polled wanted a change of government. That’s a stat that will have National very worried. I also wonder how truthful people are about answering their political allegiance to a random phone caller. I think to most that’s something they actually don’t want to reveal.

Hi John,

Yes, that’s an interesting one. The blogger ‘swordfish’ on the blog I linked to in the post has done a great job of explaining the ‘change of government’ statistic. It was that explanation that got me interested in looking a bit more closely at the Fairfax polls.

As for the truthfulness of people in answering polls, that’s been pretty exhaustively examined and, so far as I understand it, the consensus seems to be that people’s responses are honest enough most of the time so as not to threaten the overall validity of a poll (of course, other methodological issues may be a problem).

My interest is partly in what it actually means when someone gives a (genuine) answer. What led to the answer being given? How much did it depend upon ‘situational’ factors, recent media events, etc. and to what extent are the responses about ‘sending messages’ (to politicians, political parties or to other New Zealanders) rather than providing a first-hand estimate of their own likely behaviour?

Thanks for taking the time to comment. Much appreciated.

Regards,

Puddleglum

A very interesting read, thank you. If only journalists had (a) a grasp of statistics and (b) a modicum more integrity, things would be far more informative.

Brilliant work Puddleglum! Thank you. This is the most sensible thing I have read all week, and it deserves a wide audience. You may have noticed your website traffic spike up in recent days I hope?

Pingback: Undecided? | Kiwi Poll Guy

I have a couple of questions / comments on the above data.

Firstly, if I am reading this correctly, it seems that Fairfax/Ipsos are reporting their numbers as percentages of people who have declared for a particular party, and not as percentages of the total sample size. This seems a little misleading to me. I have to question their motivation for presenting their data in this way. Aren’t undecideds a valid proportion of the population, and doesn’t the percentage of undecideds reflect in some way the public perception of the current political landscape? Doesn’t this mean then that instead of the reported 56.5% (439/777*100) support for National recently, that their true figure is actually around 44% (439/1000*100)?

Secondly, in the table above how come the number deciding for each party isn’t a whole number? This can’t be the raw data, it isn’t possible for 180.26 people to be supporting Labour in June 2014 for example.

Interesting stuff.

Cheers,

Lats.

Hi Lats,

Yes, like most polling media outlets Fairfax report party support percentages as a percent of those who’ve declared party support and not out of the total sample. The rationale for that is the notion that those who are undecided or who say they are not likely to vote are also perhaps unlikely to cast a vote in the election.

The fractions of a person (obviously impossible) come from rounding of the percentages reported by Fairfax on their interactive graphic (which is where I got the figures from – you hover the cursor over the data points on the party graphs and the ‘decided’ sample size and percentage support appear.) I left the raw calculation in rather than rounding it myself.

Thanks for the comment.

Regards

Puddleglum

Thanks for the clarification Puddleglum. It had never occurred to me up until now that opinion polls may be being reported in this way. I understand the rationale, but it does feel a little misleading to me to be reporting popular support for the Nats at above 55% when in fact the true figure is closer to 44%. I grok that this is an estimate of number of people likely to vote, and understand why undecideds are excluded, but it still doesn’t sit comfortably with my OCD ways.

Of course this also drops Labour’s support down to an astonishingly low 18%. This must be worrying for Labour insiders. I’m generally left-leaning myself, so am saddened by the apparent demise of Labour, but their figures can’t be seen in isolation in an MMP environment. One has to remember that the left has splintered much more than the right, and any left-aligned government is going to be a coalition of Labour, the Greens, with possible support from a host of smaller parties including Maori, Internet-Mana, United Future, and NZ First.

National, on the other hand, is sitting virtually alone on the right, any support parties are likely to contribute only one or two MPs each. ACT is essentially dead now, and only another Epsom cup of tea deal will see them survive. Craig’s Conservatives may save the day for the Nats, but again a cup of tea will likely be required. And in spite of Key’s and Craig’s denials you can bet your bottom dollar that this will happen. Peter Dunne is essentially a centrist and could realistically work with either National or Labour. Similarly NZ First could theoretically work with either, but I get the feeling that Peters and Key don’t like each other much; there are some pretty big egos butting heads there, so it may be a difficult relationship to maintain.

The Maori Party surprised a lot of people when they cozied up to the Nats and I still think that at their heart they’d feel a lot more comfortable working with the left. Kudos to them for being pragmatic though, they realised that the only way they could achieve anything for Maori was to be part of Govt. They’d have been a voice in the wilderness if they’d been sitting on the cross benches.

All in all, and despite the recent poll results, it is shaping up to be a very interesting election this year.

Hi Lats,

I agree that presenting people with the notion that over half of their compatriots support National is misleading. It especially concerns me given that humans have a strong streak of conformity in avowed opinions and behaviour. That’s especially true when it comes to matters that someone has not thought about a lot or has little motivation to think about.

There’s good evolutionary sense to that ‘conformity’ in opinion and behaviour of course. As Pinker notes in his book ‘Better Angels’, it makes sense over many issues to take the lead from what others believe is best – a common view or course of action is more likely to be adaptive than even the workings of the mind of a sole genius.

But when information about the ‘common view’ is a bit skewed and when we’re dealing with very modern electoral processes like MMP, there’s no guarantee that going with what one takes to be the majority view will be best.

And your point about the ‘fragmentation’ (or, just, diversity) of options on the left is also interesting. When there’s really only one option (National or nothing, so to speak) you’re likely to stick with it for the long haul; when there’s more than one viable choice then maybe it makes sense to keep your mind open for as long as possible (e.g., until you walk into a booth) especially if your ‘first choice’ is looking a bit shabby.

The problem – or unintended consequence – of that might be that the poll results start to exert their own effect on that ‘spoilt for choice’ response of being ‘undecided’.

Not voting can then become a distinct ‘best’ option, of course.

Regards,

Puddleglum

Pingback: Undecided voters and political polls | Grumpollie

Pingback: Polls and undecideds | Your NZ

Thanks for the alternative poll reading which gives me more hope we may see a change of government. In “Ill fares the land” Tony Judt expresses surprise that there hasn’t been more of an outcry from voters as right wing governments like National roll back the social institutions that have formed the basis of our decent society.

I’d be the first person to admit I have no idea whatsoever about statistics, and mathematics in general is a bit of an arcane science to me. What I would like to find out (in very simple, laymen’s terms) is this – how accurately do these opinion polls predict what happens on election day? Is there any correlation between what Colmar Brunton or Fairfax report with these polls to the election outcome? I personally think that far too much importance is placed on polling – after all, the only poll that actually matters is the one on the day of the election – but I am curious to find out if there is any correlation to these polls and the outcome.